Becoming American: Why Immigration Is Good for Our Nation's Future (31 page)

Read Becoming American: Why Immigration Is Good for Our Nation's Future Online

Authors: Fariborz Ghadar

As an immigrant from Mexico who worked the farm fields and ranches across the western United States for nearly thirty years before retiring back in his homeland, Jesus Silva and his offspring typified the American immigrant experience.

Silva came to the United States in 1952, invited by the government under the labor-seeking Bracero Program. It began during World War II and continued in the postwar era, when America needed the help of immigrant laborers during an era of tremendous economic and population growth.

He had earned enough to spend his senior years in relative prosperity in Pajacuaran, Mexico. He owned his home, modest though it was compared to the homes he would see in the United States. But his Mexican-born children chose to remain in America, where they raised families and where their families went from being laborers in the fields with little education to employees of companies determined to see their children enter college in order to enter a professional field, such as law or medicine.

I have seen this phenomenon at work in different levels within my own family. While my parents mainly associated with fellow Iranians and relatives, my sister and I made friends with and each married outside our nationality. I married an American, and my sister married an Egyptian. My three children are even one more step removed from the life and roots of their Iranian heritage. My oldest daughter, Otessa, a successful independent filmmaker (who went back to being called Otessa when she went to college), is engaged to an Uruguayan American. While my parents thought that my career endeavors in the computer industry were crazy and doomed to failure, my initial reaction when Otessa changed from being a science major at Columbia University to filmmaking was incredulity and skepticism. However, it has been her hard work and determination that has made her successful in her career, just as it was in my sister’s and mine.

Regardless, it is difficult to imagine that I could have achieved as much as I have today without the impact of various mentors along the way and the U.S. mind-set of itself being the land of opportunity. Besides the importance of education and hard work my parents instilled, I can identify key individuals whose influence and advice were crucial to my success. The first was Dr. Richter at Ursinus College, without whom I would never have been encouraged to set my sights on MIT and Harvard. Dr. Stobaugh of Harvard nurtured my academic interests, and Minister of Commerce Kazem Khosroushahi in Iran took me under his wing when I needed guidance. Then there was Abdullah Jumah at Saudi Aramco, who recognized my drive to help educate the next generation of leaders, and he has continued to consult with me on their yearly senior management identification process since 1979. And lastly, William A. Schreyer, Chairman Emeritus of Merrill Lynch, took a chance on a driven immigrant and granted me the first endowed chair with his name.

Because I was able to recognize how critical this mentorship was to my success, I, too, have taken it upon myself and consider it my duty to mentor youth I have met throughout my life. Through acting as a consultant and through teaching at various universities, I have encountered thousands of students, managers, and executives whom I hope to have inspired. In particular, I remember Babak, who went on to work for Exxon; Hamed, an IT guru for the financial sector; Nimrata, who is a manager at Dell’s supply-chain operations; Krishna, who joined Westfield in the actuarial area; Holly, who is developing apps in Canada; and Baljit, who is a famous economic development expert. And the same can be said for many immigrants who chose education and thus were mentors to many—such as Yoon-shik Park, who teaches at George Washington University; Michel Amsalem, who taught at Columbia University; and Zbigniew Brzezinski, who teaches at SAIS. All of us hope that we have done our part to help the next generation excel and contribute to society in their own way.

While the winds of ignorance and intolerance still buffet America today, within the last thirty years more Americans, particularly the younger generations, have come to embrace diversity, viewing it as America’s strength, not its weakness.

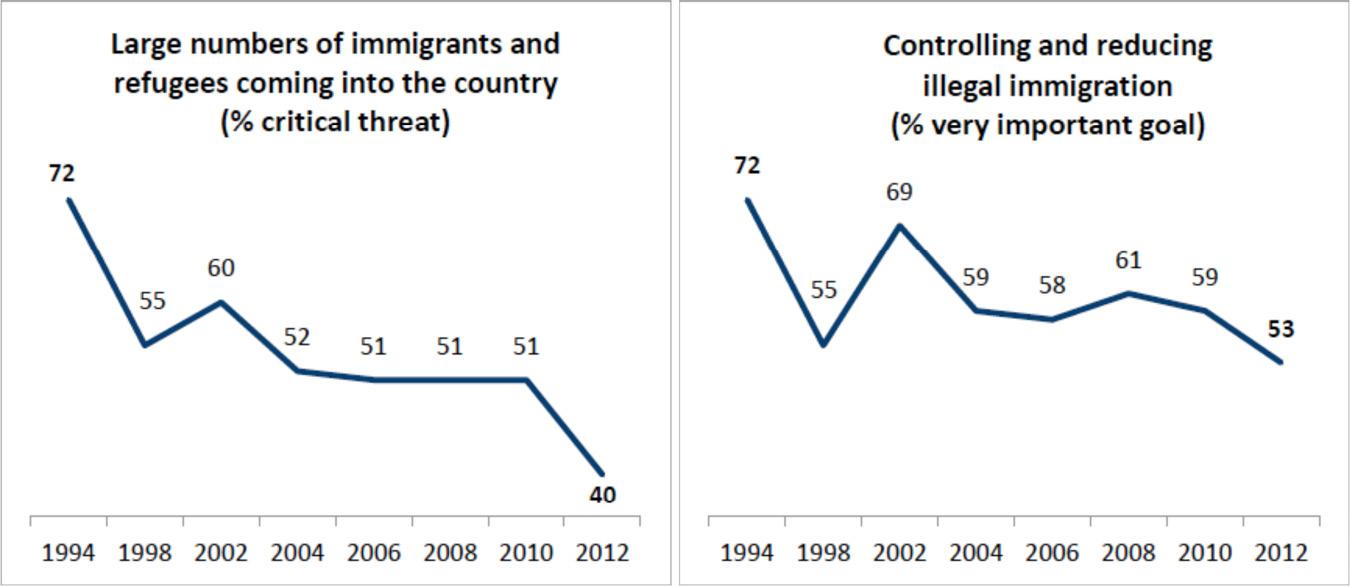

For the first time since 1994, when the Chicago Council Survey

first asked the question, only a minority (40 percent) of Americans consider a large influx of immigrants and refugees a “critical threat” to the United States. And fewer now than ever recorded in these surveys (53 percent) say that “controlling and reducing illegal immigration” is an important foreign policy goal for the United States.

Chicago Council Survey Results

Dina Smeltz, “Foreign Policy in the New Millennium,” 2012 Chicago Council Survey,

www.thechicago council.org/files/Studies_Publications/POS/Survey2012/2012.aspx

.

A new federal immigration program, known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, opened on August 15, 2012, after being put in place by the Obama administration. It protects eligible immigrants from deportation and allows them to apply for a work permit. Among other criteria, applicants must provide documentation showing they arrived in the United States before they were sixteen years old, are under the age of thirty-one, and have lived continuously in the United States for the past five years. But the program doesn’t offer legal residency or a path to citizenship, and participants must reapply for authorization every two years.

Within two months of the start of the new program, about 180,000 young illegal immigrants applied for the two-year reprieve from deportation. Thus far, 4,591 cases have been approved, according to the Department of Homeland Security.

For the first time since the question was asked in 2002, the 2012 Chicago Council Survey

found more Americans support keeping immigration at present levels (42 percent) than favor decreasing them (37 percent). This is a striking change in opinion from ten years ago when six in ten Americans favored decreasing immigration levels. While still relatively low, the proportion of Americans supporting an increase in legal immigration levels over the past ten years has more than doubled, from 7 percent in 2002 to 18 percent today.

American Opinion on Immigration Level

Dina Smeltz, “Foreign Policy in the New Millennium,” 2012 Chicago Council Survey,

www.the chicagocouncil.org/files/Studies_Publications/POS/Survey2012/2012.aspx

.

New York Times

Washington bureau chief David Leonhardt writes that today’s generation gap is wider than it has been since the 1960s, and that,

beyond political parties, the two have different views on many of the biggest questions before the country. The young not only favor gay marriage and school funding more strongly; they are also notably less religious, more positive toward immigrants, less hostile to Social Security cuts and military cuts and more optimistic about the country’s future. They are both more open to change and more confident that life in the United States will remain good.

One striking illustration of the young, and specifically the immigrant, being open to change is Iranian immigrant Babak Parviz and German immigrant Sebastian Thrun of Google X. They have recently revealed Project Glass, futuristic eyewear that is like a computer screen overlaid on the real world.

What second-generation Russian immigrant and Google cofounder Sergey Brin started, they are taking into a whole other realm. It is no accident that they are involved in the next big thing (nanotechnology and biotechnology), and in addition to this project, partner Thrun is also developing unmanned robotic cars that drive more safely. They each have that common immigrant combination: a risk-taking spirit and a strong work ethic.

Many of today’s young immigrants are finding careers in completely new industries and fields. The “app” economy barely existed five years ago, yet in that same time frame, it has spawned 470,000 new jobs. These new fields generate the need for talent with new skills.

Yet by 2018, the number of working Americans fifty-five years or older will have increased by 5.8 percent over the past decade, while only 12.7 percent of the labor force will be aged sixteen to twenty-four.

1

This means that the United States will be required to maintain an aging workforce that works well into the retirement years. According to a report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, in an aging workforce, “employees may become less adaptable and mobile, innovation and entrepreneurship may decline, rates of savings and investment may fall, public-sector deficits may rise, and current account balances may turn negative. All of this threatens to impair economic performance.”

2

In other words, we need to remember that learning and refreshing one’s skill set must become a lifelong endeavor.

The lessons I take as I look back and even as I look forward to my own children and their immigrant peers are ones of remembering to never lose the fire. The world no longer consists of protected markets and stagnant populations. The only way to succeed is to take a lesson from this immigrant book: work hard and take risks.

NOTES

1. John Hagel III, John Seely Brown, and Duleesha Kulasooriya, “The 2011 Shift Index: Measuring the Forces of Long-Term Change,”

Deloitte Center for the Edge

1 (2011): 17.

2. Richard Jackson and Neil Howe, with Rebecca Strauss and Keisuke Nakashima,

The Graying of the Great Powers: Demography and Geopolitics in the 21st Century

(Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, May 2008).

24

Blueprints for Policymakers

I

mmigration is central to the story of the United States, and figuring out how to do it right in the twenty-first century is both critically important and politically loaded to the point in which rational debate is impossible: case in point, nobody knew for sure whether candidate Herman Cain’s proposal for an electrified fence on the Mexican border was a joke.

In the pursuit of tight borders, current U.S. immigration policy turns away potential contributors to our economic strength. Open borders are not an option for any sovereign nation of significant size. At the same time, periods of intense nativism in U.S. history have spurred extremely restrictive policies. As history should show conclusively, the cost of barring potential entrepreneurs is high. Former Citibank CEO Walter Wriston once commented about money that “capital goes where it’s wanted, and stays where it’s well treated,” but in a global economy that runs on ideas, talent, and hard work, the statement holds even more true for brainpower.

U.S. students’ rapidly declining interest in STEM is even more portentous. The United States accounts for only 4 percent of the total engineering degrees awarded globally, while Asia accounts for 56 percent of the degrees granted.

Technology-based industries tend to create large numbers of high-paying jobs and to generate large volumes of high-margin exports. Worse still, even the most staid industries are being forced to become technology industries. The future of automobiles, we are told, is in new fuel-efficient, self-driving designs. Even utilities are being forced to go high tech, with the need to move to clean coal and renewable energy sources and to build and to manage smart infrastructures. Hopefully, factors such as growing interest in biotech, nanotech, robotics, sustainability, and new education incentives and programs (such as those that encourage math and science education) will increase domestic interest in STEM education and careers. If not, the United States will need to recognize the necessity of encouraging and better using the gift of foreign-born talent nurtured by our universities.