B0041VYHGW EBOK (122 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

Multichannel recording and reproduction tremendously increase the filmmaker’s ability to suggest sound perspective. In most 35mm theaters equipped with multitrack sound systems, three speakers are located behind the screen. The center speaker transmits most of the onscreen dialogue, as well as the most important effects and music. The left and right speakers are stereophonic, adding their sound effects, music, and minor dialogue. These channels can suggest a region of sound within the frame or just offscreen. Surround channels principally carry minor sound effects and some music, and they are divided among several speakers arranged along the sides and in the back of the theater. The “inner dialogue” shot in

Paranoid Park

is unusual in spreading more important dialogue to subsidiary channels.

“She first hears the music at a bit of a distance, coming from the house, and as she walks in—the music is getting closer, step-by-step—she goes from the entrance way up the stairs—the music is still growing—and she finally passes by a guitarist on the stairs.”

—Tony Volante, re-recording mixer,

Rachel Getting Married

By using stereophonic and surround tracks, a film can more strongly imply a sound’s distance and placement. In farcical comedies like

The Naked Gun

and

Hot Shots,

stereophonic sound can suggest collisions and falls outside the frame. Without the greater localization offered by the stereophonic channels, we might scan the frame for sources of the sounds. Even the center channel can be used to localize an offscreen object. In the climactic scene of

The Fugitive,

Richard Kimble is sneaking up on the friend who has betrayed him, and he reaches down past the lower frame line. As he slides his arm to the right, a rolling clank in the center track tells us that there is an iron pipe at his feet.

In addition, stereo reproduction can specify a moving sound’s direction. In David Lean’s

Lawrence of Arabia,

for instance, the approach of planes to bomb a camp is first suggested through a rumble occurring only on the right side of the screen. Lawrence and an officer look off right, and their dialogue identifies the source of the sound. Then, when the scene shifts to the besieged camp itself, the sound slides from channel to channel, suggesting the planes swooping overhead.

With stereophonic and surround channels, a remarkably convincing three-dimensional sound environment may be created within the theater. Sound sources can alter in position as the camera pans or tracks through a locale. The

Star Wars

series uses multiple-channel sound to suggest space vehicles whizzing not only across the screen but also above and behind the spectators.

Like other techniques, sound localization in the theater needn’t be used for realistic purposes.

Apocalypse Now

divides its six-track sound among three channels in the rear of the theater and three in the front. In the film’s first sequence, mentioned above, the protagonist Ben Willard is seen lying on his bed. Shots of his feverish face are superimposed on shots of U.S. helicopters dropping napalm on the Vietnamese jungle. The sound oscillates between internal and external status, as Willard’s mind turns the whoosh of a ceiling fan into the whir of helicopter blades. These subjective sounds issue from both the front and back of the theater, engulfing the audience.

Abruptly, a POV shot tracking toward the window suggests that Willard has gotten to his feet and is walking. As the camera moves, the noises fade from all rear speakers and become concentrated in the front ones at screen left, right, and center. Then, as Willard’s hand opens the venetian blinds to reveal his vision of the street outside, the sound fades out of the left and right front speakers and comes only from the center channel. Our attention has been narrowed: as we leave Willard’s mind, the sound steers us back to the outside world, which is rendered as unrealistically monophonic. In addition, the disparity in acoustic dimensions suggests that the protagonist’s wraparound memory of jungle destruction is more powerful than the pallid environment of Saigon.

Sound also permits the filmmaker to represent time in various ways. This is because the time represented on the sound track may or may not be the same as that represented in the image.

The most straightforward audio-visual relations involve sound–image synchronization. The matching of sound with image in projection creates

synchronous sound

. In that case, we hear the sound at the same time as we see the source produce the sound. Dialogue between characters is normally synchronized so that the lips of the actors move at the same time that we hear the appropriate words.

When the sound does go out of synchronization during a viewing (often through an error in projection or lab work), the result is quite distracting. But some filmmakers have obtained imaginative effects by putting

asynchronous,

or out-ofsync,

sound

into the film itself. One such effect occurs in a scene in the musical by Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen,

Singin’ in the Rain.

In the early days of Hollywood sound filming, a pair of silent screen actors have just made their first talking picture,

The Dueling Cavalier.

Their film company previews the film for an audience at a theater. In the earliest talkies, sound was often recorded on a phonograph disc to be played along with the film, and the sound sometimes fell out of synchronization with the picture. This is what happens in the preview of

The Dueling Cavalier.

As the film is projected, it slows down momentarily, but the record keeps running. From this point, all the sounds come several seconds before their sources are seen in the image. A line of dialogue begins,

then

the actor’s lips move. A woman’s voice is heard when a man moves his lips, and vice versa. The humor of this disastrous preview in

Singin’ in the Rain

depends on our realization that a film’s synchronization of sound and image is an illusion produced by mechanical means.

A lengthier play with our expectations about synchronization comes in Woody Allen’s

What’s Up, Tiger Lily?

Allen has taken an Asian spy film and dubbed a new sound track on, but the English-language dialogue is not a translation of the original. Instead, it creates a new story in comic juxtaposition with the original images. Much of the humor results from our constant awareness that the words are not perfectly synchronized with the actors’ lips. Allen has turned the usual problems of the dubbing of foreign films into the basis of his comedy.

Synchronization relates to screen duration, or

viewing

time. As we saw in

Chapter 3

, narrative films can also present

story

and

plot

time. To recall the distinction: story time consists of the order, duration, and frequency of all the events pertinent to the narrative, whether they are shown to us or not. Plot time consists of the order, duration, and frequency of the events actually represented in the film. Plot time shows us selected story events but skips over or only suggests others.

Story and plot time can be manipulated by sound in two principal ways. If the sound takes place at the same time as the image in terms of the story events, it is

simultaneous sound

. This is overwhelmingly the most common usage. When characters speak onscreen, the words we hear are occurring at the same moment in the plot’s action as in story time.

But it is possible for the sound we hear to occur earlier or later in the story than the events we see in the image. In this manipulation of story order, the sound becomes

nonsimultaneous.

The most common example of this is the sonic flashback. For instance, we might see a character onscreen in the present but hear another character’s voice from an earlier scene. By means of nonsimultaneous sound, the film can give us information about story events without presenting them visually. And nonsimultaneous sound may, like simultaneous sound, have either an external or an internal source—that is, a source in the objective world of film or the subjective realms of the character’s mind.

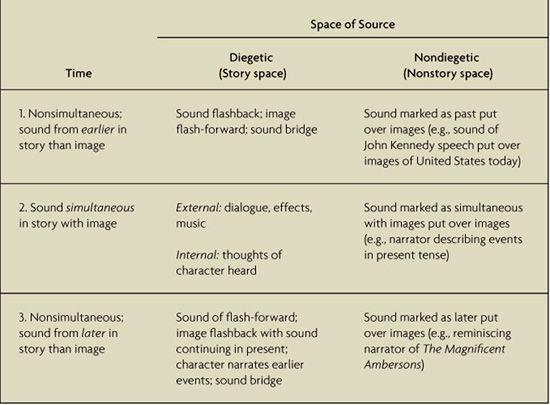

So temporal relationships in the cinema can get complicated. To help distinguish them,

Table 7.2

sums up the possible temporal and spatial relationships that image and sound can display.

TABLE 7.2 Temporal Relations of Sound in Cinema

Because the first and third of these possibilities are rare, we start by commenting on the second, most common, option:

2.

Sound simultaneous in story with image.

This is by far the most common temporal relation that sound has in fiction films. Noise, music, or speech that comes from the space of the story almost invariably occurs at the same time as the image. Like any other sort of diegetic sound, simultaneous sound can be either external (objective) or internal (subjective).

1.

Sound earlier in story than image.

Here the sound comes from an earlier point in the story than the action currently visible onscreen. A clear example occurs at the end of Joseph Losey’s

Accident.

Over a shot of a driveway gate, we hear a car crash. The sound represents the crash that occurred at the

beginning

of the film. Now if there were cues that the sound was internal—that is, that a character was recalling it—it would not strictly be coming from the past, since the

memory

of the sound would be occurring in the present. Late in

The Sixth Sense,

for example, the protagonist recalls a crucial statement that his young patient had made to him, causing him to realize something that casts most of the previous action in an entirely new light. The boy’s voice is clearly coming from the protagonist’s mind at the moment of his recollection. But in the scene from

Accident,

no character is remembering the scene, so we have a fairly pure case of a sonic flashback. In this film, an unrestricted narration makes an ironic final comment on the action.

Sound may belong to an earlier time than the image in another way. The sound from the previous scene may linger briefly while the image is already presenting the next scene. This common device is called a

sound bridge

. Sound bridges of this sort may create smooth transitions by setting up expectations that are quickly confirmed, as in a scene change in Jonathan Demme’s

The Silence of the Lambs

(

7.50

,

7.51

).

Sound bridges can also make our expectations more uncertain. In Tim Hunter’s

The River’s Edge,

three high-school boys are standing outside school, and one of them confesses to having killed his girlfriend. When his pals scoff, he says, “They don’t believe me.” There is a cut to the dead girl lying in the grass by the river, while on the sound track we hear one of his friends respond to him by calling it a crazy story that no one will believe. For an instant, we cannot be sure whether a new scene is starting or we are seeing a cutaway to the corpse, which could be followed by a shot returning to the three boys at school. But the shot dwells on the dead girl, and after a pause, we hear, with a different sound ambience, “If you brought us …” Then there is a cut to a shot of the three youths walking through the woods to the river, as the same character continues, “… all the way out here for nothing….” The friend’s remark about the crazy story belongs to an earlier time than the shot of the corpse, and it is used as an unsettling sound bridge to the new scene.

3.

Sound later in story than image.

Nonsimultaneous sound may also occur at a time later than that depicted by the images. Here we are to take the images as occurring in the past and the sound as occurring in the present or future.

A simple prototype occurs in many trial dramas. The testimony of a witness in the present is heard on the sound track, while the image presents a flashback to an earlier event. The same effect occurs when the film employs a reminiscing narrator, as in John Ford’s

How Green Was My Valley.

Aside from a glimpse at the beginning, we do not see the protagonist Huw as a man, only as a boy, but his narration accompanies the bulk of the plot, which is set in the distant past. Huw’s present-time voice on the sound track creates a strong sense of nostalgia for the past and constantly reminds us of the pathetic decline that the characters will eventually suffer.

Since the late 1960s, it has become somewhat common for the sound from the next scene to begin while the images of the last one are still on the screen. Like the instances mentioned above, this transitional device is a s

ound bridge.

In Wim Wenders’s

American Friend,

a nighttime shot of a little boy riding in the back seat of a car is accompanied by a harsh clacking. There is a cut to a railroad station, where the timetable board flips through its metal cards listing times and destinations. Since the sound over the shot of the boy comes from the later scene, this portion is nonsimultaneous.