B0041VYHGW EBOK (78 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

5.106

La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc.

Categories of framing are obviously matters of degree. There is no universal measure of camera angle or distance. No precise cutoff point distinguishes between a long shot and an extreme long shot, or a slightly low angle and a straight-on angle. Moreover, filmmakers are not bound by terminology. They don’t worry if a shot does not fit into traditional categories. (Nevertheless, abbreviations like MS for medium shot and CU for close-up are regularly used in screenplays, so filmmakers do find these terms useful in their work.) In most cases, the concepts are clear enough for us to use them in talking about films.

“I don’t

like

close-ups unless you can get a kick out of them, unless you

need

them. If you can get away with attitudes and positions that show the feeling of the scene, I think you’re better off using the close-up only for absolute punctuation—that’s the reason you do it. And you save it—not like TV where they do

everything

in close-up.”— Howard Hawks, director,

His Girl Friday

Sometimes we’re tempted to assign absolute meanings to angles, distances, and other qualities of framing. It is easy to claim that framing from a low angle automatically presents a character as powerful and that framing from a high angle presents him or her as dwarfed and defeated. Verbal analogies are especially seductive: a canted frame seems to mean that “the world is out of kilter.”

The analysis of film as art would be a lot easier if technical qualities automatically possessed such hard-and-fast meanings, but individual films would thereby lose much of their uniqueness and richness. The fact is that framings have no absolute or general meanings. In

some

films, angles and distance carry such meanings as mentioned above, but in other films—probably most films—they do not. To rely on formulas is to forget that meaning and effect always stem from the film, from its operation as a system. The context of the film determines the function of the framings, just as it determines the function of mise-en-scene, photographic qualities, and other techniques. Consider three examples.

At many points in

Citizen Kane,

low-angle shots of Kane do convey his looming power, but the lowest angles occur at the point of Kane’s most humiliating defeat—his miscarried gubernatorial campaign

(

5.107

).

Note that angles of framing affect not only our view of the main figures but also the background against which those figures may appear.

5.107 In

Citizen Kane,

the low angle functions to isolate Kane and his friend against an empty background, his deserted campaign headquarters.

If the cliché about high-angle framings were correct,

5.108

, a shot from

North by Northwest,

would express the powerlessness of Van Damm and Leonard. In fact, Van Damm has just decided to eliminate his mistress by pushing her out of a plane, and he says, “I think that this is a matter best disposed of from a great height.” The angle and distance of Hitchcock’s shot wittily prophesy how the murder is to be carried out.

5.108

North by Northwest.

Similarly, the world is hardly out of kilter in the shot from Eisenstein’s

October

shown in

5.109

. The canted frame dynamizes the effort of pushing the cannon.

5.109 A dramatic canted framing from

October.

These three examples should demonstrate that we cannot reduce the richness of cinema to a few recipes. We must, as usual, look for the

functions

the technique performs in the particular

context

of the total film.

Camera distance, height, level, and angle often take on clear-cut narrative functions. Camera distance can establish or reestablish settings and character positions, as we shall see in the next chapter when we examine the editing of the first sequence of

The Maltese Falcon.

A framing can isolate a narratively important detail

(

5.110

,

5.111

).

5.110 The tears of Henriette in

A Day in the Country

are visible in extreme close-up.

5.111 In

Day for Night,

a close framing emphasizes the precision with which the film director positions an actor’s hands.

Framing also can cue us to take a shot as subjective. In

Chapter 3

, we saw that a film’s narration may present story information with some degree of psychological depth (

p. 95

), and one option is a perceptual subjectivity that renders what a character sees or hears. When a shot’s framing prompts us to take it as seen through a character’s eyes, we call it an optically subjective shot, or a point-of-view (POV shot). (See also

p. 200

.) Fritz Lang’s

Fury

provides a clear example

(

5.112

,

5.113

).

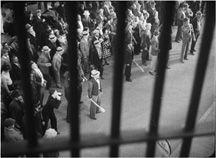

5.112 In

Fury,

the hero in his jail cell is seen through the bars from a slightly low angle …

5.113 … while the next shot, a high angle through the window toward the street outside, shows us what he sees, from his point of view.

Framings may serve the narrative in yet other ways. Across an entire film, the repetitions of certain framings may associate themselves with a character or situation. That is, framings may become motifs unifying the film

(

5.114

).

Throughout

La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc,

Dreyer returns obsessively to extreme close-up shots of Jeanne (

4.130

).