Amazing Tales for Making Men Out of Boys (18 page)

Read Amazing Tales for Making Men Out of Boys Online

Authors: Neil Oliver

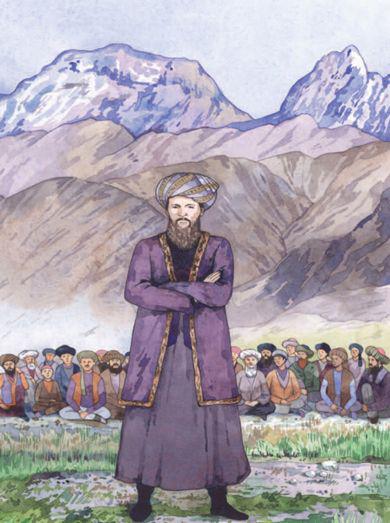

Josiah Harlan, the Man Who Would Be King

“Cut, you buggers—cut!” bellows Daniel Dravot, fearless and defiant to the last, as a priest uses a machete to hack at the mainstays anchoring a rope bridge across a terrifyingly deep ravine. He’s the Man Who Would Be King—King of Kafiristan—and he’s been found out at the last. Having allowed his subjects to believe he’s a god—nothing less than the reincarnated son of Alexander the Great and the rightful ruler of the land—he’s been brought down by the woman he chose to be his queen. Roxanne, beautiful but gullible, believed physical union with a god would cause her to burst into flames. In her terror, she bit his face as he tried to kiss her on their wedding day. As the blood flowed down his cheek, the priests realized Dravot was not a god but a mortal man—and a fraud. After a brief and unsuccessful attempt to flee, accompanied by his best friend Peachy Carnehan, the pair are captured and marched to a ravine marking the boundary of Kafiristan. Carnehan is made to watch while Dravot is forced to march out onto the wooden planking of the bridge. Once he’s in the middle, suspended in space over a drop of thousands of feet, priests on either side cut the ropes and Dravot falls and falls and falls—he falls so far he’s out of sight before he smashes onto the rocks below. This is the end of the man who would be king…or at least, the end imagined by the great English storyteller Rudyard Kipling and turned into a movie by American director John Huston. The fact is that Kipling based his yarn on a real man—a real-life adventurer. And while his leading character was an English soldier called Daniel Dravot who met his maker in the fictional land of Kafiristan, the real man who would be king was a 19th century American Quaker who became Prince of Afghanistan, led his own regiment of Union soldiers during the American Civil War and died, alone and forgotten, on a street in the city of San Francisco.

Josiah Harlan was born on June 12, 1799. He was the ninth child and sixth son born to Joshua and Sarah Harlan, a Quaker couple living in Chester County, Pennsylvania. A seventh son, Edward, would complete the family four years later. Josiah grew to be a tall, strapping lad, self-confident to the point of arrogance. He was passionately interested in botany and medicine, and in Greek and Roman history. A voracious reader, he devoured the contents of every book he could lay his hands on, teaching himself Latin and ancient Greek along the way. He was especially fascinated by the achievements of Alexander the Great—and it was this interest that planted the seed for the adventure that would come to dominate his life.

In early 1820 Josiah’s father arranged for him to serve as the “supercargo”—the commercial manager—aboard a merchant ship bound for China and India. This first trip lasted over a year and the travel bug bit Josiah hard. In 1822, just months after his return home, he set sail aboard another merchant ship bound for the East.

The lands with which young Josiah now began to make contact comprised another world entirely. He took his first taste of that strangeness, that utter foreignness, less than 200 years ago, and yet the places he described are, in large part, as lost to us now as the civilizations of the ancient Greeks, the Aztecs or the Celts. More than anything else—the crucial difference from our 21st century perspective—the unknown world then was a far, far bigger place. In the early 19th century there were still places—many places—where a man who so wished could disappear, could cast off the person he had been before and become something quite new. In 1822, even the America of Harlan’s birth still held sights, sounds and smells as yet unknown to most white inhabitants of the continent; much of the West was still there for the winning, after all. But a white man disembarking from a sailing ship in a port like

Calcutta, in the first decades of the 19th century, encountered wonders, dangers and possibilities too many and varied to be dreamed of today.

Harlan might well merely have skimmed the surface of those shocking, intoxicating, captivating worlds before returning home to a life of domesticity and convention. But while he was still in India he received a letter that would change everything—a letter from his fiancée. They had met back home the year before—during the break between his voyages—and Harlan had quickly fallen in love and proposed marriage. The woman had accepted his offer but, distance having made her heart grow less fond, she’d since met and married another. This then was the stark news she put in her letter to Josiah. Such a missive would have upset any faithful man, but for Harlan it built a wall separating his past from his future. It seems too that between the lines of that letter he glimpsed a truth he had not noticed before: that the distant world of Chester County, Pennsylvania, was a small one. Perhaps it looked to him now, from such a distant viewpoint, too familiar, too claustrophobic and too staid. It was anyway a world much too small.

Accordingly, he turned his back on all he had known before and set about making himself anew. Despite the fact that his only medical knowledge was self-taught from books, he joined the Honourable East India Company in 1824 as a military surgeon. He was part of the subsequent British invasion of Burma before illness overtook him and forced him to step out of the lines and take time to recover. The truth was, however, that he had begun to feel stifled and held back by the formalities and strict hierarchies of that most British of institutions. By 1826 he had resigned his post in favor of exploring the mysterious interior of the great sub-continent.

Already taking shape in his mind was an extraordinary fantasy—a dream rather more believable in the context of a fictional short story than anything normally contemplated in real life: having seen

the British Empire in action, Harlan had begun to plan for nothing less than an empire of his own.

Beyond the vast tracts of India controlled for Britain by the Company lay the darkly exotic territory of the Punjab—still independent and ruled by the Maharajah Ranjit Singh, leader of the Sikhs. Precious little was known about the Punjab; the Maharajah and the Company lived side by side peacefully enough but each tended to mind his own business. But beyond the Punjab, further to the north and west, lay the entirely mysterious Muslim country of Afghanistan. A handful of Westerners had penetrated its borders—if hearsay was anything to go by, at least—but in 1826 next to nothing was known about who lived there, and how.

As a student of Greek history, Harlan knew Afghanistan had once numbered among the conquests of Alexander the Great—but that had been more than 300 years before the birth of Christ. During the intervening 20 or so centuries, a shroud-like curtain had swung into place between that forbidden and forbidding place, and the nations of the West. In the mind of a man like Josiah Harlan—a man who saw no earthly reason to set any boundaries around his ambitions—it seemed the lost world of Afghanistan might be the place in which a fellow could and should make for himself a kingdom. He could follow in the footsteps of Alexander and find space for his own greatness.

In the border town of Ludhiana, beside the Sutlej River marking the boundary between the Punjab and British India, Harlan succeeded in gaining an audience with a dispossessed King of Afghanistan. Shujah Shah Durrani had once sat upon a throne in the fabled city of Kabul, but had been deposed by his half-brother, a man named Dost Mohammed Khan. He lived now in elegant exile in British Ludhiana, brooding darkly about all that had been, and that might be again. Shujah and Dost Mohammed Khan were senior representatives of two rival clans competing endlessly for

power. Dost Mohammed was of the Barakzai, while Shujah was of the Saddozai. But in truth, the whole country was riven by uncountable blood feuds caused by slights real or imagined—family against family, clan against clan—creating a lethal web of Byzantine complexity. Any man seeking to get himself involved in the ebb and flow of power between the clans did so at great peril.

It is therefore very hard to imagine the combination of self-confidence, gall and arrogance required to enable a Pennsylvania Quaker-turned-self-taught-surgeon to see himself as a warrior and leader of men in such a place. And yet Harlan gamely offered to raise an army, invade Afghanistan, depose the usurping prince and restore Shujah to his throne. In return, he told Shujah, he wanted to be made vizier—a high-ranking role that would confer upon Harlan enormous political clout within the country. It was the boldest of plans accompanied by the most audacious of demands, and yet his offer was readily accepted.

Harlan duly raised an army of mercenaries, renegades, mavericks and dreamers, the ranks given a bit of backbone and discipline by the presence of a few

sepoys—

Indian soldiers drilled in the ways of the British Army. He marched them, behind an American flag made specially for the job in Ludhiana, along the British bank of the Sutlej and on into the independent territories existing in the murky hinterland between British India, the Punjab and Afghanistan itself. As well as his few hundred troops, he brought a small fortune in gold and silver coins from Shujah—funds for meeting all traveling expenses and, more importantly, for bribing the many petty chiefs he would encounter along the way.

However unlikely the quest, however dangerous and unpredictable the terrain, Harlan confidently led his motley band deep into the wilds beyond British India. They reached the mighty Indus River that flows from the Himalayas to the Arabian Sea, through a valley that had cradled, each in its turn, the civilizations of the Buddhists,

the Scythians, the Aryans and others besides. Harlan was by now far from any source of Western help or support. The influence of the British was lost behind him and he was now on the fringes of Afghanistan itself. Now it was the rivalries of strangers that would conspire to shape his fate. Ranjit Singh and his Sikhs, and the various Afghan warlords—Dost Mohammed Khan predominant among them from his power base in Kabul—watched each other constantly, vying for opportunities to strike. Now Josiah Harlan of Pennsylvania was among them and about to find the going more treacherously dangerous than before.

While Harlan remained as confident as ever—indeed, thrilled by the seemingly limitless opportunities for self-advancement he saw before him—his army did not. Probably because they knew the dangers more intimately than their commander, the soldiers had allowed themselves to be spooked. Just months into his journey, Harlan awoke one morning to find that the bulk of his men had deserted him in the night. Realizing that force was no longer a realistic option, he dismissed all but a dozen of the remainder and struck out for Kabul—dressed in the garb of a holy man. Harlan was a gifted linguist but had not yet had time to fully acquire either the tongue of the Afghans or the neighboring languages of Persian and Arabic. Rather than trying to talk to those he encountered, and so risking giving himself away as a foreigner—a

feringhee

—he would play dumb and allow the natives to think he was too deep in holy contemplation to bother himself with tittle-tattle.

Whether the locals were fooled—or rather chose to indulge an apparently harmless

feringhee

blessed with useful medical skills—is hard to say. In any case Harlan and his followers reached the city of Peshawar, where he was well treated, before pressing on to Kabul itself, reaching the lair of Dost Mohammed Khan in the spring of 1828.

Harlan was impressed by the city and its master, “a man of slender proportions, tall, and about 37 years of age.” And herein lay the secret of the American’s success: it seems he carried no prejudice, no bigotry and had instead the wisdom of an open mind. He allowed for difference, for points of view that differed from his own. Rather than seeking to judge, to impose his own culture, he absorbed the ways of his hosts. While Britain—and more particularly the British East India Company—sought to control new lands by “making the world England,” Harlan was prepared to be changed by what he experienced.

The time he spent with Dost Mohammed persuaded Harlan that his host was too firmly in place to be routed by any invasion on behalf of Shujah. Abandoning his plans to subvert and overthrow the incumbent in Kabul—having in fact come to admire him—he decided instead to seek his fortune and his empire elsewhere. Dost Mohammed was after all just one ruler among many in the lands beyond Britain’s thrall—and certainly not the most powerful. Ranjit Singh of the Punjab, he had learned, employed a handful of well-paid European mercenaries to lead his forces—and this modern army had made him second only to the mighty British Empire. Ranjit was also a sworn enemy of the King of Kabul and perhaps, reasoned Harlan, his own new-found knowledge about his erstwhile host might endear him to the ruler of the Punjab.

If it looks to our eyes as though the Quaker from Pennsylvania was engaged in a game, moving from square to square on a great chessboard, then that is entirely fitting. Long before Harlan arrived in India, the British Empire had persuaded itself it had an imperial rival in Central Asia. Tsarist Russia had made her own territorial gains. In 1800, the two empires were separated by around 2,000 miles, most of it unmapped and unknown to outsiders. Steadily though, as the early years of the 19th century began to pass, the Tsar’s forces began to make gains at the expense of a third, ancient

empire in the region—that of Persia. In 1813, the first Russo-Persian War was brought to an end by the Treaty of Gulistan. The Persians were on the back foot, and under the terms of the treaty they accepted that the lands known to us today as Azerbaijan, Daghestan and Georgia belonged now to the Tsar.