Becoming American: Why Immigration Is Good for Our Nation's Future (12 page)

Read Becoming American: Why Immigration Is Good for Our Nation's Future Online

Authors: Fariborz Ghadar

With the help of his wife, Pam, Omidyar created the Omidyar Network in 2004. Broadening the scope of the Omidyar Foundation, which had only financed nonprofit endeavors, the Network also provides money for profit ventures that advance its goals.

10

Omidyar said one of the results of eBay has been in its ability to show the trust strangers can share when exchanging money and goods online. Despite never having met in person or having mutual friends, these people still make these transactions, with the only physical proof being a photograph. Equal funds are set aside for nonprofit and profit concerns.

In addition to having served as a Tufts trustee, Omidyar was selected by President Barack Obama to serve as a commissioner on the President’s Commission on White House Fellowships in 2009.

11

In 2010, Omidyar founded

Honolulu Civil Beat

, a local online news service devoted to civic engagement and public affairs journalism.

12

However, most countries often consider two persistent questions about lower-skilled immigrants: given concerns about competition with native workers, how many immigrants should be permitted, under which circumstances, and into which occupations? And should these flows be temporary, permanent, or circular?

Chegg

Aayush Phumbhra, a native of India, is cofounder of Chegg, Inc. and serves as senior vice president. Prior to moving to the United States in 2001, Aayush founded two additional companies, one of which popularized peanut butter and chocolate spreads in his native country.

Phumbhra’s next business venture,

Chegg.com

, was his big break. Phumbhra conceived of the idea of Chegg through his personal experience and frustration with his own university’s bookstore. Thus, the mission of Chegg is “to enable college students to save a significant amount of money by letting them rent textbooks rather than buy them.”

13

The name of the company itself is a bit humorous. While studying in Iowa in 2001, Aayush Phumbhra contemplated “the chicken and egg dilemma” for students searching for a job. Employers look for work experience, but students need to have a job to have work experience. By mashing the words

chicken

and

egg

together, Phumbhra came up with Chegg.

14

Because of how it operates, Chegg is often referred to as “Netflix for textbooks.” It allows students at more than six thousand colleges to rent from an online bookstore equipped with 4.2 million books.

Yet Chegg’s success story varies from the common tale of other breakout startups, such as Groupon and Zynga. Instead of founding a completely new industry, Chegg introduced an established service idea and relied on traditional customer behavior (mail-order rentals) in an archaic, defective category, whose customers felt confined by high costs. Although Chegg did not initially find success in 2003, it established a steady business flow within four years.

15

The United States is no exception to this concern. Its employment-based visa regime is divided into two separate systems: temporary (known as nonimmigrant) and permanent (known as immigrant). Most long-term employment-based immigrants must apply through both systems, one to enter the country and again to gain permanent residence. In the vast majority of cases, both applications require an employer sponsor. Receiving a green card for permanent residence takes considerable time, in part because of the strict, permanent, numerical limits on visas. Virtually all (about 90 percent) of employment-based green-card recipients, therefore, arrive on temporary visas and later adjust to permanent residence from within the country.

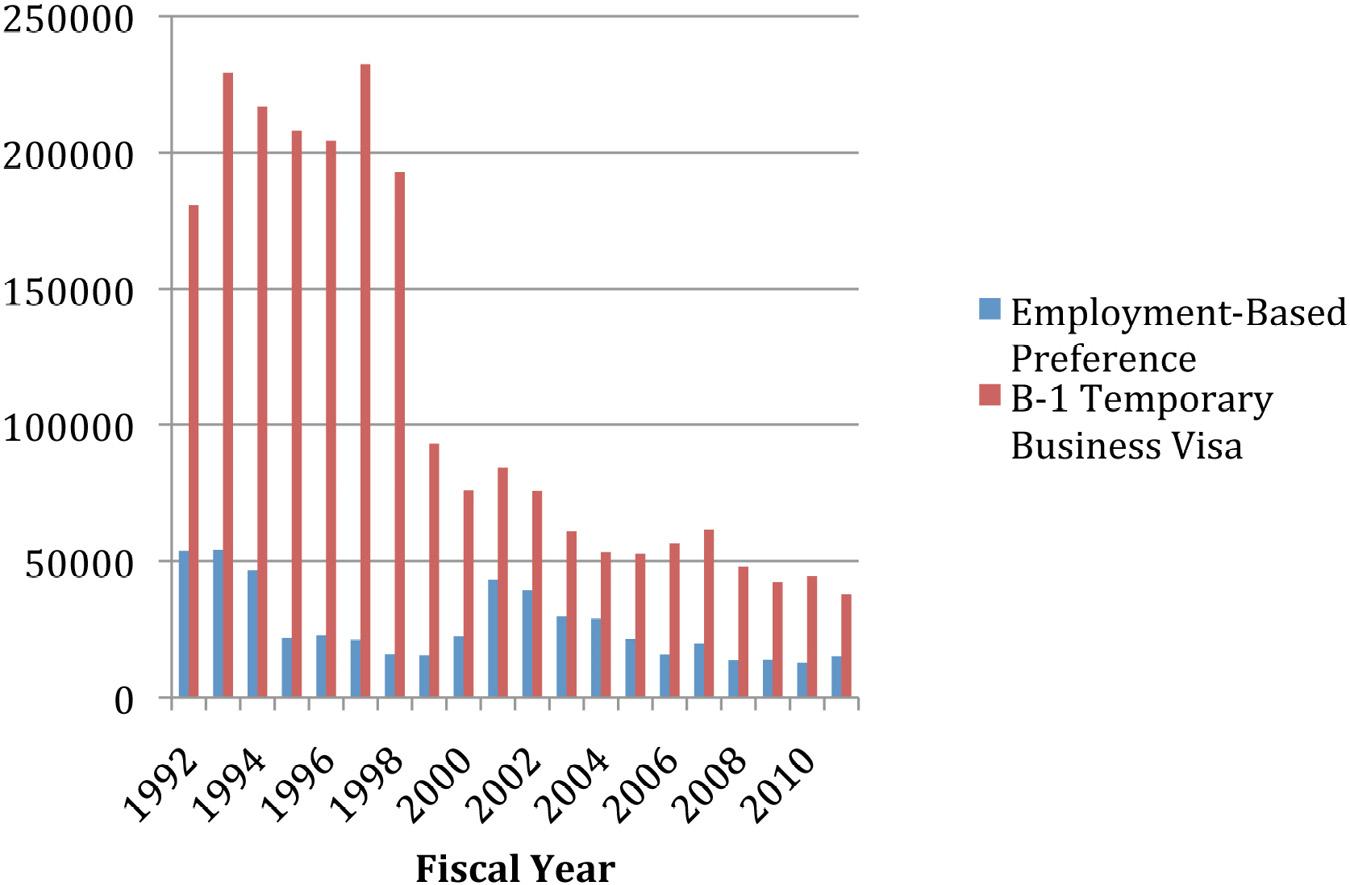

The chart below shows the level of employment-based visas over the past two decades (1992–2010) issued to permanent immigrants (employment-based preference) and temporary nonimmigrants (B-1 temporary visitor for business purposes).

Employment-Based Visas (1992–2010)

U.S. Department of State,

Classes of Nonimmigrants Issued Visas (Including Crewlist Visas and Border Crossing Cards) Fiscal Years 1992–2010

,

http://www.travel.state.gov/pdf/MultiYearTableI.pdf

.

Immigrant and Nonimmigrant Visas Issued at Foreign Service Posts Fiscal Years 1992–2011

,

http://www.travel.state.gov/pdf/MultiYearTableXVI.pdf

.

Only about 15 percent of visas for legal permanent residence (“green cards”) are issued to economic-stream immigrants in the United States. About half of the visas go to the family members of employer-sponsored immigrant workers (the “principal” applicants). The share of employment-based immigrants in the United States is low compared to other immigrant-receiving nations in the English-speaking world (even if the United States remains the largest recipient of skilled migrants). In Australia, for example, economic-stream immigration accounts for about two-thirds of the total, and in the United Kingdom, it accounts for just over two-fifths, excluding the substantial flows of primarily labor-motivated immigration from within the European Union.

The United States operates two strictly temporary, employment-based migration schemes for mostly perishable-crop agricultural and seasonal or temporary nonagricultural jobs. Agricultural visas, also known as H-2A visas, are uncapped but subject to a complex web of requirements that leave neither employers nor workers and their advocates satisfied; in recent years approximately sixty thousand have been issued per year. The number of nonagricultural visas, also known as H-2B visas, is capped at thirty-three thousand per six-month period. Even though the labor demand during the economic crisis was incredibly low, the thirty-three-thousand cap was typically exhausted after an average of 100 to 150 days. Note that, while these visas are not used exclusively for low-wage workers (H-2B recipients include small numbers of more highly skilled workers, including architects, engineers, managers, and creative artists, for example) and not all low-wage workers have low levels of formal education, the majority of immigration through this category is into low-paying, less-skilled occupations.

H-1B visas, on the other hand, are administered to immigrants who have a higher education degree. Only five days after the application-filing period opened for H-1B visas for the fiscal year 2014, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services had reached the statutory cap of eighty-five thousand. The H-1B cap is comprised of the regular cap, for which sixty-five thousand visas are available, and the ADE cap, for which twenty thousand visas are available. Most people are familiar with the sixty-five-thousand regular cap, which is for those who are living abroad and are obtaining their first H-1B visa and for those who are in the United States and want to change their visa status to H-1B. The ADE cap, or Advanced Degree Exemption cap, is given to foreign students who graduate from a U.S. university with a graduate degree. H-1B visas are typically valid for between three to six years. They are typically applied for by companies, rather than by individuals, and most often by companies seeking engineers, computer programmers, and other high-tech workers.

16

The H-1B visas submitted in 2012 for fiscal year 2013 ran out in just ten weeks. In 2012, the unemployment rate for computer and math occupations was 3.5 percent, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which indicates a lack of U.S. workers with these skills. This visa limitation thus stifles economic growth for months and months until the next H-1B visa-application-filing period begins. As Karen Jones, vice president and general counsel at Microsoft indicates,

Companies like Microsoft—who employ significant numbers of American workers and generate high-paying jobs in the U.S. both directly and indirectly—must be able to hire top talent in areas where we have a shortage of workers in order to succeed and grow in a highly competitive global market. This barrier to hiring puts our country at a competitive disadvantage. While U.S. employers are precluded from hiring high skilled workers from around the world, other countries—like Australia, Canada, Chile, Germany and Singapore—are actively attracting these same types of workers and thereby strengthening their competitive capabilities in the global market. Some countries are also actively engaged in programs to repatriate top talent from the U.S. For example, China has offered significant economic incentives to encourage the repatriation of Chinese nationals who have established themselves in the U.S. as scientific elites, high-level managers and entrepreneurs.

As a result of the visa restrictions, smaller tech companies have begun to set up operations abroad to gain access to highly skilled labor. In the past, foreign workers were hired to cut costs, but today foreign workers are hired because companies want the cream of the crop, regardless of geographic location. According to the article “Tech Firms Go Abroad to Hire,” written by John Shinal for

USA Today

, “A growing number of small, private U.S. technology companies—who . . . are late-stage start-ups with more than $100 million in annual sales—now have engineering offices overseas.”

17

Rather than restricting access to top global talent, our country’s approach to highly skilled immigration should be enabling U.S. companies to attract and to retain the world’s brightest minds so that our economy and our workforce can reap the economic benefits of their brainpower and contributions over the long term.

Wernher Von Braun, a German rocket scientist who worked for the Nazis during World War II, developed the V-1 and V-2 rockets that terrorized London. He, along with many of his fellow engineers and scientists, was recruited by the Americans after the war to help in the development of missiles and rocketry. He became a naturalized citizen in 1955 and led the team of mostly German-immigrant scientists in the development of the Saturn rockets, which were used to send men to the moon.

A recent study by the Kauffman Foundation highlighted entrepreneurs as the job incubators, with data that indicates an entrepreneur has the potential to create, on average, 512 jobs in his or her lifetime. Research has also found that for every one hundred foreign students who receive an advanced STEM degree and stay in the United States, 262 additional jobs are created. Thus, the low visa numbers do not make economical sense for three reasons: first, we lose the foreign students we spent vast resources training; second, we lose all of the secondary jobs that would have been created had we kept the students; and third, other countries reap the benefits of our education system, and secondary jobs are made abroad instead of in America. In addition, we limit our own access to the top talent of other countries and thereby limit our access to hardworking, entrepreneurial immigrants who have historically contributed to America’s wealth and knowledge.

Regardless of education level, method of entry into the United States, or country of origin, immigrants seem to have two traits in common: perseverance and hard work. Since they are the ones who have had the courage, desperation, or necessity to leave home and to pursue an uncertain future in a frequently foreign culture, for them, failure is not an option. They are determined to make a new life for themselves, and their hard work pays off. The single most important factor in successful companies is the people, and this is why we see immigrants make such a huge success of their efforts once they reach our shores.

We need not look much further than Zbigniew Brzezinski, Emilie Benes, and their family; Sergey Brin; Omid Kordestani; Pierre Omidyar; Aayush Phumbhra; and Nguyen and Phong Phan, and their son Loc to see how in each of these different stories of immigration, each immigrant was determined to see his or her hard work pay off, and it did.

I have met many hardworking immigrants in my lifetime from different industries and places. One man that has left an impression on me is Salomon Garay, my family’s house painter, because he produces the highest quality work and then goes above and beyond.