B0041VYHGW EBOK (16 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

In the United States, theater owners bid for each film a distributor releases, and in most states, they must be allowed to see the film before bidding. Elsewhere in the world, distributors may force exhibitors to rent a film without seeing it (called

blind booking

), perhaps even before it has been completed. Exhibitors may also be pressured to rent a package of films in order to get a few desirable items (

block booking

).

Once the exhibitor has contracted to screen the film, the distributor can demand stiff terms. The theater keeps a surprisingly small percentage of total box office receipts (known as the

gross

or

grosses

). One standard arrangement guarantees the distributor a minimum of 90 percent of the first week’s gross, dropping gradually to 30 percent after several weeks. These terms aren’t favorable to the exhibitor. A failure that closes quickly will yield almost nothing to the theater, and even a successful film will make most of its money in the first two or three weeks of release, when the exhibitor gets less of the revenue. Averaged out, a long-running success will yield no more than 50 percent of the gross to the theater. To make up for this drawback, the distributor allows the exhibitor to deduct from the gross the expenses of running the theater (a negotiated figure called the

house nut

). In addition, the exhibitor gets all the cash from the concession stand, which may deliver up to 70 percent of the theater’s profits. Without high-priced snacks, movie houses couldn’t survive.

“Selling food is my job. I just happen to work in a theater.”

— Theater manager in upstate New York

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

Every Monday, the weekend boxoffice figures are news, but what do they mean? We add some nuance in “What won the weekend? or how to understand box-office figures.”

Once the grosses are split with the exhibitor, the distributor receives its share (the

rentals

) and divides it further. A major U.S. distributor typically takes 35 percent of the rentals as its distribution fee. If the distributor helped finance the film, it takes another percentage off the top. The costs of prints and advertising are deducted as well. What remains comes back to the filmmakers. Out of the proceeds, the producer must pay all

profit participants

—the directors, actors, executives, and investors who have negotiated a share of the rental returns.

For most films, the amount returned to the production company is relatively small. Once the salaried workers have been paid, the producer and other major players usually must wait to receive their share from video and other ancillary markets. Because of this delay, and the suspicion that the major distributors practice misleading accounting, powerful actors and directors may demand “first-dollar” participation, meaning that their share will derive from the earliest money the picture returns to the distributor.

The major distributors all belong to multinational corporations devoted to leisure activities. For example, Time Warner owns Warner Bros., which produces and distributes films while also controlling subsidiary companies New Line Cinema, Picturehouse, and Warner Independent Pictures. In addition, Time Warner owns the Internet provider America On Line. The conglomerate owns broadcast and cable services such as CNN, HBO, and the Cartoon Network; publishing houses and magazines (

Time, Life, Sports Illustrated, People,

and DC Comics); music companies (Atlantic, Elektra); theme parks (Six Flags); and sports teams (the Atlanta Braves and the Atlanta Hawks). Since distribution firms are constantly acquiring and spinning off companies, the overall picture can change unexpectedly. In late 2005, for instance, DreamWorks SKG, a production company that was strongly aligned with Universal, was purchased by Paramount. In 2008, Dream Works announced that it was leaving Paramount to become an independent company distributing through Universal, before abruptly revealing in early 2009 that its distribution partner would instead be Disney.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

One example of how such a change affects the rest of the industry is discussed in our entry on the absorption of New Line Cinema into Warner Bros. in 2008—“Filling the New Line gap.”

Independent and overseas filmmakers usually don’t have access to direct funding from major distribution companies, so they try to presell distribution rights in order to finance production. Once the film is finished, they try to attract distributors’ attention at film festivals. In 2005, after strong reviews at the Cannes Film Festival, Woody Allen’s

Match Point

was picked up for U.S. distribution by Dream Works SKG. In the same year, the South African production

Tsotsi

won the People’s Choice Award at the Toronto International Film Festival, and its North American rights were bought by Buena Vista.

Specialized distributors, such as the New York firms Kino and Milestone, acquire rights to foreign and independent films for rental to art cinemas, colleges, and museums. As the audience for these films grew during the 1990s, major distributors sought to enter this market. The independent firm Miramax generated enough low-budget hits to be purchased by the Disney corporation. With the benefit of Disney’s funding and wider distribution reach, Miramax movies such as

Pulp Fiction, Scream, Shakespeare in Love,

and

Hero

earned even bigger box-office receipts. Sony Pictures Classics funded art house fare that sometimes crossed over to the multiplexes, as

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

did. More recently, Fox Searchlight released a film that Warner Bros. had turned down, and it achieved popular and critical success with

Slumdog Millionaire.

By belonging to multinational conglomerates, film distributors gain access to bank financing, stock issues, and other sources of funding. Branch offices in major countries can carry a film into worldwide markets. Sony’s global reach allowed it to release 11 different sound track CDs for

Spider-Man 2,

each one featuring artists familiar in local territories. Just as important, media conglomerates can build

synergy

—the coordination of sectors within the company around a single piece of content, usually one that is “branded.”

Batman

and

The X-Files

are famous instances of how the film, television, publishing, and music wings of a firm can reinforce one another. Every product promotes the others, and each wing of the parent company gets a bit of the business. One film can even advertise another within its story

(

1.40

).

Although synergy sometimes fails, multimedia giants are in the best position to take advantage of it.

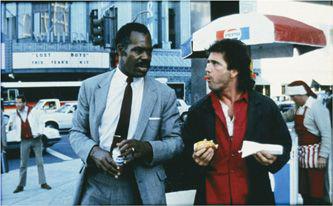

1.40 In

Lethal Weapon,

as Murtaugh and Riggs leave a hotdog stand, they pass in front of a movie theater advertising

The Lost Boys,

another Warner Bros. film (released four months after

Lethal Weapon

). The prominence of Pepsi-Cola in this shot is an example of

product placement

—featuring well-known brands in a film in exchange for payment or cross-promotional services.

“Our underlying philosophy is that all media are one.”

— Rupert Murdoch, owner of News Corp. and Twentieth Century Fox

Distributors arrange release dates, make prints, and launch advertising campaigns. For big companies, distribution can be efficient because the costs can be spread out over many units. One poster design can be used in several markets, and a distributor who orders a thousand prints from a laboratory will pay less per print than the filmmaker who orders one. Large companies are also in the best position to cope with the rise of distribution costs. Today, the average Hollywood film is estimated to cost around $70.8 million to make and an additional $35.9 million to distribute.

The risky nature of mass-market filmmaking has led the majors to two distribution strategies:

platforming

and

wide release.

With platforming, the film opens first in a few big cities. It’s then gradually expanded to theaters around the country, though it may never play in every community. If the strategy is successful, anticipation for the film builds, and it remains a point of discussion for months. The major distributors tend to use platforming for unusual films, such as

Munich

and

Brokeback Mountain,

which need time to accumulate critical support and generate positive word-of-mouth. Smaller distributors use platforming out of necessity, since they can’t afford to make enough prints to open wide, but the gradual accumulation of buzz can work in their favor, too.

In wide release, a film opens at the same time in many cities and towns. In the United States, this requires that thousands of prints be made, so wide release is available only to the deep-pocketed major distributors. Wide release is the typical strategy for mainstream films, with two or three new titles opening each weekend on 2000–4000 screens. A film in wide release may be a midbudget one—a comedy, an action picture, a horror or science fiction film, or a children’s animated movie. It may also be a very big-budget item, a

tentpole

picture such as

War of the Worlds

or the latest Harry Potter installment.

Distributors hope that a wide opening signals a “must-see” film, the latest big thing. Just as important, opening wide helps recoup costs faster, since the distributor gets a larger portion of box office receipts early in the run. But it’s a gamble. If a film fails in its first weekend, it almost never recovers momentum and can lose money very quickly. Even successful films usually lose revenues by 40 percent or more every week they run. So when two high-budget films open wide the same weekend, the competition is harmful to all. Companies tend to plan their tentpole release dates to avoid head-to-head conflict. On the weekend in May 2005 when the final installment of Fox’s

Star Wars

saga opened on nearly 3700 U.S. screens, other distributors offered no wide releases at all.

Episode III—Revenge of the Sith

grossed nearly $160 million in four days.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

With help from some colleagues, we examine the recent phenomenon of movie franchises and defend the idea in “Live with it! There’ll always be movie sequels. Good thing, too.”

Wide releasing has extended across the world. As video piracy spread, distribution companies realized the risks of opening wide in the United States and then waiting weeks or months before opening overseas. By then, illegal DVDs and Internet downloads would be available. As a result, U.S. companies have begun experimenting with

day-and-date

releasing for their biggest tentpole pictures.

Matrix: Revolutions

opened simultaneously on 8000 screens in the United States and 10,000 screens in 107 other countries. In a stroke of showmanship, the first screening was synchronized to start at the same minute across all time zones.

The distributor provides not only the movie but a publicity campaign. The theater is supplied with a

trailer,

a short preview of the upcoming film. Many executives believe that a trailer is the single most effective piece of advertising. Shown in theaters, it gets the attention of confirmed moviegoers. Posted on an official movie website, YouTube, and many fan sites, a trailer gains mass viewership.

Publicists run press junkets, flying entertainment reporters to interview the stars and principal filmmakers on-set or in hotels. “Infotainment” coverage in print and broadcast media or online build audience awareness. A “making of” documentary, commissioned by the studio, may be shown on cable channels. A prominent film’s premiere creates an occasion for further press coverage

(

1.41

).

For journalists, the distributor provides electronic press kits (EPKs), complete with photos, background information, star interviews, and clips of key scenes. Even a modestly budgeted production such as

Waiting to Exhale

had heavy promotion: five separate music videos, star visits to Oprah Winfrey, and displays in thousands of bookstores and beauty salons.

My Big Fat Greek Wedding

cost $5 million to produce, but the distributors spent over $10 million publicizing it.

1.41 A press conference held at Te Papa Museum in Wellington, New Zealand, as part of the December 1, 2003, world premiere of

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King.