B0041VYHGW EBOK (121 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

To summarize: sound may be diegetic (in the story world) or nondiegetic (outside the story world). If it is diegetic, it may be onscreen or offscreen, and internal (subjective) or external (objective).

In most sequences, the sources of the sounds are clearly diegetic or nondiegetic. But some films blur the distinction between diegetic and nondiegetic sound, as we saw in the cavalry rescue scene from

Stagecoach.

Since we’re used to identifying a sound’s source easily, a film may try to cheat our expectations.

In Mel Brooks’s

Blazing Saddles,

we hear what we think is nondiegetic musical accompaniment for a cowboy’s ride across the prairie—until he rides past Count Basie and his orchestra

(

7.45

,

7.46

).

This joke depends on a reversal of our expectations about the convention of nondiegetic music. A more elaborate example is the 1986 musical version of

Little Shop of Horrors.

There a trio of female singers strolls through many scenes, providing musical commentary on the action without any of the characters noticing them. (To complicate matters, the three singers also appear in minor diegetic roles, and then they do interact with the main characters.)

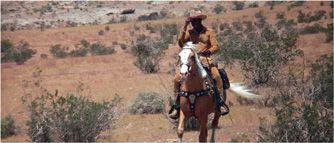

7.45 The hero of

Blazing Saddles

rides jauntily through the desert accompanied by apparently nondiegetic music …

7.46 … until he passes Count Basie’s orchestra, playing within the world of the narrative.

More complicated is a moment in

The Magnificent Ambersons

when Orson Welles creates an unusual interplay between the diegetic and nondiegetic sounds. A prologue to the film outlines the background of the Amberson family and the birth of the son, George. We see a group of townswomen gossiping about the marriage of Isabel Amberson, and one predicts that she will have “the worst spoiled lot of children this town will ever see”

(

7.47

).

This scene presents diegetic dialogue. After this conversation ends, the nondiegetic narrator resumes his description of the family history. Over a shot of the empty street, he says, “The prophetess proved to be mistaken in a single detail merely; Wilbur and Isabel did not have

children.

They had only one.” But at this point, still over the shot of the street, we hear the gossiper’s voice again: “Only one! But I’d like to know if he isn’t spoiled enough for a whole carload”

(

7.48

).

After her line, the narrator goes on, “Again, she found none to challenge her. George Amberson Minifer, the Major’s one grandchild, was a princely terror.” During this description, a pony cart comes up the street, and we see George for the first time

(

7.49

).

In this exchange, the woman seems to reply to the narrator, even though we must assume that she can’t hear what he says. (After all, she’s a character in the story and he isn’t.) Here Welles playfully departs from conventional usage to emphasize the arrival of the story’s main character and the hostility of the townspeople to him.

7.47 In this scene from

The Magnificent Ambersons,

the woman with the teacup makes a remark about Isabel Amberson’s future children …

7.48 … that the nondiegetic narrator’s voice corrects in the next shot.

7.49 As the woman seems to reply to the narrator, Isabel’s son moves into view.

This passage from

The Magnificent Ambersons

juxtaposes diegetic and nondiegetic sounds in a disconcerting way. In other films, a single sound may be ambiguous because it could fall into either category. In the opening of

Apocalypse Now,

the throbbings of the ceiling fan and the helicopter blades are clearly diegetic, but Francis Ford Coppola accompanies these with The Doors’ song “The End.” This might be taken either as a subjective part of the character’s Vietnam fantasy or as nondiegetic—an external commentary on the action in the manner of normal movie music.

Similarly, at a major point in Paul Thomas Anderson’s

Magnolia,

several characters are shown in different locations, each singing softly along to the Aimee Mann song “Wise Up.” When the sequence begins in Claudia’s apartment, the song might be taken as diegetic and offscreen, since she has been listening to Aimee Mann music in an earlier scene. But then Anderson cuts to other characters elsewhere singing along, even though they cannot be hearing the music in Claudia’s apartment. It would seem that the sound is now nondiegetic, with the characters accompanying it as they might do in a musical. The sequence underlines the parallels among several suffering characters and conveys an eerie sense of disparate people for once on the same emotional wavelength. The sound also works with the crosscutting to pull the characters together before the climax, when their lives will converge more directly.

A more disturbing uncertainty about whether a sound is diegetic often crops up in the films of Jean-Luc Godard. He narrates some of his films in nondiegetic voice-over, but in other films, such as

Two or Three Things I Know About Her,

he seems also to be in the story space, whispering questions or comments whose sound perspective makes them seem close to the camera. Godard does not claim to be a character in the action, yet the characters on the screen sometimes behave as though they hear him. This uncertainty as to diegetic or nondiegetic sound sources enables Godard to stress the conventionality of traditional sound usage.

One characteristic of diegetic sound is the possibility of suggesting the

sound perspective

. This is a sense of spatial distance and location analogous to the cues for visual depth and volume that we get with visual perspective. “I like to think,” remarks sound designer Walter Murch, “that I not only record a sound but the space between me and the sound: The subject that generates the sound is merely what causes the surrounding space to resonate.”

Sound perspective can be suggested by volume. A loud sound tends to seem near; a soft one, more distant. The horses’ hooves in the

Seven Samurai

battle and the bugle call from

Stagecoach

exemplify how rising volume suggests closer distance. Sound perspective is also created by timbre. The combination of directly registered sounds and sounds reflected from the environment creates a timbre specific to a given distance. Timbre effects are most noticeable with echoes. In

The Magnificent Ambersons,

the conversations that take place on the baroque staircase have a distinct echo, giving the impression of huge, empty spaces around the characters.

As the camera follows a character, changes in sound perspective may suggest the character’s movement through space, a sort of sonic point of view. But many uses of sound perspective don’t try to be realistic. In a long shot, a character’s voice will usually be clearer than if we were the same distance from her or him in reality, and when we cut to a close-up, that character’s voice will not be significantly louder or crisper. In a conversation with sound overlaps, like the one in

The Hunt for Red October

(

p. 277

), the voices don’t change perspective when the camera shifts to show the listener.

Sound perspective is particularly marked in telephone conversations. Typically, the film’s narration cuts back and forth between the people talking, and the sound perspective varies accordingly. When the person on camera is speaking, the lines are clear and enhanced by natural ambient sounds. The voice heard over the receiver is usually more coarsely rendered and more reverberant, carrying lower pitches and providing little ambient sound. Sound editors call this disparity the

telephone split.

It represents the fact that the listener is hearing a voice on the line, but it seldom matches what a phone call sounds like in reality.

Like all conventions, the telephone split can be adjusted for expressive possibilities. In

Phone Booth,

a publicist is trapped in a booth, pinned down by an unseen sniper who keeps him talking on the phone. Here the telephone split takes an unusual form. The PR man is heard normally, with ambient sound, but we don’t hear the sniper as a crackling telephone voice. Instead, we hear soft, closely miked speech in a dry sound envelope. It does not change when the camera moves toward or away from the booth. The voice has a slight electronic twang, so it doesn’t sound as neutral as a narrator’s voice-over, but it remains closer to our perspective than to the protagonist’s. Whispering, laughing, making rude remarks about what’s happening around the booth, the sniper’s voice hovers in a realm somewhere between us and the street. It enhances the sense that the protagonist is being watched by a distant, somewhat ghostly threat.