B0041VYHGW EBOK (196 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

12.53

The Joy Luck Club.

A similar effort to revise conventions pervades the work of other independent directors. The brothers Joel and Ethan Coen treat each film as a pretext for exploring cinema’s expressive resources. In

Raising Arizona

(1987), high-speed tracking shots combine with distorting wide-angle close-ups to create comic-book exaggerations

(

12.54

).

A somewhat similar approach is taken in Gregg Araki’s gay road picture

The Living End

(1992). In films such as

Trust

(1991), Hal Hartley mutes a melodramatic plot through slow pacing, brooding close-ups, and dynamic foreground/background compositions

(

12.55

).

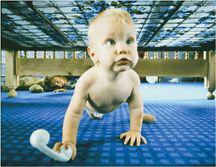

12.54 Wide-angle tracking shots follow crawling babies along the floor and under furniture in

Raising Arizona.

12.55 In

Trust,

a melodramatic scene between mother and daughter is intensified through deep-space staging and a tight close-up.

Independent directors of the 1980s and 1990s have also experimented with narrative construction. The Coens’

Barton Fink

(1991) passes unnoticeably from a satiric portrait of 1930s Hollywood into a hallucinatory fantasy. Quentin Tarantino’s

Reservoir Dogs

(1993) and

Pulp Fiction

(1994) juggle story and plot time in ways that recall the complex flashbacks of the 1940s. Unlike the flashbacks in

The Joy Luck Club,

moreover, the switches are not motivated as characters’ memories; the audience is forced to puzzle out the purposes served by the time shifts. In

Daughters of the Dust

(1991), Julie Dash incorporates the rich Gullah dialect and explores a complex time scheme that seeks to fuse present and future. In one scene, optical effects give the characters a glimpse of a child who is as yet unborn.

In the 1980s and 1990s, while younger studio directors adapted classical conventions to modern tastes, an energetic independent film tradition began pushing the envelope. By the 2000s, the two trends were merging in surprising ways. As independent films began to win larger audiences, major studios eagerly acquired distribution companies such as Miramax and October Films. Much media journalism fostered the impression that Hollywood was becoming subverted by independent filmmaking, but in fact, more and more, the major studios controlled audiences’ access to formerly independent productions. The Sundance Film Festival, founded as a forum for the off-Hollywood scene, came to be treated as a talent market by the studios, which often bought films in order to line up the filmmaker for more mainstream projects. Thus after Kevin Smith found success with

Clerks

(1994), he directed

Mallrats

(1995), a tame twenty-something comedy for Universal. Robert Rodriguez’s similarly microbudgeted

El Mariachi

(1992) proved a hit, so he was hired to remake it as an all-out action picture starring Antonio Banderas (

Desperado,

1995).

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

Some independent filmmakers use sensationalism to call attention to their work. See “Visionary Outlaw Mavericks on the dark edge; or, Indie Guignol,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=339

.

Yet sometimes the big-budget films of independent filmmakers conveyed a distinctly experimental attitude. Kevin Smith used the star-filled

Dogma

(1999) to question Catholic doctrine. David O. Russell, who had worked his way into the system with off-kilter comedies (

Spanking the Monkey,

1994;

Flirting with Disaster,

1996), made

Three Kings

(1999), an action picture that criticized Gulf War policies and that reveled in a flamboyant, digital-era style. Following in the path of

Pulp Fiction,

studio pictures began to play more boldly with narrative form. A genre thriller such as

The Sixth Sense

(1999) encouraged viewers to see it twice in order to detect how the narration had misled them. Stories might be told through complicated flashbacks, as in Steven Soderbergh’s

The Limey

(12.56). (See also box,

pp. 87

–89.) A film might reveal that one character was the imaginary creation of another (

Fight Club,

1999), or that a person could crawl into another’s brain (

Being John Malkovich,

1999), or that the external world was merely an illusion produced by sophisticated software (

The Matrix,

1999) or a novelist (

Stranger than Fiction

). In their willingness to experiment with ambiguous and teasing modes of narration, many American studio films began rivaling their overseas counterparts such as

Breaking the Waves

(1996),

Sliding Doors

(1998), and

Run Lola Run

(1998).

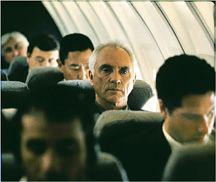

12.56 An ambiguous image that recurs throughout

The Limey:

it may be construed either as a flashback to the protagonist’s trip to the United States or as a flash-forward to his trip back to Britain, presented in the final scene.

At the start of the new century, many of the most thrilling Hollywood films were being created by a robust new generation, born in the 1960s and 1970s and brought up on videotape, video games, and the Internet. Like their predecessors, these directors were reshaping the formal and stylistic conventions of the classical cinema while also making their innovations accessible to a broad audience.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

For a discussion of director James Mangold and his relationship to the traditions of classical Hollywood filmmaking, see “Legacies,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=1261

.

While the New Hollywood directors were revamping American films, a young generation of directors in Hong Kong found footing in their industry and recast its traditional genres and creative methods. The result was not a unified film movement, but a local cinema with a robust identity. Hong Kong’s innovations in cinematic style and storytelling vigorously influenced world filmmaking well into the twentyfirst century.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

Why do some filmmakers take such a long time between movies? We explore some possible reasons in “Running on almost empty.”

Hong Kong produced films in the silent era and during the 1930s, although World War II halted production. When the industry revived in the 1950s, the most powerful studio was Shaw Brothers. Shaws owned theaters throughout East Asia and used Hong Kong as a production base for films in several languages, chiefly Mandarin Chinese. Shaws made films in many genres, but among its biggest successes were dynamic, gory swordfighting films (

wuxia pian,

or “tales of martial chivalry”). In the 1970s, another studio, Golden Harvest, triumphed with kung-fu films starring Bruce Lee. Although Lee completed only four martial-arts films before his death in 1973, he brought Hong Kong cinema to worldwide attention and forever identified it with films of acrobatic and violent action.

Several major directors worked in this period. Most famous is King Hu, who started as a Shaws director. In films like

Dragon Gate Inn

(1967) and

The Valiant Ones

(1975; 5.69), Hu reinvigorated the

wuxia pian

through graceful airborne swordplay and inventive cutting. Chang Cheh, another Shaws director, turned the swordplay film toward violent male melodrama (such as

The One-Armed Swordsman,

1967) before specializing in flamboyant kung-fu films such as

Crippled Avengers

(also called

Mortal Combat,

1978). Neither King Hu nor Chang Cheh was a practitioner of martial arts, but Lau Kar-leung was a fight choreographer before becoming a full-fledged director. Lau created a string of inventive films (such as

36th Chamber of Shaolin,

1978, and

The Eight-Diagram Pole Fighter,

1983) that showcased a range of dazzling marital-arts techniques.

By the early 1980s, traditional kung-fu was fading in popularity, and Shaws turned from moviemaking to its lucrative television business. At the same time, a new generation of directors came forward. One group had little formal education but had grown up in the film industry, working as stuntmen and martial artists. Among those who became directors were choreographers Yuen Wo-ping and Yuen Kuei (

Yes, Madam!,

1985). Sammo Hung choreographed, directed, and starred in many lively action films (such as

Eastern Condors,

1987).

The most famous graduate of the studio system was Jackie Chan, who labored as a copy of Bruce Lee before finding his feet in comic kung-fu. With

Drunken Master

(1978, directed by Yuen Wo-ping), he became a star throughout Asia and gained the power to direct his own films. In the early 1980s, Chan and his colleagues realized that kung-fu could be incorporated into Hollywoodish actionadventure movies. Chan made the historical adventure

Project A

(1983, also starring Hung) and the contemporary cop drama

Police Story

(1985). These and others were huge hits across Asia, partly because of Chan’s lovably goofy star persona, and partly because of his ingenious and dangerous action scenes (6.47–6.49).

Another group of directors had more formal training, with many attending film schools in the United States or Britain. When Ann Hui, Allen Fong, and others returned to Hong Kong, they found work in television before moving on to feature filmmaking. For a time, they constituted a local art cinema, attracting attention at festivals with such films as Hui’s

Boat People

(1982). But most of this group gravitated toward independent companies turning out comedies, dramas, and action films. Tsui Hark was the leader of this trend. As both director and producer, Tsui revived and reworked a range of genres: swordplay fantasy (

Zu: Warriors of the Magic Mountain,

1979), romantic comedy (

Shanghai Blues,

1984), historical adventure (

Peking Opera Blues,

1986;

12.57

), supernatural romance (

A Chinese Ghost Story,

1987, directed by Ching Siu-tung), and classic kung-fu (

Once upon a Time in China,

1990).