B0041VYHGW EBOK (195 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

12.49

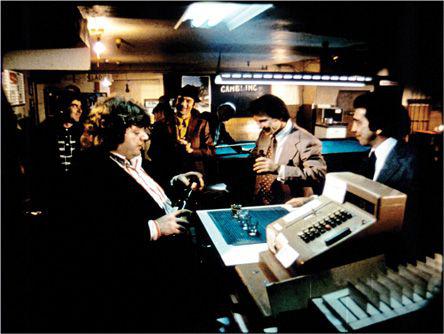

Mean Streets

: Scorsese uses depth staging and deep focus for the famous “Mook” confrontation.

Since movies had been a major part of the young directors’ lives, many films of the New Hollywood were based on the old Hollywood. De Palma’s films borrowed heavily from Hitchcock, with

Dressed to Kill

(1980) an overt redoing of

Psycho.

Peter Bogdanovich’s

What’s Up, Doc?

(1972) was an updating of screwball comedy, with particular reference to Howard Hawks’s

Bringing Up Baby.

Carpenter’s

Assault on Precinct 13

(1976) derived partly from Hawks’s

Rio Bravo;

the editing is credited to “John T. Chance,” the character played by John Wayne in Hawks’s Western.

At the same time, many directors admired the European tradition, with Scorsese drawn to the visual splendor of Luchino Visconti and British director Michael Powell. Some directors dreamed of making complex art films in the European mold. The best-known effort is probably Coppola’s

The Conversation

(1974), a mysterystory reworking of Antonioni’s

Blow-Up

(1966) that plays ambiguously between reality and hallucination (

p. 177

).

“I love the idea of not being an independent filmmaker. I’ve liked working within the system. And I’ve admired a lot of the older directors who were sort of ‘directors for hire.’ Like Victor Fleming was in a contract all those years to Metro and Selznick and Mayer … he made

Captains Courageous.

And you know, his most famous films:

Wizard of Oz

and

Gone with the Wind.

”— Steven Spielberg, producer/director

Robert Altman and Woody Allen, in quite different ways, displayed creative attitudes fed by European cinema. Altman’s

Three Women

(1977) and Allen’s

Interiors

(1978), for example, owed a good deal to Ingmar Bergman’s work. More influential were their innovations on other fronts. Allen revived the American comedy of manners in

Annie Hall

(1977),

Manhattan

(1979), and

Hannah and Her Sisters

(1985). Altman’s

McCabe and Mrs. Miller

(1971) and

The Long Goodbye

(1973) displayed rough-edged performances, dense soundtracks, and a disrespectful approach to genre. His

Nashville

(1975) built its plot out of the casual encounters among two dozen characters, none of whom is singled out as the protagonist. Altman explored this narrative form throughout his career, notably in

A Wedding

(1978),

Short Cuts

(1993), and

A Prairie Home Companion

(2006). Such networkbased plotting became a common option for independent films such as

Magnolia

(1999),

Crash

(2005), and

Me and You and Everyone We Know

(2005).

Altman and Allen were of a slightly older generation, but many movie brats proved to be the most continuously successful directors of the era. Lucas and Spielberg became powerful producers, working together on the Indiana Jones series and personifying Hollywood’s new generation. Coppola failed to sustain his own studio, but he remained an important director. Scorsese’s reputation rose steadily: By the end of the 1980s, he was the most critically acclaimed living American filmmaker.

During the 1980s, fresh talents won recognition, creating a New New Hollywood. Many of the biggest hits of the decade continued to come from Lucas and Spielberg, but other, somewhat younger directors were successful too: James Cameron (

The Terminator,

1984;

Terminator 2: Judgment Day,

1991), Tim Burton (

Beetlejuice,

1988;

Batman,

1989), and Robert Zemeckis (

Back to the Future,

1985;

Who Framed Roger Rabbit,

1988). Many of the successful films of the 1990s came from directors from both these successive waves of the Hollywood renaissance: Spielberg’s

Jurassic Park

(1993), De Palma’s

Mission: Impossible

(1996), and Lucas’s

The Phantom Empire

(1999), as well as Zemeckis’s

Forrest Gump

(1994), Cameron’s

Titanic

(1997), and Burton’s

Sleepy Hollow

(1999).

The resurgence of mainstream film was also fed by filmmakers from outside Hollywood. Many directors came from abroad—from Britain (Tony and Ridley Scott), Australia (Peter Weir, Fred Schepisi), Germany (Wolfgang Peterson), the Netherlands (Paul Verhoeven), and Finland (Rennie Harlin). During the 1980s and 1990s, more women filmmakers also became commercially successful, such as Amy Heckerling (

Fast Times at Ridgemont High,

1982;

Look Who’s Talking,

1990), Martha Coolidge (

Valley Girl,

1983;

Rambling Rose,

1991), and Penelope Spheeris (

Wayne’s World,

1992).

Several directors from independent film managed to shift into the mainstream, making medium-budget pictures with widely known stars. David Lynch moved from the midnight movie

Eraserhead

(1978) to the cult classic

Blue Velvet

(1986), while Canadian David Cronenberg, a specialist in low-budget horror films such as

Shivers

(1975), won wider recognition with

The Dead Zone

(1983;

12.50

) and

The Fly

(1986). The New New Hollywood also absorbed some minority directors from independent film. Wayne Wang was the most successful Asian American filmmaker (

Chan Is Missing,

1982;

Smoke,

1995). Spike Lee (

She’s Gotta Have It,

1986;

Malcolm X,

1992) led the way for young African-American directors such as Reginald Hudlin (

House Party,

1990), John Singleton (

Boyz N the Hood,

1991), Mario van Peebles (

New Jack City,

1991), and Allen and Albert Hughes (

Menace II Society,

1993).

12.50

The Dead Zone

: the hero, a psychic possessed by visions of future events, imagines a fire.

Still other directors remained independent and more or less marginal to the studios. In

Stranger Than Paradise

(1984) and

Down by Law

(1986), Jim Jarmusch presented quirky, decentered narratives peopled by drifting losers

(

12.51

).

Allison Anders treated the contemporary experiences of disaffected young women, either in small towns (

Gas Food Lodging,

1992) or city centers (

Mi Vida Loca,

1994). Leslie Harris’s

Just Another Girl on the IRT

(1994; 1.34) likewise focused on the problems of urban women of color.

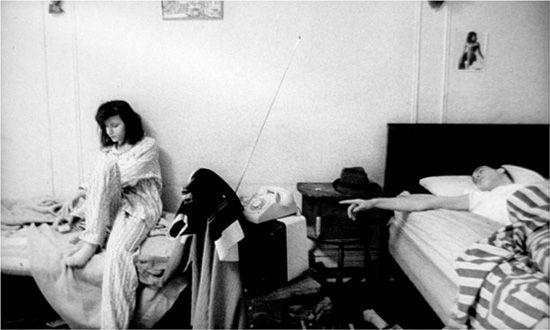

12.51 Eva and Willie, the listless protagonists of

Stranger Than Paradise.

“These characters,” Jarmusch explains, “move through the world of the film in a kind of random, aimless way, like looking for the next card game or something.”

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

We take a look back at the fall 1994 season and ask whether Hollywood filmmaking has really changed all that much since in “Fantasy franchises, or franchise fantasies?”

Stylistically, no single coherent film movement emerged during the 1970s and 1980s. The most mainstream of the young directors continued the tradition of classical American cinema. Continuity editing remained the norm, with clear signals for time shifts and new plot developments. Some directors embellished Hollywood’s traditional storytelling strategies with new or revived visual techniques. In films from

Jaws

onward, Spielberg used deep-focus techniques reminiscent of

Citizen Kane

(5.39, 12.52). Lucas developed motion-control techniques for filming miniatures for

Star Wars,

and his firm Industrial Light and Magic (ILM) became the leader in new special-effects technology. Spielberg and Lucas also led the move toward digital sound and high-quality theater reproduction technology.

12.52 In

Jurassic Park

Spielberg harks back to Orson Welles’s use of depth compositions.

Less well funded Hollywood filmmaking cultivated more flamboyant styles. Scorsese’s

Taxi Driver, Raging Bull

(

pp. 438

–442), and

The Age of Innocence

(1993) use camera movement and slow motion to extend the emotional impact of a scene. De Palma has been an even more outrageous stylist; his films flaunt long takes, startling overhead compositions, and split-screen devices. Coppola experimented with fast-motion black-and-white in

Rumble Fish

(1983), phone conversations handled in the foreground and background of a single shot (

Tucker,

1988), and old-fashioned special effects to lend a period mood to

Bram Stoker’s Dracula

(1993).

Several of the newer entrants into Hollywood enriched mainstream conventions of genre, narrative, and style. We have already seen one example of this strategy in our discussion of Spike Lee’s

Do The Right Thing

(

pp. 404

–408). Another intriguing example is Wayne Wang’s

The Joy Luck Club

(1993;

12.53

). Set among Chinese American families, the film concentrates on four emigrant mothers and their four assimilated daughters. In presenting the women’s lives, the film adheres to narrative principles that recall

Citizen Kane.

At a party, the three surviving mothers recall their lives before coming to America, and a lengthy flashback is devoted to each one. Alongside each mother’s flashback, however, the plot sets flashbacks tracing the experiences of each woman’s daughter in the United States. The result is a rich set of dramatic and thematic parallels. Sometimes the mother–daughter juxtapositions create sharp contrasts; at other times, they blend together to emphasize commonalities across generations. The women’s voice-over commentaries always orient the viewer to the shifts in narration while still enabling Wang and his screenwriters to treat the flashback convention in ways that intensify the emotional effect.