B0041VYHGW EBOK (120 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

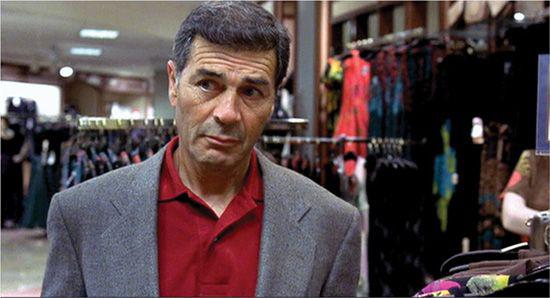

7.32 Third run-through: Pretending to be killing time in the shop, Max turns his attention to Jackie …

7.33 … just as the clerk exclaims, “Wow, you look really cool!” The repeated line anchors us in action we know. The framing from Max’s optical point of view varies what we saw in

7.24

and

7.28

.

While Max is watching the action at the counter, we hear Louis and Melanie quarreling, and this motivates another switch in Max’s attention, in time for him to observe her exclaiming, “Hey, would you let go!”

(

7.34

,

7.35

).

The ringing phone drives his eyes back to the clerk

(

7.36

,

7.37

),

but he keeps Melanie in mind, too. A little before Louis notices, Max watches Melanie set off on her mission. Louis clumsily scans the shop, but Max is calm and purposeful. Each offscreen sound snaps his attention to what is crucial to the plan. After Melanie and Louis leave, it’s through Max’s eyes that we see Jackie’s departure, with the shopwoman calling, “Wait, your change!”

(

7.38

).

Max pauses, then heads for the fitting room to retrieve the shopping bag and the fortune.

7.34 After Jackie leaves for the changing room, Max shifts his attention to Melanie and Louis, in time to hear her say, “Hey, would you let go!”

7.35 His switch in attention is conveyed through a point-of-view shot. Compare

7.29

.

7.36 Max has been studying the couple, but the sound of a ringing phone offscreen makes him shift his glance.

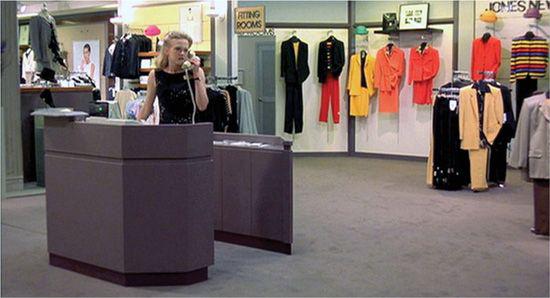

7.37 The clerk answers the phone. (Compare

7.31

). This diversion impels Melanie to seize the moment and stride into the changing room, watched by Max and, eventually, Louis.

7.38 After the bogus switch has been made, Jackie comes out and hurries to the counter. Max watches the transaction, and from his point of view we see Jackie rush off, with the clerk calling after, “Wait, your change!” Compare

7.25

. Now Max walks to the counter. His approach will be presented, in keeping with the rest of the sequence, as his optical point-of-view.

By repeating key actions, noises, and lines of dialogue, the replays lay out the mechanics of the exchange cogently. The variations between the second and third sequences allow Tarantino to characterize the thieves. Max is more alert than Louis and Melanie, and offscreen sounds prompt him to shift his attention precisely. Moreover, each version of story events is nested neatly inside the next one: Jackie and the clerk, then Jackie and the clerk watched by Melanie and Louis, then all the others watched by Max, who completes the money exchange. Sound and image work together to peel back each layer and expand our appreciation of Jackie’s intricate double-cross.

Rather than showing the cavalry riding to the rescue, the film’s narration uses offscreen sound to restrict our awareness to the initial despair of the passengers and their growing hope as they hear the distant sound. The sound of the bugle also emerges imperceptibly out of the nondiegetic music. Only Lucy’s line tells us that this is a diegetic sound that signals their rescue, at which point the narration becomes far less restricted.

Diegetic sound harbors other possibilities. Often a filmmaker uses sound to represent what a character is thinking. We hear the character’s voice speaking his or her thoughts even though that character’s lips do not move; presumably, other characters cannot hear these thoughts. Here the narration uses sound to achieve subjectivity, giving us information about the mental state of the character. Such spoken thoughts are comparable to mental images on the visual track. A character may also remember words, snatches of music, or events as represented by sound effects. In this case, the technique is comparable to a visual flashback.

The use of sound to enter a character’s mind is so common that we need to distinguish between internal and external diegetic sound.

External diegetic sound

is that which we as spectators take to have a physical source in the scene.

Internal diegetic sound

is that which comes from inside the mind of a character; it is subjective. Nondiegetic and internal diegetic sounds are often called

sound over

because they do not come from the real space of the scene. Internal diegetic sound can’t be heard by other characters.

In the Laurence Olivier version of

Hamlet,

for example, the filmmaker presents Hamlet’s famous soliloquies as interior monologues. Hamlet is the source of the thoughts we hear represented as speech, but the words are only in his mind, not in his objective surroundings. Gus Van Sant employs a similar tactic in

Paranoid Park.

A teenage boy fleeing from a horrific accident is plagued by inner voices, some of them auditory flashbacks. By having snatches of dialogue burst in from different stereo channels and with different degrees of clarity, Van Sant presents the boy as engulfed by confusion about what to do next.

David Lynch makes interior monologue a central device in

Dune,

in which nearly every major character is given passages of internal diegetic observations. These aren’t lengthy soliloquies but rather brief phrases slipped into pauses in normal conversation scenes. The result is an omniscient narration that unexpectedly plunges into mental subjectivity. The characters’ voiced thoughts sometimes inter-weave with the external dialogue so tightly that they create a running commentary on a scene’s action.

Recent films have reshaped the conventions of internal diegetic sound even more. Now an inner monologue may not be signaled by close shots of a character who’s thinking, as in

Hamlet

and

Dune.

Wong Kar-wai and Terrence Malick will sometimes inject a character’s voiced thoughts into scenes in which the character isn’t prominent, or even visible. As the voice of a paid killer reflects on his job in Wong’s

Fallen Angels,

we see distant shots of him mixed with several shots of the woman who arranges his contracts. In Malick’s

The Thin Red Line

and

The New World,

characters are heard musing during lengthy montage sequences in which they don’t even appear. These floating monologues come to resemble a more traditional voice-over narration. This impression is reinforced when the inner monologue uses the past tense, as if the action we’re seeing onscreen is being recalled from a later time.

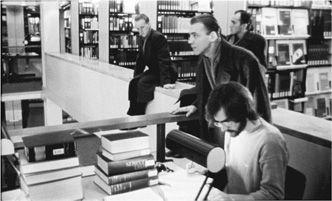

A different sort of internal diegetic sound occurs in Wim Wenders’s

Wings of Desire.

Dozens of people are reading in a large public library

(

7.44

).

Incidentally, this sequence also constitutes an interesting exception to the general rule that one character cannot hear another’s internal diegetic sound. The film’s premise is that Berlin is patrolled by invisible angels who

can

tune in to humans’ thoughts. This is a good example of how the conventions of a genre (here, the fantasy film) and the film’s specific narrative context can modify a traditional device.

7.44 As the camera tracks past the readers in

Wings of Desire,

we hear their thoughts as a throbbing murmur of many voices in many languages.