America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents (22 page)

Read America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents Online

Authors: Charles River Editors

The Crittenden Compromise failed on December 18. Two days later, South Carolina seceded from the Union. President Buchanan sat on his hands, believing the Southern states had no right to secede, but that the Federal government had no effective power to prevent secession. In January, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Kansas followed South Carolina's lead. The Confederate States of America (CSA) was formed on February 4

th

, in Montgomery, Alabama, with former Secretary of War Jefferson Davis as its President. On February 23

rd

, Texas joined the CSA.

Abraham Lincoln hadn't yet assumed office, and yet he had an unprecedented crisis on his hands. Today, Lincoln is remembered as his country’s greatest President, but he began his presidency as its least popular ever.

Chapter 5: Early Presidency and the Start of the Civil War, 1861-1863

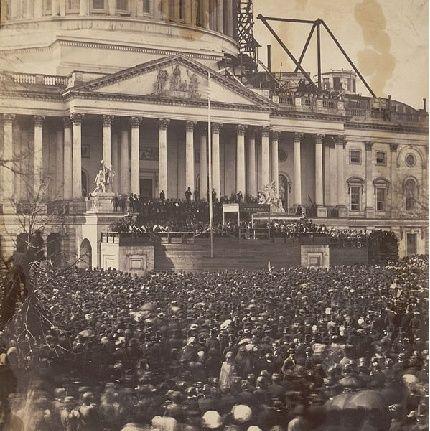

The Capitol Dome was still being worked on before Lincoln’s inauguration

Inauguration

On March 4, 1861, Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney inaugurated Abraham Lincoln as the 16

th

President of the United States, but there was no love lost between the two men. Taney is now notorious for his decision in the

Dred Scott

case, and he long considered Lincoln a usurper of power.

In his Inauguration Speech, Lincoln struck a moderate tone. Unlike most Inauguration Addresses, which are typically followed by balls and a “honeymoon” period, Lincoln's came amid a major political crisis. To reassure the South, he reiterated his belief in the legal status of slavery in the South, but that its expansion into the Western territories was to be restricted. He outlined the illegality of secession and refused to acknowledge the South's secession, and promised to continue to deliver US mail in the seceded states. Most importantly, he pledged to not use force unless his obligation to protect Federal property was restricted:

“In doing this there needs to be no bloodshed or violence, and there shall be none unless it be forced upon the national authority. The power confided to me will be used to hold, occupy, and posess the property and places belonging to the Government and to collect the duties and imposts; but beyond what may be necessary for these objects, there will be no invasion, no using of force against or among the people anywhere.”

[4]

Fort Sumter

In his First Inaugural Address, Lincoln promised that it would not be the North that started a potential war, but he was also aware of the possibility of the South initiating conflict. After he was sworn in, Lincoln sent word to the Governor of South Carolina that he was sending ships to resupply Fort Sumter, to which the governor replied demanding that federal forces evacuate it. Southern forces again fired on the ship sent to resupply the boat, and on April 12, 1861, Confederate artillery began bombarding Fort Sumter itself. After nearly 36 hours of bombardment, Major Robert Anderson called for a truce with Southern forces led by P.G.T. Beauregard, and the fort was officially surrendered on April 14. No casualties were caused on either side by the dueling bombardments across the harbor, but, ironically, two Union soldiers were killed by an accidental explosion during the surrender ceremonies.

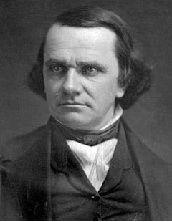

After the attack on Fort Sumter, support for both the northern and southern cause rose. President Lincoln requested that each loyal state raise regiments for the defense of the Union, with the intent of raising an enormous army that would subdue the rebellion. In hearing of this action, Stephen Douglas – many times Lincoln's chief rival – declared his support for President Lincoln. They met in the White House to go over plans for war, and afterwards Douglas devoted the remaining years of his life to supporting President Lincoln and the Union cause. They wouldn’t be many, though, as the Little Giant died in June 1861.

Stephen Douglas

However, four states which had been avoiding seceding or declaring support for the Union seceded after Lincoln's call for volunteers. The Confederate States of America now consisted of South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina and Tennessee. The border states of Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware remained in the Union, but the large number of southern sympathizers in these states buoyed the Confederates’ hopes that those too would soon join the South.

The loss of these border states, especially Virginia, all deeply depressed Lincoln. Just weeks before, prominent Virginians had reassured Lincoln that the state's historic place in American history made its citizens eager to save the Union. But as soon as Lincoln made any assertive moves to save the Union, Virginia seceded. This greatly concerned Lincoln, who worried Virginia’s secession made it more likely other border states and/or Maryland would secede as well.

The First Battle of Bull Run

Despite the loss of Fort Sumter, the North expected a relatively quick victory. Their expectations weren’t unrealistic, due to the Union’s overwhelming economic advantages over the South. At the start of the war, the Union had a population of over 22 million. The South had a population of 9 million, nearly 4 million of whom were slaves. Union states contained 90% of the manufacturing capacity of the country and 97% of the weapon manufacturing capacity. Union states also possessed over 70% of the total railroads in the pre-war United States at the start of the war, and the Union also controlled 80% of the shipbuilding capacity of the pre-war United States.

Although the North blockaded the South throughout the Civil War and eventually controlled the entire Mississippi River by 1863, the war could not be won without land battles, which doomed hundreds of thousands of soldiers on each side. This is because the Civil War generals began the war employing tactics from the Napoleonic Era, which saw Napoleon dominate the European continent and win crushing victories against large armies. However, the weapons available in 1861 were far more accurate than they had been 50 years earlier. In particular, new rifled barrels created common infantry weapons with deadly accuracy of up to 100 yards, at a time when generals were still leading massed infantry charges with fixed bayonets and attempting to march their men close enough to engage in hand-to-hand combat.

After Fort Sumter, the Lincoln Administration pushed for a quick invasion of Virginia, with the intent of defeating Confederate forces and marching toward the Confederate capitol of Richmond. Lincoln pressed Irvin McDowell to push forward. Despite the fact that McDowell knew his troops were inexperienced and unready, pressure from the Washington politicians forced him to launch a premature offensive against Confederate forces in Northern Virginia. His strategy during the First Battle of Bull Run was grand, but it proved far too difficult for his inexperienced troops to carry out effectively.

McDowell’s army met Beauregard’s Confederate army near a railroad junction at Manassas on July 21, 1861. Located just 25 miles away from Washington D.C., many civilians from Washington came to watch what they expected to be a rout of Confederate forces. Instead, Confederate reinforcements under General Joseph E. Johnston arrived by train in the middle of the day, a first in the history of American warfare, and troops led by Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson helped turn the tide. As the battle’s momentum switched, the inexperienced Union troops were routed and retreated in disorder back toward Washington in an unorganized mass. With over 350 killed on each side, both the Confederacy and the Union were quickly served notice that the war would be much more costly than either side had believed.

Despite Union successes in the Western theater during 1861, the focus of the Administration remained concentrated on Richmond. Lincoln's first major move was to dismiss General McDowell and replace him with General George B. McClellan in the fall of 1861. McClellan, known as “The Young Napoleon”, had already conducted a successful campaign in western Virginia, at times besting a former U.S. military officer named Robert E. Lee.

McClellan had been a foreign observer at the siege of Sevastopol during the Crimean War nearly a decade earlier. This experience made him fit for commanding an army, but it also colored his military ideology in a way that was at odds with a Lincoln Administration that was eager for aggressive action and movement toward Richmond.

The War was certainly going badly. And in early 1862, Lincoln's personal life took a turn for the worse when his son, Willie, died of typhoid in February. Lincoln was certainly sad, but Mary was distraught. Despite being a wartime President, Lincoln offered no correspondence with members of the government for four days after his son's death. Mary, on the other hand, spoke to no one for months. She was truly heart broken.

Union Defeats and Rising Anti-War Sentiment in the North

Under McClellan, and at Lincoln's urging, the Army of the Potomac conducted an ambitious amphibious invasion of Virginia in the spring of 1862. McClellan hoped to circumvent Confederate defenses to the north of Richmond by attacking Richmond from the southeast, landing his giant army on the Virginian peninsula. McClellan originally surprised the Confederates with his movement, but the narrow peninsula made it easier for Confederate forces to defend. One heavily outnumbered force led by John Magruder held out under siege at Yorktown for nearly an entire month, slowing the Army of the Potomac down.

Nevertheless, McClellan’s army could see the church spires of Richmond by the end of May 1862. McClellan did not seize the initiative and instead began a slow, methodical approach to Richmond that allowed the Confederates to build defenses and gather men for a defense. Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston, having no more room to withdraw, struck at the Army of the Potomac at the Battle of Seven Pines on May 31, 1862. Although the Confederates were not victorious, the attack rattled the Army of the Potomac. Moreover, Johnston was injured, forcing President Jefferson Davis to replace him with Robert E. Lee.

Upon taking command, Lee immediately took the offensive, attacking the Army of the Potomac repeatedly in a flurry of battles known as the Seven Days Battles. Fearing he was heavily outnumbered, McClellan began a strategic retreat, and despite badly defeating the Confederates at the Battle of Malvern Hill, the last battle of the Peninsula Campaign, it was clear that the Army of the Potomac was quitting the campaign. The failure of McClellan's campaign devastated the morale of the North, as McClellan had failed to advance despite originally having almost double the manpower.

McClellan was quitting the field, but Lee was just getting started. With experienced and trustworthy subordinates like Stonewall Jackson and James Longstreet, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia swung back toward Northern Virginia and beat back another Union army under John Pope that was advancing toward Richmond from the north. This battle was fought on nearly the same ground as First Bull Run, but with many more soldiers and casualties than the first battle. Like First Bull Run, the Second Battle of Bull Run was a decisive Confederate victory, and Union forces again scurried back to Washington D.C. Moreover, the victory opened up a path for Lee’s army to invade Union territory and try to break the North’s morale and/or win foreign recognition, and the promise of intervention with it.

In these losses, the Union suffered more than 20,000 casualties, and Northern Democrats, who had been split into pro-war and anti-war factions from the beginning, increasingly began to question the war. As of September 1862, no progress had been made on Richmond; in fact, a Confederate army was now in Maryland. And with the election of 1862 was approaching, Lincoln feared the Republicans might suffer losses in the congressional midterms that would harm the war effort.