B0041VYHGW EBOK (42 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

Against the five character narrators, the film’s plot sets another purveyor of knowledge, the “News on the March” short. We’ve already seen the crucial function of the newsreel in introducing us both to

Kane

’s story and to its plot construction, with the newsreel’s sections previewing the parts of the film as a whole. The newsreel also gives us a broad sketch of Kane’s life and death that will be filled in by the more restricted behind-the-scenes accounts offered by the narrators. The newsreel is also highly objective, even more so than the rest of the film; it reveals nothing about Kane’s inner life. Rawlston acknowledges this: “It isn’t enough to tell us what a man did, you’ve got to tell us who he was.” In effect, Thompson’s aim is to add depth to the newsreel’s superficial version of Kane’s life.

Yet we still aren’t through with the narrational manipulations in this complex and daring film. For one thing, all the localized sources of knowledge—“News on the March” and the five narrators—are linked together by the shadowy reporter Thompson. To some extent, he is our surrogate in the film, gathering and assembling the puzzle pieces.

Note, too, that Thompson is barely characterized; we can’t even identify his face. This, as usual, has a function. If we saw him clearly, if the plot gave him more traits or a background or a past, he would become the protagonist. But

Citizen Kane

is less about Thompson than about his

search.

The plot’s handling of Thompson makes him a neutral conduit for the story information that he gathers (though his conclusion at the end—“I don’t think any word can explain a man’s life”—suggests that he has been changed by his investigation).

Thompson is not, however, a perfect surrogate for us because the film’s narration inserts the newsreel, the narrators, and Thompson within a still broader range of knowledge. The flashback portions are predominantly restricted, but there are other passages that reveal an overall narrational omniscience.

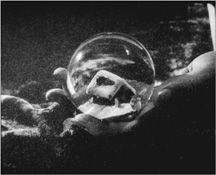

From the very start, we are given a god’s-eye-view of the action. We move into a mysterious setting that we will later learn is Kane’s estate, Xanadu. We might have learned about this locale through a character’s journey, the way we acquaint ourselves with Oz by means of Dorothy’s adventures there. Here, however, an omniscient narration conducts the tour. Eventually, we enter a darkened bedroom. A hand holds a paperweight, and over this is superimposed a flurry of snow

(

3.39

).

3.39 The elusive image of the paperweight in

Citizen Kane.

The snow image teases us. Is the narration making a lyrical comment, or is the image subjective, a glimpse into the dying man’s mind or vision? In either case, the narration reveals its ability to command a great deal of story information. Our sense of omniscience is enhanced when, after the man dies, a nurse strides into the room. Apparently, no character knows what we know.

At other points in the film, the omniscient narration calls attention to itself, as when, during Susan’s opera debut in Leland’s flashback (6i), we see stagehands high above reacting to her performance. (Such omniscient asides tend to be associated with camera movements, as we shall see in

Chapter 8

.) Most vivid, however, is the omniscient narration at the end of the film. Thompson and the other reporters leave, never having learned the meaning of Rosebud. But we linger in the vast storeroom of Xanadu. And, thanks to the narration, we learn that Rosebud is the name of Kane’s childhood sled (see

8.22

). We can now associate the opening’s emphasis on the snowy cottage with the closing scene’s revelation of the sled.

This narration is truly omniscient. It withheld a key piece of story information at the outset, teased us with hints (the snow, the tiny cottage in the paperweight), and finally revealed at least part of the answer to the question posed at the outset. A return to the “No Trespassing” sign reminds us of our point of entry into the film. Like

The Road Warrior,

then, the film derives its unity not only from principles of causality and time but also from a patterned narration that arouses curiosity and suspense and yields a surprise at the very end.

Not every narrative analysis runs through the categories of cause–effect, story–plot differences, motivations, parallelism, progression from opening to closing, and narrational range and depth in that exact order, as we have done here. Our purpose in this examination of

Citizen Kane

has been as much to illustrate these concepts as to analyze the film. With practice, the critic becomes more familiar with these analytical tools and can use them flexibly, suiting his or her approach to the specific film at hand.

In looking at any narrative film, such questions as these may help in understanding its formal structures:

- Which story events are directly presented to us in the plot, and which must we assume or infer? Is there any nondiegetic material given in the plot?

- What is the earliest story event of which we learn? How does it relate to later events through a series of causes and effects?

- What is the temporal relationship of story events? Has temporal order, frequency, or duration been manipulated in the plot to affect our understanding of events?

- Does the closing reflect a clear-cut pattern of development that relates it to the opening? Do all narrative lines achieve closure, or are some left open?

- How does the narration present story information to us? Is it restricted to one or a few characters’ knowledge, or does it range freely among the characters in different spaces? Does it give us considerable depth of story information by exploring the characters’ mental states?

- How closely does the film follow the conventions of the classical Hollywood cinema? If it departs significantly from those conventions, what formal principle does it use instead?

Most films that we see employ narrative form, and the great majority of theatrical movies stick to the premises of Hollywood storytelling. Still, there are other formal possibilities. We’ll consider aspects of non-narrative form in

Chapter 11

.

In the meantime, other matters will occupy us. In discussing form, we’ve been examining how we as viewers engage with the film’s overall shape. The film, however, also presents a complex blend of images and sounds. Art designers, actors, camera operators, editors, sound recordists, and other specialists contribute to the cues that guide our understanding and stimulate our pleasure. In

Part Three

, we’ll examine the technical components of cinematic art.

WHERE TO GO FROM HERE

The best introduction to the study of narrative is H. Porter Abbott’s

Cambridge Introduction to Narrative,

2d ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008). A more advanced collection of essays is David Herman, ed.,

The Cambridge Companion to Narrative

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007). For an overview of narrative in history and culture, see Robert Scholes and Robert Kellogg,

The Nature of Narrative

(New York: Oxford University Press, 1966).

Most conceptions of narrative are drawn from literary theory. Umberto Eco’s

Six Walks in the Fictional Woods

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994) provides an entertaining tour. A more systematic introduction is offered by Seymour Chatman in

Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film

(Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1978). See also the journal

Narrative

and the anthology edited by Marie-Laure Ryan,

Narrative Across Media: The Languages of Storytelling

(Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004). David Bordwell offers a survey of narrative principles in “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative,”

Poetics of Cinema

(New York: Routledge, 2007),

pp. 85

–133. Other essays in this book analyze forkingpath films like

Run Lola Run

and “network narratives” like

Nashville

and

Magnolia.

What does the spectator

do

in making sense of a narrative? Richard J. Gerrig proposes what he calls a “sideparticipant” model in

Experiencing Narrative Worlds: On the Psychological Activities of Reading

(New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993). Meir Sternberg emphasizes expectation, hypotheses, and inference in his

Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction

(Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978). David Bordwell proposes a model of the spectator’s story-comprehending activities in

chap. 3

of

Narration in the Fiction Film

(Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985). Compare Edward Branigan,

Narrative Comprehension in Film

(New York: Routledge, 1992).

Most theorists agree that both cause–effect relations and chronology are central to narrative. The books by Chatman and Sternberg cited above provide useful analyses of causation and time. For specifically cinematic discussions, see Brian Henderson, “Tense, Mood, and Voice in Film (Notes After Genette),”

Film Quarterly

26, 4 (Summer 1983): 4–17; and Maureen Turim,

Flashbacks in Film: Memory and History

(New York: Routledge, 1989).

Our discussion of the differences between plot duration, story duration, and screen duration is necessarily simplified. The distinctions hold good at a theoretical level, but the differences may vanish in particular cases. Story duration and plot duration differ most drastically at the level of the

whole

film, as when two years of action (story duration) are shown or told about in scenes that occur across a week (plot duration) and then that week is itself rendered in two hours (screen duration). At the level of a smaller

part

of the film—say, a shot or a scene—we usually assume story and plot duration to be equal, and screen duration may or may not be equal to them. These nuances are discussed in

chap. 5

of Bordwell,

Narration in the Fictional Film

(cited above).

One approach to narration has been to draw analogies between film and literature. Novels have first-person narration (“Call me Ishmael”) and third-person narration (“Maigret puffed his pipe as he walked along slowly, hands clasped behind his back”). Does film have first-person or thirdperson narration, too? The argument for applying the linguistic category of “person” to cinema is discussed most fully in Bruce F. Kawin,

Mindscreen: Bergman, Godard, and First-Person Film

(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978).

Another literary analogy is that of point of view. The best survey in English is Susan Snaider Lanser,

The Narrative Act: Point of View in Prose Fiction

(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981). The applicability of point of view to film is discussed in detail in Edward Branigan,

Point of View in the Cinema: A Theory of Narration and Subjectivity in Classical Film

(New York: Mouton, 1984).

The title of a film can be an important factor in its narration, setting us up for what is to come. We reflect on what kinds of titles Hollywood tends to use here in “Title wave,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=2805

.

On credit sequences, see Gemma Solana and Antonio Boneu,

Uncredited: Graphic Design and Opening Titles in Movies

(Amsterdam: Index Books, 2007).

Since the early 1990s, some film historians have claimed that the classical approach to Hollywood narrative faded away during the 1970s, replaced by something variously termed

postclassical, postmodern,

or

post-Hollywood cinema.

Contemporary films are thought to be characterized by extremely simple, high-concept premises, with the cause–effect chain weakened by a concentration on highpitch action at the expense of character psychology. Tie-in merchandising and distribution through other media have also supposedly fragmented the filmic narrative. Other historians argue that the changes are superficial and that in many ways underlying classical principles endure.

For important arguments for postclassicism, see Thomas Schatz, “The New Hollywood,” in

Film Theory Goes to the Movies,

ed. Jim Collins, Hilary Radner, and Ava Preacher Collins (New York: Routledge, 1993),

pp. 8

–36, and Justin Wyatt,

High Concept: Movies and Marketing in Hollywood

(Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994).

Contemporary Hollywood Cinema,

ed. Steven Neale and Murray Smith (New York: Routledge, 1998), contains essays supporting (by Thomas Elsaesser, James Schamus, and Richard Maltby) and opposing (Murray Smith, Warren Buckland, and Peter Krämer) this notion. For arguments that Hollywood cinema still adheres to its traditions, see Kristin Thompson,

Storytelling in the New Hollywood: Understanding Classical Narrative Technique

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), and David Bordwell,

The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006).

Screenwriting teachers have also argued that the best modern moviemaking continues the classic studios’ approach to structure. The two most influential script gurus are Syd Field,

Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting

(New York: Delta, 2005), and Robert McKee,

Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting

(New York: HarperCollins, 1997).

Critics have scrutinized

Citizen Kane

very closely. For a sampling, see Joseph McBride,

Orson Welles

(New York: Viking, 1972); Charles Higham,

The Films of Orson Welles

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970); Robert Carringer, “Rosebud, Dead or Alive: Narrative and Symbolic Structure in

Citizen Kane,

”

PMLA

(March 1976): 185–93; James Naremore,

The Magic World of Orson Welles

(New York: Oxford University Press, 1978); Laura Mulvey,

Citizen Kane

(London: British Film Institute, 1993); and James Naremore, ed.,

Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane: A Casebook

(New York: Oxford University Press, 2004).

Pauline Kael, in a famous essay on the making of the film, finds Rosebud a naïve gimmick. Interestingly, her discussion emphasizes

Citizen Kane

as part of the journalist film genre and emphasizes the detective story aspect. See

The “Citizen Kane” Book

(Boston: Little, Brown, 1971),

pp. 1

–

pp. 155

–65, Noël Carroll argues that the film stages a debate between the Rosebud interpretation and the enigma interpretation. Robert Carringer’s

Making of “Citizen Kane,”

rev. ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), offers the most extensive account of the film’s production.

www.screenwritersutopia.com/

Contains discussion of screenwriting problems, including debates about classic screenplay structure.

www.wga.org/writtenby/writtenby.aspx/

The official site of the magazine

Written By,

published by Writers Guild West, the professional organization of American screenwriters. Includes informative articles about trends in screenwriting.

Recommended DVD Supplementswww.creativescreenwriting.com/index.html/

Another magazine,

Creative Screenwriting,

that publishes selected articles and interviews online.

Discussions of narrative form are rare in DVD supplements. In “Making of

Titus,

” director Julie Taymor talks about such narrative elements as motifs, point of view, tone, and emotional impact, as well as the functions of film techniques such as music, setting, editing, cinematography, and lighting. In an unusual supplement for

The Godfather,

“Francis Coppola’s Notebook,” the director shows how he worked by making detailed annotations in his copy of Mario Puzo’s original novel. Coppola discusses rhythm, emphasis, and the narrative functions of various techniques. The “Star Beast: Developing the Story” section of

Alien

’s supplements traces the story as it went through a series of very different versions.

“Filmmakers’ Journey

Part One

,” a supplement for

The Da Vinci Code,

discusses character, timing, and rhythm. One passage that is particularly good for showing how filmmakers think about the form of films comes in a segment on the introduction of a major new character (Sir Lee Teabing) fully halfway through the film. There is also discussion of the film’s series of journeys: “There was this sort of classic structure that we were working with.”

The Warner Bros. DVD of

Citizen Kane

offers a remastered print of the film with commentary tracks by Roger Ebert and Peter Bogdanovich. A second disc contains a two-hour documentary,

The Battle over Citizen Kane,

exploring William Randolph Hearst’s efforts to have RKO destroy the film.