B0041VYHGW EBOK (43 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

We are still seeking to understand the principles by which a film is put together.

Chapter 2

showed that the concept of film form offers a way to do this.

Chapter 3

examined how films can be organized by narrative form, and later we’ll see that other types of form are often used in documentaries and experimental films.

When we see a film, though, we do not engage only with its form. We experience a

film

—not a painting or a novel. Analyzing a painting demands a knowledge of color, shape, and composition; analyzing a novel demands knowledge of language. To understand form in any art, we must be familiar with the medium that art utilizes. Consequently, our understanding of a film must also include features of the

film medium

.

Part Three

of this book investigates just this area. We shall look at four cinematic techniques: two techniques of the shot, mise-en-scene and cinematography; the technique that relates shot to shot, editing; and the relation of sound to film images.

Each chapter will introduce a single technique, surveying the choices it offers to the filmmaker. We’ll suggest how you can recognize the technique and its uses. Most important, we’ll concentrate on the functions of each technique. We’ll try to answer such questions as these: How may a technique guide expectations or furnish motifs for the film? How may it develop across a film? How may it direct our attention, clarify or emphasize meanings, and shape our emotional response?

In

Part Three

, we will also discover that in any film, certain techniques tend to create a formal system of their own. Every film develops specific techniques in patterned ways. This unified, developed, and significant use of particular technical choices we will call style. In our study of certain films, we’ll see how each filmmaker creates a distinctive stylistic system.

The use a film makes of the medium—the film’s style—cannot be studied apart from the film’s overall form. We will find that film style interacts with the formal system. In a narrative film, techniques can function to advance the cause–effect chain, create parallels, manipulate story–plot relations, or sustain the narration’s flow of information. But some uses of film technique can call attention to patterns of style. In either event, the chapters that follow will continually return to the problem of relations between a film’s overall form and its style.

Of all the techniques of cinema,

mise-en-scene

is the one with which we are most familiar. After seeing a film, we may not recall the cutting or the camera movements, the dissolves or the offscreen sound. But we do remember the costumes in

Gone with the Wind

and the bleak, chilly lighting in Charles Foster Kane’s Xanadu. We retain vivid impressions of the misty streets in

The Big Sleep

and the labyrinthine, fluorescent-lit lair of Buffalo Bill in

The Silence of the Lambs.

We recall Harpo Marx clambering over Edgar Kennedy’s peanut wagon (

Duck Soup

), Katharine Hepburn defiantly splintering Cary Grant’s golf clubs (

The Philadelphia Story

), and Michael J. Fox escaping high-school bullies on an improvised skateboard (

Back to the Future

). In short, many of our most sharply etched memories of the cinema turn out to center on mise-en-scene.

In the original French,

mise en scène

(pronounced meez-ahn-sen) means “putting into the scene,” and it was first applied to the practice of directing plays. Film scholars, extending the term to film direction, use the term to signify the director’s control over what appears in the film frame. As you would expect, mise-en-scene includes those aspects of film that overlap with the art of the theater: setting, lighting, costume, and the behavior of the figures. In controlling the mise-en-scene, the director

stages the event

for the camera.

Mise-en-scene usually involves some planning, but the filmmaker may be open to unplanned events as well. An actor may add a line on the set, or an unexpected change in lighting may enhance a dramatic effect. While filming a cavalry procession through Monument Valley for

She Wore a Yellow Ribbon,

John Ford took advantage of an approaching lightning storm to create a dramatic backdrop for the action

(

4.1

).

The storm remains part of the film’s mise-en-scene even though Ford neither planned it nor controlled it; it was a lucky accident that helped create one of the film’s most affecting passages. Jean Renoir, Robert Altman, and other directors have allowed their actors to improvise their performances, making the films’ mise-en-scene more spontaneous and unpredictable.

4.1

She Wore a Yellow Ribbon:

a thunderstorm in Monument Valley.

Before we analyze mise-en-scene in detail, one preconception must be brought to light. Just as viewers often remember this or that bit of mise-en-scene from a film, so they often judge mise-en-scene by standards of realism. A car may seem to be realistic for the period the film depicts, or a gesture may not seem realistic because “real people don’t act that way.”

Realism as a standard of value, however, raises several problems. Notions of realism vary across cultures, over time, and even among individuals. Marlon Brando’s acclaimed realist performance in the 1954 film

On the Waterfront

looks stylized today. American critics of the 1910s praised William S. Hart’s Westerns for being realistic, but equally enthusiastic French critics of the 1920s considered the same films to be as artificial as a medieval epic. Most important, to insist rigidly on realism for all films can blind us to the vast range of mise-en-scene possibilities.

Look, for instance, at the frame from

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

(

4.2

).

Such a depiction of rooftops certainly does not accord with our conception of normal reality. Yet to condemn the film for lacking realism would be inappropriate, because the film uses stylization to present a madman’s fantasy.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

borrows conventions of Expressionist painting and theater, and then assigns them the function of suggesting a delusion.

4.2 An Expressionist rooftop scene created from jagged peaks and slanted chimneys in

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

It is best, then, to examine the

functions

of mise-en-scene in the films we see. While one film might use mise-en-scene to create an impression of realism, other films might seek very different effects: comic exaggeration, supernatural terror, understated beauty, and any number of other functions. We should analyze miseen-scene’s function in the total film—how it is motivated, how it varies or develops, how it works in relation to other film techniques.

Confining the cinema to some notion of realism would impoverish mise-en-scene. This technique has the power to transcend normal conceptions of reality, as we can see from a glance at the cinema’s first master of the technique, Georges Méliès. Méliès’s mise-en-scene enabled him to create a totally imaginary world on film.

A caricaturist and magician, Méliès became fascinated by the Lumière brothers’ demonstration of their short films in 1895. (For more on the Lumières, see

p. 186

.) After building a camera based on an English projector, Méliès began filming unstaged street scenes and moments of passing daily life. One day, the story goes, he was filming at the Place de l’Opéra, and his camera jammed as a bus was passing. After some tinkering, he was able to resume filming, but by this time, the bus had gone and a hearse was passing in front of his lens. When Méliès screened the film, he discovered something unexpected: a moving bus seemed to transform instantly into a hearse. Whether or not the anecdote is true, it at least illustrates Méliès’s recognition of the magical powers of mise-en-scene. He would devote most of his efforts to cinematic conjuring.

“When Buñuel was preparing

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie,

he chose a tree-lined avenue for the recurring shot of his characters traipsing endlessly down it. The avenue was strangely stranded in open country and it perfectly suggested the idea of these people coming from nowhere and going nowhere. Buñuel’s assistant said, ‘You can’t use that road. It’s been used in at least ten other movies.’ ‘Ten other movies?’ said Buñuel, impressed. ‘Then it must be good.’”

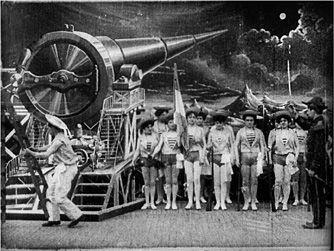

To do so would require preparation, since Méliès could not count on lucky accidents like the bus–hearse transformation. He would have to plan and stage action for the camera. Drawing on his experience in theater, Méliès built one of the first film studios—a small, crammed affair bristling with theatrical machinery, balconies, trapdoors, and sliding backdrops. He sketched shots beforehand and designed sets and costumes. The correspondence between his detailed drawings and the finished shots is illustrated in

4.3

and

4.4

. As if this were not enough, Méliès starred in his own films (often in several roles per film). His desire to create magical effects led Méliès to control every aspect of his films’ mise-en-scene.

4.3 Georges Méliès’s design for the rocket-launching scene in

A Trip to the Moon

and …

4.4 … the scene in the film.