America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents (20 page)

Read America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents Online

Authors: Charles River Editors

Lincoln had to travel a lot as a prairie lawyer, and in many cases he slept in the same bed with men that accompanied him, the best known being Joshua Speed. Between sleeping in the same bed and writing heartfelt letters, both of which were common 19

th

century customs among men, some have speculated that Lincoln and Speed had a homosexual relationship, although no evidence bears that out.

Lincoln loved the law, but there was one thing he loved more: politics. In 1843, Lincoln sought the Whig nomination for a seat in the U.S. Congress representing Illinois' 7

th

Congressional District. The Illinois 7

th

was one of few Whig districts in the state; winning the Whig nomination meant an almost certain victory in the general election. All Lincoln had to do was win the nomination.

But he didn't. At first, Lincoln took the defeat quite hard. Unlike his first loss for the State Legislature seat, Lincoln's chances of winning weren't horrible. Furthermore, Lincoln was partly defeated because he was attacked as a candidate of wealth and aristocracy.

Lincoln of all people

was labeled a member of the elite, a charge he misunderstood and deeply despised. Attacks on his character – that he was a drunk, a deist and an aristocrat – all sunk his chances of victory, despite the fact that they were all completely inaccurate.

Despite initial disappointment, there was some hope to be gleamed out of defeat: at the nominating convention, Lincoln managed an agreement known as the “Pekin Agreement,” which meant that the Whig nominee for the 7

th

Seat would rotate every two years. Its purpose was to secure “party unity,” by ensuring that different people led the party and brought different constituencies to the coalition. With this, Lincoln was assured of being nominated in the election of 1846, and he won a seat in the US Congress representing the Illinois 7

th

District as a Whig. At the same time, however, this ensured he could only serve one term.

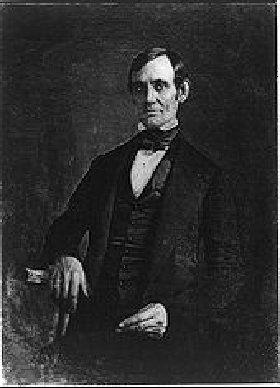

Lincoln in his 30s

Congressman Lincoln

Knowing he had 2 years with which to work, Lincoln had grand ideas about his time in Congress. Upon arriving in Washington, however, reality struck. Lincoln was one of many freshman members of Congress, received no important appointments, and his influence would be minimal.

Regardless, Lincoln used his time in Congress to toe the Whig party line by echoing the Whig leadership in speeches and votes. Just as in the State Legislature, Lincoln was an adamant Clay devotee. He supported Clay in lock-step on tariffs and internal improvements.

The most prominent part of Lincoln's Congressional career was his staunch opposition to the Mexican-American War, the only aspect of Lincoln’s political career that most Americans (including his political opponents) were aware of as late as 1860. To Lincoln, “President Polk's War” was full of deception. Contrary to Polk's accusation that the war was defensive – according to the President, Mexicans had fired on American troops in the Rio Grande – Congressman Lincoln thought the war was unnecessary aggression. To Lincoln, the Rio Grande area was disputed territory, and more likely Mexican, seeing as it was occupied by Spanish-speaking Mexicans. Going to war over a disputed territory that was only dubiously claimed by Texas simply did not make sense. But Lincoln’s attempt to force the President to show the precise spot where American soldiers were attacked, later known as the Spot Resolutions, went nowhere.

Lincoln's anti-war activities were not popular in his home district in Illinois, and newspapers and Democrats across the state accused Lincoln of treason. The last American war that attracted significant opposition – the War of 1812 – had led to talk of New England secession. Opposition to another war was thus tinged with treasonous potential.

Despite Lincoln and the Whigs' opposition, the Mexican-American War continued as planned, culminating with the acquisition of substantial southwestern territory. Moreover, it was this experience that prepared many young West Point cadets and middle aged military officers for the Civil War about a decade later. In the 1850s, however, the conquest of the Southwest led to further agonizing over slavery. Because of this, Lincoln was now poised to give a major opinion on the issues of slavery: what would be the status of slavery in this newly-obtained territory? Lincoln supported the Wilmot Proviso, which would have banned slavery in all territory acquired from Mexico. That stance is telling about Lincoln's later Presidency.

The truth of Lincoln's slavery position while in Congress, however, is that it was mixed. Aside from the Wilmot Proviso, Lincoln tended to waver on the question of slavery. During his first session in Congress, Lincoln supported reading abolitionist petitions to Congress. In his second session, he opposed this. He opposed the existence of slavery in Washington, D.C., but he supported fugitive slave laws. Apart from Wilmot, however, Lincoln's statements on slavery were limited. Even until the last days of his Presidency, it is probably fair to characterize Lincoln's views on race and slavery as constantly evolving.

Abiding by the Whig rules of Congressional rotation, Lincoln let another Whig run for the 7

th

District seat in 1848. Unlike in previous elections – when the Whig nominee was virtually guaranteed victory in November – the party's nominee lost in 1848. Lincoln was taken aback. Whig defeat in a staunchly Whig district seemed a repudiation of Lincoln himself, especially his anti-war views. But the verdict wasn't that clear. The Democrats had nominated a popular war hero, and the Whig nominee was something of a grouch. Furthermore, the Whig nominee for President – Zachary Taylor – won Lincoln's district, and the national election altogether.

Chapter 3: Lincoln in the 1850s

Tragedy

After leaving Congress, Lincoln returned to Springfield to practice law. For the most part, Lincoln remained a “prairie lawyer,” though a prominent and successful one. It was during this time that he first crossed paths with a young engineering prodigy who was working on railroad lines after graduating second in his class at West Point. But Lincoln and George B. McClellan would not take real notice of each other until 1861.

In his personal life, the Lincoln family was struck by tragedy in early 1850. The family's second son, Eddie, died on February 1

st

. The cause of death was likely tuberculosis. Mary collapsed with sadness. For weeks after, she remained in her bedroom weeping, refusing to eat. Indeed, Mary would never be the same again. After Eddie’s death, her temper was shorter, her anxiety higher and her insecurity more pervasive.

Regardless, the family had a third son, William Wallace, in December of 1850.

The Compromise of 1850

Lincoln's personal distress mimicked the pains the nation was experiencing in 1850. The sectional crisis was brewing like never before. California and the newly-acquired Mexican territory were now ready to be organized under statehood. How to do this without offsetting the slave-free state balance was tearing the nation apart.

Out of this crisis emerged the Compromise of 1850: a landmark piece of legislation authored by Lincoln's beloved Henry Clay. The Compromise admitted California to the Union as a free state and allowed Utah and New Mexico to decide the issue of slavery on the basis of popular sovereignty, an idea ironically championed by Lincoln’s best known political opponent, Stephen Douglas. It also abolished the slave trade – though not the existence of slavery itself – in Washington, DC, and issued a fugitive slave law that required runaway slaves be returned to their masters.

Lincoln, always a Clay man, commended the Compromise. He thought it to be a moderate, pragmatic proposal that did not decidedly extend the existence of slavery, and put slow and steady limits on the peculiar institution. Furthermore, it put the maintenance of the Union as a top priority.

When Henry Clay died in 1852, Lincoln issues a rousing public eulogy. He praised Clay's nationalism, his moderate anti-slavery views and his love of the Union. Lincoln remained popular in Illinois Whig circles, and many looked to him to eulogize Clay.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act

Through 1853 and 1854, however, Henry Clay's Compromise of 1850 came under assault. The Compromise did not settle

all

territory needed to be admitted for statehood. In an attempt to organize the center of North America – Kansas and Nebraska – without offsetting the slave-free balance, Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois proposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

Kansas-Nebraska proved to be the straw that broke the camel's back. This was true for both the nation and Abraham Lincoln himself. First, the Kansas-Nebraska Act eliminated the Missouri Compromise line of 1820, which the Compromise of 1850 had maintained. This line stipulated that states north of the line would be free and states south of it

could

have slavery. This was essential to maintaining the balance of slave and free states in the Union. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, however, ignored the line completely and proposed that all new territories be organized by popular sovereignty. Settlers could vote whether they wanted their state to be slave or free.

When popular sovereignty became the standard in Kansas and Nebraska, the primary result was that thousands of zealous pro-slavery and anti-slavery advocates both moved to Kansas to influence the vote, creating a dangerous (and ultimately deadly) mix. Numerous attacks took place between the two sides, and many pro-slavery Missourians organized attacks on Kansas towns just across the border.

The best known abolitionist in Bleeding Kansas was a middle aged man named John Brown. A radical abolitionist, Brown organized a small band of like-minded followers and fought with the armed groups of pro-slavery men in Kansas for several months, including a notorious incident known as the Pottawatomie Massacre, in which Brown’s supporters murdered five men. Over 56 people died until John Brown left the territory, which ultimately entered the Union as a free state in 1859.

The Republican Party

Lincoln, Whigs and Free Soilers were aghast over the Kansas-Nebraska Act. How could Congress now – theoretically – allow slavery to extend into

any

unsettle territory? This strictly violated some of Lincoln's (and, previously, Clay's) dearest held principle that the further extension of slavery should not extend further. Whigs and Free Soilers in the North quickly coalesced against the “Slave Power.” They felt Southern influence in Washington had gone too far and held the government in a strangle-hold.

This coalescence first became known as the “anti-Nebraska” group, but quickly vowed to form a new political party dedicated to keeping the Western territories free from slavery. They called themselves the Republicans.

Although destined to be forever associated with the Republican Party, Lincoln remained a Whig for some time. He agreed with the Republicans on the issue of Kansas-Nebraska, but wasn't yet convinced that the Party of Clay was on its last legs. Instead, Lincoln focused his efforts on Stephen Douglas, the “Little Giant.”

The day after a major speech given by Douglas in which he defended his Kansas-Nebraska Act, Lincoln gave a speech known as the “Peoria Speech.” On October 16

th

, 1854, for the first time, the North would take note of Abraham Lincoln.

In his speech, Lincoln laid out his opinion on slavery, a position he would keep only until the very last months of his Presidency. It can be summed up best by Lincoln himself: “I wish to make and to keep the distinction between the existing institution, and the extension of it, so broad, and so clear, that no honest man can misunderstand me.”

[3]

Lincoln conceded the South's constitutional right to the maintenance of slavery in their states, but he firmly pushed back on the idea that it needed to be extended beyond where it already existed. Lincoln said he thought slavery would die out on its own with time, and that this was the position of the Founders. Federal intervention was not needed to abolish slavery. Popular sovereignty was wrong because it allowed anyone to bring slaves into new territory, and thereby extend the institution into new states. Its extension -

anywhere

– was what Lincoln wanted to disallow.

With this speech, Lincoln was now considered a leader of the anti-Nebraska men in Illinois. Anti-Nebraskaism swept Illinois in 1854, earning Lincoln a seat in the State Legislature again. The seat, however, was in the way of Lincoln's greater ambitions: a seat in the U.S. Senate. He resigned to run for Senate as a Whig, which he campaigned for throughout 1855.