Ancient Aliens on the Moon (28 page)

Read Ancient Aliens on the Moon Online

Authors: Mike Bara

143:22:08, Cernan: “Well, I have some good pictures of Nansen, anyway, and… (long pause)… You know, I look out there, I’m not sure I really believe it all.”

A bit later, completely out of context, Schmitt seems to address their “off-camera” time to mission control:

143:27:11, Schmitt: “We haven’t had a chance to look around anymore than you’ve heard.”

143:27:14, Parker: “Okay.”

Is this an indication that they

didn’t

descend into Nansen during their off-camera time? And what was so unbelievable about Nansen that Cernan had to mention it? Certainly, there is nothing in the released images of the station that implies anything unusual.

Next, Cernan and Schmitt drove to station 2A, just a few hundred meters back down the slope they had ridden up to get to the lip of Nansen. From this perspective, they could have had a perfect vantage point looking directly into the hole leading into the South Massif.

Amazingly, there are officially no pictures taken of Nansen from this perspective, looking directly into the opening under the ledge and back up at the previous geology station. However, at station 2A, Cernan turned the rover in a circle, so Schmitt could take a panoramic view of the area and the valley below them. As he did so, there was this exchange:

143:50:20, Cernan: “Wait a minute. Wait a minute. Okay. Let’s take one from right here. I want the whole thing. (Pause.) You ready to start?”

143:50:26, Schmitt: “Yeah, I got it.”

143:50:27, Cernan: “Start taking. Take the whole thing.”

143:50:54, Cernan: “Isn’t that something? Man, you talk about a mysterious looking place.”

143:51:03, Schmitt: “They can cut some frames—some parts of those pictures out—and make a nice photograph.”

According to the transcripts, the pan “turned out to be relatively uninteresting because of the sun glare.” Published images do not seem to be a full 360° pan, because if they were, the entrance down into Nansen would be visible. In fact, it’s nowhere on the published sequences of this area. And how does Cernan’s statement “Man, you talk about a mysterious looking place” jibe with the “relatively uninteresting” description given in the transcripts? This whole area seems to be fascinatingly anomalous, so much so that Cernan stopped to make sure Schmitt got a complete photographic record of it. A record, incidentally, which now does not correspond to the descriptions of the astronauts at that time. And what about Schmitt’s nervous talk about cutting “some parts of those pictures out?” What does he see that NASA doesn’t want the folks back home to see?

Maybe this. At some point after they arrived at geology station 2 above Nansen, Schmitt took a series of photographs that show the floor of the Lunar Rover vehicle, frames AS17-135-20676 to 20679. But the last photo in this magazine, AS17-135-20680, is listed as “LRV Floor? Sunstruck” in the NASA Apollo 17 image library.

3

It is a very noisy and over exposed image. But when the noise is removed, it takes the shape of a very pyramidal looking object, which may or may not be part of the Rover itself.

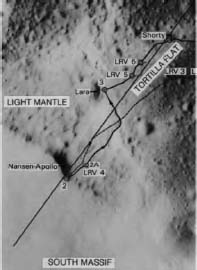

EVA-2 traverse map showing the locations of geology stations 2 and 2A at the base of the South Massif. Note that station 2A would allow a direct view into the Nansen opening.

Is it possible that Schmitt was supposed to take the pictures looking directly into Nansen from the north near geology station 2a, and forgot to change film magazines? If he had been tasked with taking the photos of Nansen from the non-public perspective, the one that we were never supposed to see, maybe there was a special “black” film magazine he was supposed to use? Maybe the “Chapel Bell” film magazine?

If this is true and Schmitt simply forgot about the one errant frame he took of Nansen’s interior, then it is possible that this is one of the long sought images that were part of the classified part of the mission to Taurus-Littrow. Certainly, the provenance of this photo implies at least some desire on NASA’s part to discourage anyone from ordering it or looking at it. While it is listed in the Apollo 17 image library, it is misidentified as being part of magazine 135 (G). In fact, it might be part of magazine 136 (H). So the correct frame number could be AS17-136-20680. However, you will not find it on any NASA web site with this designation, and the Apollo17 photo index from the 1970’s lists that frame number as “blank,” which it obviously is not.

2

And, on the NASA Lunar and Planetary Institute web site, the frame doesn’t exist at all. Frames AS17-135-20680 (magazine G) and AS17-136-20681 (magazine H) are simply missing.

AS17-135-20680

As you read back through the transcripts, it’s clear from the comments of the astronauts that something is amiss. First, Cernan is concerned that they can see directly into Nansen, so much so that he parks the rover up over the lip of Nansen so the TV cameras can’t see directly into the opening. Schmitt—the trained scientist—is so astonished as he looks into Nansen for the first time that he exclaims, “Look at Nansen!” Cernan goes on to describe the whole area as a “mysterious place,” and “unbelievable,” and Schmitt cryptically informs Mission Control that the astronauts “haven’t had a chance to look around anymore than you’ve heard,” despite their thirty-plus minutes off-camera.

Later, as they take pictures that should show what lies beneath the shadowed “overhang” of Nansen (which is clearly visible from orbit), they joke about cutting out certain parts of the pictures. And in all this time, not once did they take a picture showing Nansen from a vantage point that would reveal the interior of the “crater.” They evidently just missed the opportunity, and nobody at Mission Control decided to ask for such a picture.

The reality, however, is that between their off-camera time and the traverse to Station 3, the astronauts would have had plenty of time to descend from the rise and examine and photograph the interior of Nansen. That these photos could have been simply lifted from the photographic catalogs is easy to conceive, especially given the shenanigans around AS17-136-20681. It’s possible that Schmitt and Cernan found that getting into the South Massif through Nansen was impractical. There were descriptions of a great deal of debris in the crater. Or perhaps they tried and failed, leading to Schmitt’s admission that they didn’t get to look around as much as they wanted to.

Whatever the case, they were on a tight timetable to get on with the other stations. What they could not have known, however, was that they were also on a collision course with an even more unbelievable and mysterious encounter, with “Data’s Head.”

“Mr. Data, your head is not an artifact.”

– Commander Riker, from the

Star Trek: The Next Generation

episode “Time’s Arrow.”

I still distinctly remember the first time Richard C. Hoagland showed me the picture of “Data’s Head.” I don’t think I will ever forget it. I was sitting on the couch of his office in Albuquerque, New Mexico, looking at some images he was showing on a big blank wall with a projector. This was the last of several “Dark Mission” summits we’d had to settle on the contents of that book in 2006, and I was anxious to get back to my home in Los Angeles, not the least of which was because L.A. has two things Albuquerque does not; moisture and oxygen. I was tired, cranky, and ready to get to bed. “Don’t be so restless,” he said mysteriously. “I’ve got one more thing to show you.”

Yeah.

There, slowly but surely, building the tension in the way that only he can, he took me through some of the data that you have just seen and read. Then we began to focus in on the last major stop of EVA-2, Shorty crater.

Along the way to Shorty Crater, a black, halo-rimmed volcanic crater on the outskirts of the light mantle material from the South Massif avalanche, Schmitt and Cernan stopped to take some samples along the rim of another small crater, which came to be known as “Ballet Crater.” It was thus dubbed because Schmitt had taken an exceptionally entertaining spill there while trying to retrieve some sample bags. The stop, which was supposed to last twenty minutes, was made to take a double core sample, get a gravimeter reading, and take some photographic pans of the general area (again, notice that Nansen seems to be the only stop on EVA-2 that what not photographed in extensive detail, at least officially). It took nearly thirty-seven minutes for the astronauts to complete their tasks at Ballet Crater, and from there it was straight on to Shorty, which was a primary stop for the EVA along with Nansen. Upon arrival at Shorty, the astronauts took care of some housekeeping chores, and then got their first look at the crater itself. In looking at the transcript of EVA-2, what they saw apparently astounded them:

145:22:22, Schmitt: “Shorty is a crater, the size of which you know. It’s obviously darker rimmed, although the fragment population for most of the blanket does not seem too different than the light mantle. But inside… Whoo, whoo, whoo!”

Schmitt’s description seemed to imply that while Shorty was relatively unspectacular on the outside, the area inside the crater was, at the least, very interesting. Unfortunately, when the camera started up, it was pointed at the distant South Massif. It stayed positioned there as Schmitt moved away to take a panorama of the crater. Later, Cernan took a panorama of the entirety of Shorty crater (NASA frames AS17-137-20991 to 21027).

My first mind-blowing moment was when Richard showed me his color enhancement of Cernan’s panorama. It was filled with stunning colors; blues, purples, pinks and greens, yet the white of the space-suited astronauts were pure white. It was then that he told me of his theory of light bending prismatic effects of the glass-like ruins overhead. I was even more stunned when I saw the famous orange soil that Cernan had spotted.

The orange soil turned out to be highly oxidized titanium, but it was nothing compared to what he showed me next inside the crater itself. I could instantly see what had made Schmitt so excited when he first looked down into Shorty. Rather than the normal looking rocks, boulders and debris I had been expecting, my engineers eye immediately focused on objects inside the rim of the 100-yard-wide crater that were quite obviously mechanical in origin.

Black and white version of NASA frame AS17-137-20990, showing the heavily oxidized orange soil near Shorty crater.

Mechanical objects have certain features and tell-tale design aspects that clearly differentiate them from rocks and other random forms of nature. These include flanges, opposable handles, vents, heat sinks and all manner of connecting hoses, tubes and fixtures. These types of objects, these mere “rocks,” as NASA would claim, were scattered all over the inside of Shorty crater. Most of them had clear (to my eye at least) mechanical features, fixtures and functions. We have a guiding principal in engineering design, which we call the “3 Fs,” Form, Fit, and Function. If whatever you are adding to a part or an assembly doesn’t enhance one of those characteristics, it doesn’t serve a real purpose other than to make you feel clever. The pieces of machinery I saw in Shorty crater all had discernible form, fit and function, and that is what made it clear to me I wasn’t just looking at rocks.