Becoming American: Why Immigration Is Good for Our Nation's Future (33 page)

Read Becoming American: Why Immigration Is Good for Our Nation's Future Online

Authors: Fariborz Ghadar

“Employers are best positioned to decide who can best fill the open jobs rather than a passive and bureaucratic system,” Kenney said, dismissing the idea that such an initiative could give the private sector too much power at the expense of the federal government. “It’s not about privatizing the immigration system, it’s about a more active role of recruitment for people so they have jobs when they show up. I’d rather have an engineer working as an engineer than as a cab driver. That’s really where we’re trying to go with this.”

In 2007, Microsoft opened a Development Center in Vancouver, Canada. The most significant reason for doing this, and the one that stimulated much debate, centered on immigration and temporary foreign workers. With a high demand for foreign information technology workers, Microsoft chairman Bill Gates has long lobbied the American government to ease restrictions on H-1B visas. Recognizing that American immigration policy is not likely to change in the near future, Microsoft realized that Canada’s more open immigration system for foreign skilled workers is a more attractive option. The Canadian software development center will allow “the company to recruit and retain highly skilled people affected by immigration issues in the U.S.”

4

Those Microsoft employees on H-1B visas, who would have to leave the United States when their visas expire, now have the option to transfer to the Microsoft development center in Canada. This works well for Microsoft. It can maintain these trained and valued employees; it can benefit from Canada’s more open temporary foreign worker program to recruit additional IT workers from abroad; and its foreign employees can more easily become permanent residents and Canadian citizens. Employees are therefore more long term. The new Microsoft Canada Development Centre also works well for Canada. The country will benefit from the influx of foreign IT workers and the increased investment in Canada’s software development industry.

It should cause U.S. policymakers some concern that the heading on Microsoft’s Vancouver Development Center’s web page says it is the “Destination for the World’s Best.”

Immigration Minister Kenney went so far as to go to Ireland this year for an official visit to promote Canada as a destination for international talent. “The Government of Canada is committed to building an immigration system that actively recruits talent rather than passively processing all applications that we receive,” said Kenney. He visited Dublin’s Working Abroad Expo recruitment fair, where he promoted Canada’s strong economy and encouraged talent from Ireland to apply for jobs to work in Canada.

The Construction Sector Council of Canada forecasts that it will need an estimated 319,000 new construction workers between 2012 and 2020, as resource projects peak and retirements continue to rise across the country. The forecast estimates a need for one hundred thousand jobs due to expansion demands in the mining, oil and gas, electricity, and transportation sectors.

The government of Canada is building a fast and flexible economic immigration system with a primary focus on meeting Canada’s labor market needs. The government is exploring provinces, territories, and employers’ approaches to developing a pool of skilled workers, who could be selected to immigrate to Canada and who are ready to begin employment. “This is the next frontier in Canadian immigration: looking at opportunities to attract the best talent and going out there and getting it,” said Kenney.

Meanwhile, across the ocean, Singapore’s immigration policy, according to UNESCO, is one that “maximizes the economic benefits of immigration while minimizing its social and economic costs.” For instance, its early immigration policy emphasized the immigrant’s potential economic benefit, but there was an exclusive criteria for the selection of immigrants whose cultural background matched or was similar to that of the local Singaporean population (e.g., Malaysians). As the country’s labor needs changed, so did its sources of foreign talent. Currently, skilled workers and professionals are sought from different parts of the world, while unskilled workers are predominantly sought from the Asian region.

Under the Singapore Employment Act, a foreigner must have a valid work visa to be able to work in Singapore. Today, the foreign workforce in Singapore is categorized into two broad groups: foreign talent and foreign workers. Foreign talent are skilled employees who have a professional business or educational background, whereas foreign workers are the unskilled labor force.

Skilled professionals and entrepreneurs living in Singapore on a work visa are eligible to apply for a permanent residence in due course. A permanent resident status may be granted within six months to two years, while citizenship eligibility may take up to two to ten years of residence. Unskilled workers on a work visa are permitted to work in Singapore for a certain period of time only and thereafter are expected to return to their home country.

The World Bank, in its report “Doing Business,” consistently ranks Singapore as the easiest country to conduct business, outranking the United States, Hong Kong, and the United Kingdom.

In the United States, few competitions are more cutthroat than college admissions. Yet it might surprise many to learn that Harvard, with its incredible academic reputation and world-class endowment, works hard to recruit students. Each spring it mails a staggering seventy-thousand-plus letters to high school juniors with the best SAT and ACT scores, whom it has identified after buying their names from the College Board. According to Dean of Admissions Bill Fitzsimmons, every year some 70 percent of the students who ultimately attend Harvard are on this list.

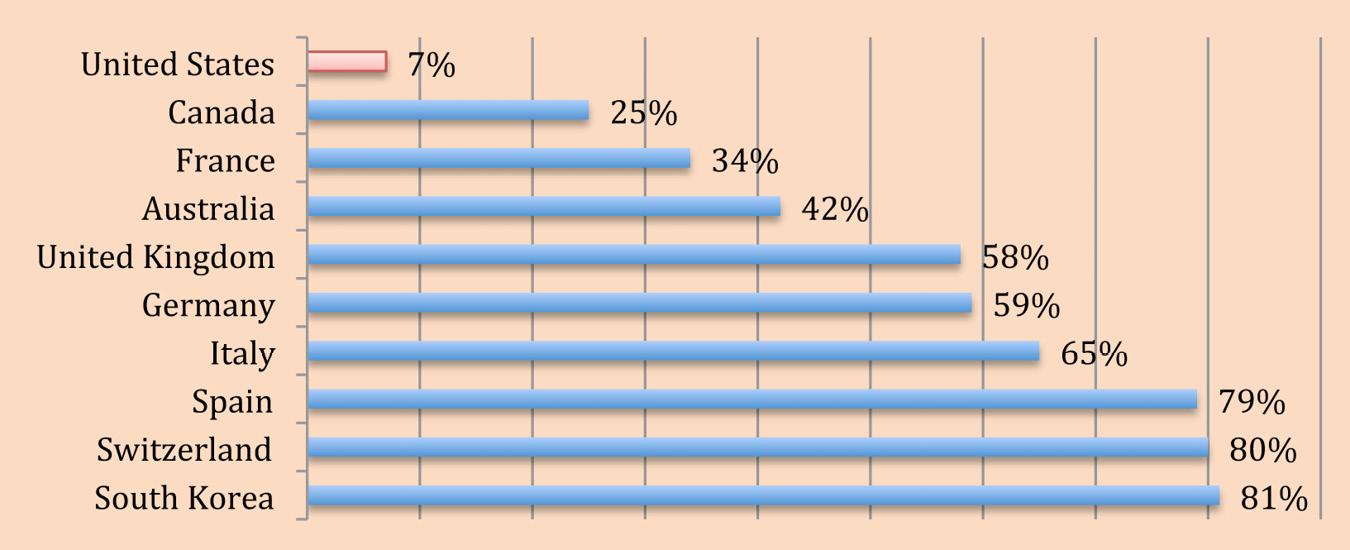

Percentage of Work-Based Immigrants in Various Countries

Pia Orrenius and Madeline Zavodny, “From Brawns to Brains: How Immigration Works for America,” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas 2010 Annual Report,

www.dallasfed.org/assets/documents/fed/annual/2010/ar10b.pdf

.

If our top educational institutions are being proactive in ensuring they elicit the best of the best, U.S. foreign policy should follow their example and assist corporations in identifying and in recruiting the top global talent to contribute to U.S. innovation.

Yet from many prestigious U.S. higher-education institutions, we are sending a large percentage of the already large foreign student body population out of the United States upon graduation. Once we have educated and trained them, they are now equipped to enter the fields of the future. Unfortunately, these fields are also being nurtured and are developing in other locations around the world.

So in looking at how other countries are handling immigration policy, and even taking a page out of our own Harvard and MIT handbook, it seems in a market-driven economy we need to apply some of the same principles to our greatest asset: our people. When thinking of our human capital, it bears repeating, “Capital goes where it’s wanted, and stays where it’s well treated.” Knowledge and skills are the global currency of the twenty-first-century economies.

The most realistic solution for U.S. policy on immigration is to bring the system out of the 1960s and into the twenty-first century by recognizing that, in a global economy, immigration policies must be as responsive to market forces as economic policies. The global contest for talent is likely to define which countries lead the world economy for decades to come.

America was originally built by immigrants, and it continues to be built by the hard work of immigrants. Immigrants are the secret to our success, let’s not forget that.

Woodrow Wilson, in a July 4, 1914, speech at Independence Hall, Philadelphia:

We set this nation up . . . to vindicate the rights of man. We did not name any differences between one race and another. We opened our gates to all the world and said: “Let all men who want to be free come to us and they will be welcome.”

NOTES

1. Vivek Wadhwa,

The Immigrant Exodus: Why America Is Losing the Global Race to Capture Entrepreneurial Talent

, (Philadelphia, PA: Wharton Digital Press, 2012).

2. World Bank, “Global Economic Prospects 2006: Economic Implications of Remittances and Migration.”

3. Garnett Picot and Arthur Sweetman, “Making It in Canada: Immigration Outcomes and Policies,”

The Institute for Research on Public Policy

1 (2011).

4. Paul McDougall, “Microsoft Looks to Dodge Visa Limits with Canadian Software Center,”

InformationWeek

, July 5, 2007,

http://www.informationweek.com/microsoft-looks-to-dodge-visa-limits-wit/200900554

(accessed July 2013).

25

Would I Do It Again?

I

t’s sobering to look back at the choices you have made in your life and their subsequent outcomes and to try to decide what you would do differently if given the chance. I guess everyone by a certain age starts to question the wisdom and validity of their choices. Choices that when made seemed so definitely right, not in the moral sense, but rather in the pragmatic sense. Of course, we are all at the mercy of external forces, regardless of the choices we make or try to make.

Like a feather being carried on the wind, I, too, have been blown around and changed. The life of an immigrant is one of having to survive the tempests that blow in greater force and a more haphazard direction than that of the nonimmigrant. But while I might have a hard time evaluating the wisdom in each decision I have made, I am not able to avoid facing the inevitable consequences that have resulted from those decisions.

We all start out in life as a bona fide member of a tribe, and the unity of a tribe is based on kinship—on kin and kind. It used to be that we rarely encountered someone from another tribe. And, typically, the enemy tribe is the stranger one.

For me, while I have retained close ties with my family, I have lost ties with my kind, for my “kind” no longer exists. This is truly the story of the immigrant. By giving something to his adopted country, he in turn loses a part of himself.

I have regularly met to have lunch with an older group of managers, ministers, ambassadors, government officials, and seniors active during the Shah era of Iran. We discuss U.S. policy toward Iran and comment on its success and failures. After a few meetings, I realized I am no longer an Iranian. I am an American of Iranian decent. During Iran’s green revolution in 2010, I was on TV and in the media extensively. Because of this, along with my background, at the age of sixty I was invited to join a group of highly educated, younger Iranians to discuss and to be a part of the plan for a future Iran. After much thought and consideration, I decided I have become too distant from today’s Iranian culture and society to be part of something that seemed to be the purvey of the younger generation. I guess I felt too established and maybe not hungry enough to hazard it all to gamble on something so uncertain and potentially risky. I had lost the fire in my belly. I could have gone if I really wanted to. But Iran has changed since I immigrated here; I would have probably felt uncomfortable in that environment, and the other members would not have perceived me as a “true” Iranian. Yet I am not just an American. I am also an Iranian, who is well assimilated into this country’s culture and history, its people, and my kin. I am now much older and rooted in the United States. I hope that by mentoring thousands of students I have helped to inspire the next generation, and I can only imagine that my colleagues in education feel similarly. I can only hope that, as immigrants, we have helped to pass the torch onto the next generation of immigrants, who will take up the distinctly American call for those willing to take the risk.

I also can’t help but ask myself what would we, as immigrants, have accomplished, contributed to our heritage, and the world at large, if we had not immigrated. The story of older immigrants as they look back at their lives reminds me of Robert Frost’s poem “The Road Not Taken.”

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could