Read America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents Online

Authors: Charles River Editors

America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents (15 page)

Given Jackson’s temperament, it’s not surprising that he would be an ardent participant in the political bickering. Among Jackson's most controversial moves in Congress was his vote against a letter from Congress thanking George Washington for his service as President. Though it sounds absurd today, Jackson was not alone in opposing the measure. Many members of the Democratic-Republican Party, most of whom were from the South, thought Washington kowtowed too often to Alexander Hamilton, and Jefferson resigned from his post out of frustration after Washington’s first term. Moreover, Washington’s signing of the Jay Treaty, which boosted the country’s trade relations with Britain and pitted it against the French, infuriated Democratic-Republicans who had naturally favored France, the principal ally during the American Revolution. And to top it all off, many of the Democratic-Republicans suspected (correctly) that Washington’s farewell address had Hamilton’s fingerprints all over it, leaving them in no mood to make niceties.

With this, Jackson offered the first insight into his political philosophy. He was a staunch defender of states' rights in the Jeffersonian model and was no fan of the Federalists or George Washington. Jackson proclaimed a narrowly conservative understanding of the federal government and was unwilling to allow the central government to infringe on the rights of the states. A good South-Westerner, Jackson was in lock-step with Thomas Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans, though he and later politicians of his ilk added a uniquely rugged, “western” tinge to the party's ideology.

Jackson's time in the House was short lived. In the spring of 1797, the always restless Jackson eyed a more appealing opportunity: Major General of the Tennessee Militia. At the time, each state maintained a militia, with a Major General at the top, and Jackson had an appealing pedigree as a Congressman and a veteran of the Revolution. Unfortunately for Jackson, the position was an elected one, and the young man lost the election.

However, his loss proved to be only a minor setback. Later that year, Jackson was elected to represent Tennessee in the United States Senate, for a six-year term. Much like his time in the House, Jackson worked hard but was not terribly influential. He never participated in debates in the Senate, and his record in the chamber is almost entirely blank. One thing was clear, however: just as Jackson was no fan of President Washington, he held President Adams with as much contempt.

Judge and Planter

With a fairly bare record and not much influence, Jackson quickly found he was not enjoying his time in the Senate, which he considered to be too stuffy and elitist. The rough-and-tumble life on the frontier appealed to Jackson more than the political halls of Washington, D.C. As a result, he resigned after less than a year in office, once again with an eye on another office. This time, Jackson was eyeing a gavel, not a gun, hoping to be elected to the Tennessee Superior Court. Running unopposed, Jackson was elected to a seat on the Court by the state legislature in 1798, at the age of 31.

Much of Jackson's work on the court, like his work as Solicitor earlier, focused on common disputes and general misbehavior. He served diligently on the court for six years, and was by all accounts a strong judge, but being a justice did not occupy all of Jackson's time. During his free time, Jackson prospered as a planter and land speculator, trading on his nearly 15 years of experience living on the frontier. He owned an estate with numerous slaves, growing mostly cotton, and he also formed business partnerships and opened a general store in Gallatin, Tennessee. Civic obligations were also important to Jackson, who founded the first Masonic Lodge in Nashville in 1801.

Jackson had gained a seat on the court and had been elected to both branches of Congress, but he still wanted the position that had initially eluded him. In 1802, he finally got the position he had longed hope for when he was elected the Major General of the Tennessee Militia. In an arrangement that sounds impossible today, Jackson served as a judge while maintaining and commanding the state's military.

Jackson had proven unwilling to finish the terms of elected office in his first 31 years, so naturally by 1804, Jackson was beginning to tire of being a judge. Thus, he resigned from the court to focus all of his efforts on planting and business. This included purchasing his estate, the Hermitage, in August of 1804.

The Hermitage

Chapter 3: The War of 1812

The War of 1812

Nearly a majority of the presidents of the United States during the 19

th

century were military veterans, with war heroics often serving as a politician’s primary argument in favor of their candidacy. The mold would be set by Andrew Jackson, whose military stardom began with the outbreak of a civil war among Creek Indian tribes living in modern-day Alabama.

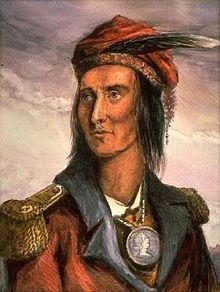

In late 1811, a large and rare earthquake occurred in modern-day Missouri, near the town of New Madrid, and it was so powerful it could be felt throughout the modern Southeast United States. Some Creek Indians living in the region took this seismic event as a call to action, believing they needed to force white settlement out of their region and limit them to an area north of the Ohio River. Shawnee Chief Tecumseh led the “Red Stick” Indians in these ensuing attacks on white settlements in Georgia and Tennessee.

A 19

th

century depiction of Tecumseh

Not all Creek Indians agreed on the need for war, however. Cherokee, Choctaw and Lower Creek Indians joined Andrew Jackson and his Tennessee militia in fighting Tecumseh's invasion North. In 1812 these battles were only made more complicated when war between the United States and Great Britain erupted with the War of 1812. Sensing an opportunity, the British allied with Tecumseh in his fight with Tennessee and Georgia.

When Jackson was in Congress, Democratic-Republicans were still smarting from Jay’s Treaty, which upgraded relations between the young United States and Great Britain. However, Thomas Jefferson’s election in 1800 ushered in a new era for the country, beginning nearly a generation of his party’s rule, and his party’s antagonism toward Great Britain began to manifest itself.

Tensions with Great Britain remained high throughout Jefferson’s presidency, with the primary complaint being that the British continued to impress American sailors. The British would board American vessels and literally force American sailors to work for the Royal Navy for up to five years, subjecting him to the harsh shipboard discipline of the Royal Navy. American sailors were the most appealing targets for impressment by the British because they spoke English. More importantly, American merchants had little influence in Great Britain, unlike British merchants. Thus, the Royal Navy had an easy supply of American sailors to impress, due to the booming trade between Great Britain and the United States that resulted during Washington’s and Adams’s presidencies.

In addition, Great Britain's Parliament passed a series of acts attempting to restrict American merchants from trading with France, with whom Britain was at war since 1793. This became ever more urgent to the British when Napoleon began conquering entire swaths of Europe. Public opinion in the United States was also strongly clamoring for war with Great Britain after Great Britain was found to be arming Native Americans inside the Northwest Territory, a lesson Andrew Jackson and his forces learned all too well. .

Jefferson’s successor, President James Madison, presented a list of grievances against Great Britain to Congress, which voted to declare war on June 18, 1812. At the time, Great Britain was deeply involved in the Napoleonic Wars, but the United States was also not well-prepared for war. Jefferson was distrustful of standing armies and had thus neglected the federal army and navy. At the outbreak of war, American forces were largely comprised of militias like the one Jackson was commanding.

From the beginning, Madison hoped to annex Canada, which the Americans invaded in 1812, much like they had in 1775. Madison’s strategic aim was to force the British to negotiate for peace after losing Canada, and at the least Madison believed that Canada would be a very valuable negotiating chip that could be exchanged with the British for American demands. However, the invasion of Canada went poorly, as American supply lines were stretched and local resistance strong.

As the war dragged on, Great Britain was able to blockade American ports, but Americans were able to win victories around the Great Lakes, and a British invasion of New York failed. The British Royal Navy did raid and burn towns in the mid-Atlantic states, including Washington, D.C. President Madison was forced to flee the White House, which was destroyed.

By 1814, the Native American tribes allied with Great Britain in American territory had largely been defeated, except in the far West. But neither the Americans nor British had achieved any significant territorial gains, and both were suffering from the loss of a major trading partner. Negotiations to end the war began around the end of 1814.

The Battle of Horseshoe Bend

Although the War of 1812 is best remembered for fighting around the Great Lakes, Canada, and the East Coast, battles continued to rage between Americans and the Creeks in the west during the war, largely coordinated by militia forces under the command of Jackson. Fighting culminated in 1814 at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. As part of an effort to “clear” Alabama for white expansion, Jackson and his troops sieged the Red Sticks into a “horseshoe bend” along the Tallapoosa River in Central Alabama. Together with his Cherokee allies, Jackson’s well-trained and well-equipped forces killed over 500 Red Sticks warriors, and then killed others as they tried to flee across the Tallapoosa River. After five hours of fighting, they surrendered, and the Creek War was over. The Red Sticks were forced to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson, which forced them to vacate all of Georgia and Alabama for white settlement.

With the victory at Horseshoe Bend, Andrew Jackson was now a military hero. Because he was “as strong as old hickory,” he acquired the nickname “Old Hickory”, and the battle also heaped military glory on Sam Houston, whose bravery and wound helped earn him acclaim. Houston would earn more fame in Texas over 20 years later, when Jackson was president.

Battle of New Orleans

19

th

century depiction of Jackson at New Orleans

There are countless examples of battles that take place in wars after a peace treaty is signed. The last battle of the Civil War was a skirmish in Texas that Confederate forces won, nearly a month after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. But it’s rare for the most famous battle of a war to take place after the peace treaty is signed.