B0041VYHGW EBOK (44 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

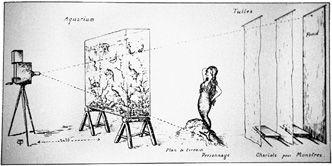

Such control was necessary to create the fantasy world he envisioned. Only in a studio could Méliès produce

The Mermaid

(

4.5

).

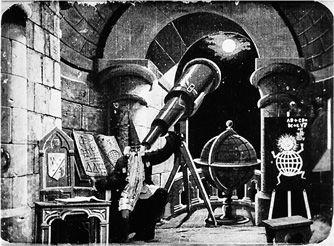

He could also surround himself (playing an astronomer) with a gigantic array of cartoonish cut-outs in

La Lune à un mètre

(

4.6

).

4.5

The Mermaid

created an undersea world by placing a fish tank between the camera and an actress, some backdrops, and “carts for monsters.”

4.6 The telescope, globe, and blackboard are all flat, painted cut-outs in

La Lune á une mètre.

Méliès’s “Star-Film” studio made hundreds of short fantasy and trick films based on such a control over every element in the frame, and the first master of mise-en-scene demonstrated the great range of technical possibilities it offers. The legacy of Méliès’s magic is a delightfully unreal world wholly obedient to the whims of the imagination.

What possibilities for selection and control does mise-en-scene offer the filmmaker? We can mark out four general areas: setting, costumes and makeup, lighting, and staging.

Since the earliest days of cinema, critics and audiences have understood that setting plays a more active role in cinema than it usually does in the theater. André Bazin writes,

The human being is all-important in the theatre. The drama on the screen can exist without actors. A banging door, a leaf in the wind, waves beating on the shore can heighten the dramatic effect. Some film masterpieces use man only as an accessory, like an extra, or in counterpoint to nature, which is the true leading character.

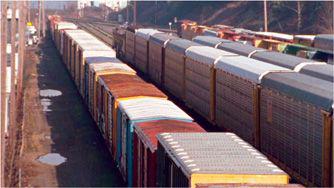

Cinema setting can come to the forefront; it need not be only a container for human events but can dynamically enter the narrative action. Kelly Reichardt’s

Wendy and Lucy

begins with shots of a railroad yard as trains pass through

(

4.7

).

But we don’t see any people. Wendy, who is making her way across the United States by car, is later seen walking her dog Lucy in a park. The opening shots of the rail yard suggest the sort of neighborhoods where she must stay. At later points in the film, the roar and whistle of rail traffic will increase suspense, but not until the ending will we come to understand why the opening emphasized the trains.

4.7 The railway yard at the opening of

Wendy and Lucy

is a setting that will take on significance later in the film.

The filmmaker may control setting in many ways. One way is to select an already existing locale in which to stage the action, a practice stretching back to the earliest films. Louis Lumière shot his short comedy

L’Arroseur arrosé

(“The Waterer Watered,”

4.8

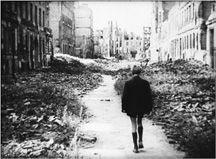

) in a garden. At the close of World War II, Roberto Rossellini shot

Germany Year Zero

in the rubble of Berlin

(

4.9

).

Today filmmakers often go on location to shoot.

4.8

L’Arroseur arrosé.

4.9

Germany Year Zero.

Alternatively, the filmmaker may construct the setting. Méliès understood that shooting in a studio increased his control, and many filmmakers followed his lead. In France, Germany, and especially the United States, the possibility of creating a wholly artificial world on film led to several approaches to setting.

Some directors have emphasized authenticity. For example, Erich von Stroheim prided himself on meticulous research into details of locale for

Greed

(

4.10

).

All the President’s Men

(1976) took a similar tack, seeking to duplicate the

Washington Post

office on a soundstage

(

4.11

).

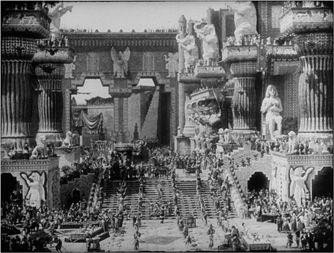

Even wastepaper from the actual office was scattered around the set. Other films have been less committed to historical accuracy. Though D. W. Griffith studied the various historical periods presented in

Intolerance,

his Babylon constitutes a personal image of that city

(

4.12

).

Similarly, in

Ivan the Terrible,

Sergei Eisenstein freely stylized the decor of the czar’s palace to harmonize with the lighting, costume, and figure movement, so that characters crawl through doorways that resemble mouseholes and stand frozen before allegorical murals

(

4.13

).

4.10 Details like hanging flypaper and posters create a tavern scene in

Greed.

4.11 Replicating an actual newsroom in

All the President’s Men.

4.12 The Babylonian sequences of

Intolerance

combined influences from Assyrian history, 19th-century biblical illustration, and modern dance.

4.13 In

Ivan the Terrible,

Part 2

, the decor makes the characters seem to wriggle from one space to another.