Amanda Adams (8 page)

Authors: Ladies of the Field: Early Women Archaeologists,Their Search for Adventure

Tags: #BIO022000

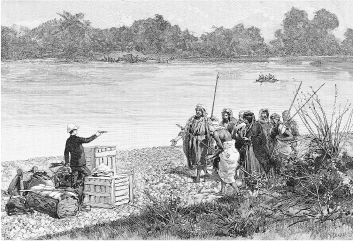

ABOVE :

Jane Dieulafoy protecting her crates of precious artifacts against theft

ANOTHER, MORE EXTENDED

return to France was inevitable and probably even anticipated with some relief. The Dieulafoys returned as archaeological celebrities, and the sum of all their fieldwork could now be written up and published. Both of them were also wracked by fever, and a hot bath must have been a blessing. They had amassed four hundred crates of archaeological material (forty-five tons in weight

22

), all of which would be delivered straight to Paris via ship and rail. The Lion Frieze would eventually make its way unharmed to the Louvre too.

During her time at Susa, Dieulafoy wore men’s clothes exclusively. A photo taken of her while in the field shows a woman who, no matter how carefully one scrutinizes the picture, looks just like a man.

23

She sits on a small cot, large umbrella in the corner, facing the two men in her company. Her legs are parted, not crossed, and she’s resting her cheek in her hand, a pose that is tough and shows her ease in a field camp. She looks impatient, likely because the rain is pouring outside and keeping her from her work. Her outfit is the daily standard: black leather boots, dark pants that appear thick and heavy like wool, a man’s shirt buttoned up to the neck, and a man’s overcoat, no collar, buttons down the front, cuffs turned. Her hair is short as a schoolboy’s and she sports a plain black hat on her head. Coffee cups are strewn about, and at her feet are a number of kettles and containers, each hand-drawn in the photo and touched up with what looks like dabs of whiteout and blue ink. Piles of saddles, field gear, blankets, and boxes surround Dieulafoy and her companions. One of the fellows is smoking a hookah in the corner; the other, with very short dark hair, black eyes, and a mustache, is looking away absently. Rugs are spread on the ground and hay beneath that. A thin tree trunk in the center holds the tent up, and its fabric radiates behind Dieulafoy in a sweeping fan of vertical lines that evoke just a hint of circus tent. She is clearly in her element.

Upon her return to Paris, Dieulafoy publicly forsook women’s clothing completely and forever. She explained her decision to dress in masculine attire as something she did for comfort and practicality: “I only do this to save time. I buy ready-made suits and I can use the time saved this way to do more work.”

24

But surely, she was also aware of its effect and must have enjoyed the sensation she created.

For Dieulafoy, wearing men’s clothes was not the equivalent of wearing sweats or her husband’s sweater around the house (or the site). She wore up-to-the-minute Parisian men’s fashion for all it was worth. Jane Dieulafoy was a genuine cross-dresser. While an overcoat had afforded her disguise as a boy during the Franco-Prussian War, her dress now had nothing to do with deception or safety; rather, it was a bold and personal statement. She even had to get police permission to dress as she did.

The New

York Times

reported on the illustrious Madame Dieulafoy, who, “having become accustomed to wearing man’s clothing during her travels, received the authorization of the Government to appear in public in the costume.”

25

This privilege was normally reserved only for the ill or handicapped.

It was a personal statement, but what kind? Beyond comfort and “practicality,” was there another meaning? Some have ventured that Dieulafoy was a lesbian, a nineteenth-century butch of sorts. Yet her love for and partnership with Marcel was very profound and seemingly romantic too. There is no evidence that she was ever with other women. And quite at odds with the notion of lesbianism at the time, Dieulafoy was extremely conservative. She was also stringently opposed to divorce and believed that a woman’s true place was beside her

man.

As equals, yes, but Dieulafoy believed that a woman’s greatest worth was to be found not through independence but through partnership— found in a husband. The scholar Margot Irvine invites us to consider the scene in which Dieulafoy sharply reprimands a twenty-eight-year-old journalist who is bored by her husband, craving adventure, and considering leaving her marriage: “Divorce works against women, it annihilates them, it lowers their status, it takes away their prestige and their honor. I am the enemy of divorce.”

26

She made the young woman cry, yet when she left the girl had “tears running down her cheeks but her face was beaming.”

27

Dieulafoy offered a little more explanation, remarking, “I only wish to show that happiness comes from doing your duty towards others and not from satisfying your wishes and whims. The best way to love your husband is to love his soul, his intelligence and also the highest expression of himself, namely his work in the world.”

28

While some of the first women archaeologists found freedom roaming deserts and sailing away from the rules and rigmarole of Victorian society, Dieulafoy found freedom through marriage. It was as a wife that she released herself from consuming concern for her own wants and needs and latched onto something bigger. Through her version of selflessness, Jane found liberation. The young journalist “beaming” with tears in her eyes apparently saw the potential for the same.

As a couple the Dieulafoys were admired and teased. The manly Jane cut an eccentric profile, and jokes about “who wears the pants” in the Dieulafoy household were the stuff of comics galore. But they carried on unabashed about their boldly different marriage—or at least their

style

of marriage, in which man and woman both wore the pants. Both were famous in their own right: Marcel increasingly so as an archaeologist, and Jane not only as France’s first popularly known woman archaeologist but also as a writer, photographer, essayist, and all-around literary figure. Their installations of Susa’s artifacts and monuments at the Louvre brought them into the public spotlight, and crowds flocked to see the new Persian galleries.

Meanwhile, both Dieulafoys reaped rewards for their contributions to archaeology (and for bringing added prestige to France’s museums); Dieulafoy was one of the very few women awarded a cross from the Legion of Honor. Between the two of them, distinctions between male and female were fluid, seamless, even elastic. They considered themselves a unified whole, and as Dieulafoy once began a speech, “When addressing the moon, one hesitates to use the masculine or the feminine form.” Jane and Marcel were the Dieulafoy moon.

THE

DIEULAFOYS’

PASSION

for Susa was stronger than ever, and they were anxious to return. Unfortunately, negotiations with the Persian authorities had come to a crawl. As troubles mounted and their return looked more and more difficult, Dieulafoy gave vent to her anger in a letter to the government in which she “dared to express her feelings regarding the political and social state of Persia and the way its sovereign ruled.”

29

It was something no official wanted to hear, especially from the mouth of a woman. Some even suspect that the government withheld support precisely because of her gender. One scholar notes that another “one of the reasons the Dieulafoys weren’t able to return to Susa was due to Jane Dieulafoy’s involvement in the mission. It clearly went beyond what was expected of a dutiful wife at the time and other scholars were uncomfortable with her very active role.”

30

In any event, the shah of Persia was offended. Dieulafoy had gone too far.

As Jane and Marcel waited for permission to continue their archaeological exploration of Susa, a man named Jacques de Morgan landed on the soil they loved so much. He traveled through the country from 1889 to 1891 and began to overshadow the Dieulafoys. Ultimately, he became director of the French Archaeological Delegation in Persia as the Dieulafoys sat wringing their hands in Paris. Susa became his. It was a stinging loss.

Persia was thus relegated to a dream and shared memories. As the years passed and they became further removed from the part of the world they loved best, Susa morphed into a phantom of inspiration. Dieulafoy wrote her first novel,

Parysatis,

with the ancient site as its backdrop. The book was filled with reconstructions of the ancient city—the palace walls and courts, monuments, and people were returned to vibrant life through her careful reconstructions of time and place. It later became a famous opera. Dieulafoy began to shine as a woman of literary stature and just as she had once seized the pickaxe in service of archaeology, she now took up the pen and made writing her cause. She fought alongside other prominent women authors of the day to open the gates of France’s Académie and let the ladies in.

The work of highly regarded female authors was consistently denied recognition by French literary awards. In response, Dieulafoy and several other women, including Juliette Adam, Julia Daudet, Lucie Félix-Faure Goyau, Arvède Barine, and Pierre de Coulevain (many women writers used pseudonyms to publish at the time) came together in

1904

and helped to establish the Prix Femina. This new award helped to transform the face of French literature. The prize could go to either a man or a woman, but the jury was—and is to this day—exclusively female. Dieulafoy sat on the first jury. Even without Susa in reach, she was a celebrity in Paris.

Archaeology was still in the Dieulafoys’ blood, however, and having lost Susa, the two set their sights elsewhere. Marcel’s knack for archaeology revolved around making connections. Just as he had once sought the origin of medieval Western architecture in Asia, he now opened his research to include Spain and Portugal. The couple traveled extensively, much as they had on their first expedition through Persia, photographing the old buildings and churches.

Circumstances of war and serendipity also brought them to Morocco, where they hoped to actively excavate again and fuse their theories about how the Orient’s architecture mingled with the West’s. They embarked on excavations of a local mosque, and because Marcel was busy working for the engineering corps (part of what brought them there in the first place), Jane directed the work by herself.

31

Soon they were invited to excavate in other areas and were busy once again in the field.

All of that changed when Dieulafoy contracted amoebic dysentery through the unsanitary food and water on site. She was too weak to work, so the couple returned to France in hopes of renewing her health. She recovered quickly, and they rushed back to Morocco. But sickness struck again. Whatever strength she had regained back home withered away. She and Marcel left for France again and settled in their hometown of Toulouse, ready to see her heal for good. She made it through the following autumn and winter, but died in the spring. She was wrapped in Marcel’s arms when she took her last breath at age sixty-five.

32

A NEWSPAPER ARTICLE

written when Dieulafoy was still alive reflected on the couple’s marriage. Unlike other accounts, which poked fun at their unusual dress, this one celebrated it, noting in almost historic terms how “our time can showcase, for the generations to come, unique examples of great and beautiful households, like those of . . . the Dieulafoys. The wife becomes a collaborator with her husband, sharing the excitement of his work, his moments of enthusiasm and his moments of discouragement . . . What a beautiful sight, indeed.”

33

Most of the women chronicled in this book overcame odds and obstacles to succeed alone in a man’s world. Dieulafoy shows us something different. The partnership between her and Marcel is a shift from feminist narratives that subtly (or stridently) exclude men from the trajectory of a woman’s success. Dieulafoy was in lockstep with her husband, and he with her, and surely someone as trendsetting and smart as Dieulafoy could have achieved much in life with or without a man. Granted, her challenges would have been precipitously steeper if she had been solo, and gaining permission to excavate would have been nearly impossible. Nonetheless, the wives who excavated with their husbands were collaborators in the truest sense, and Dieulafoy received more recognition than most.

ABOVE :

Beloved companions Jane and Marcel Dieulafoy