Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (130 page)

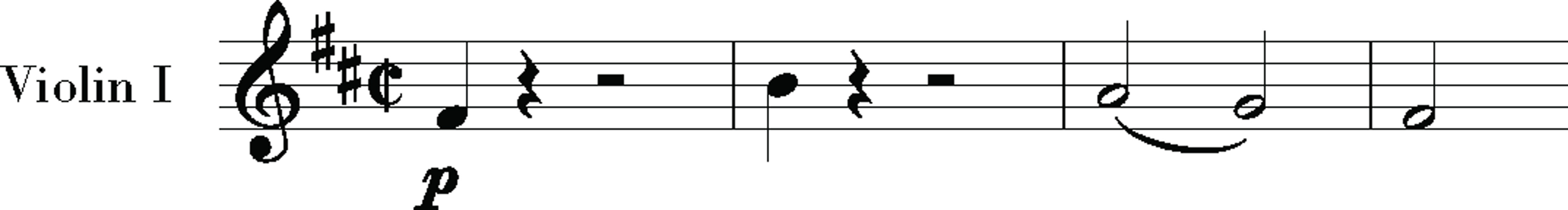

In bars 3 and 4 there are brief chords on the downbeat and then silence. Beethoven was the first composer to make silence a thematic presence beyond a momentary effect, and so it will be in the mass. At the same time, in those two quiet chords placed on silence and the humble, head-bowed phrase that follows it, the violins trace a figure: F-sharpâBâAâGâF-sharp:

Â

Â

That is the prime generating motif of the

Missa solemnis

.

22

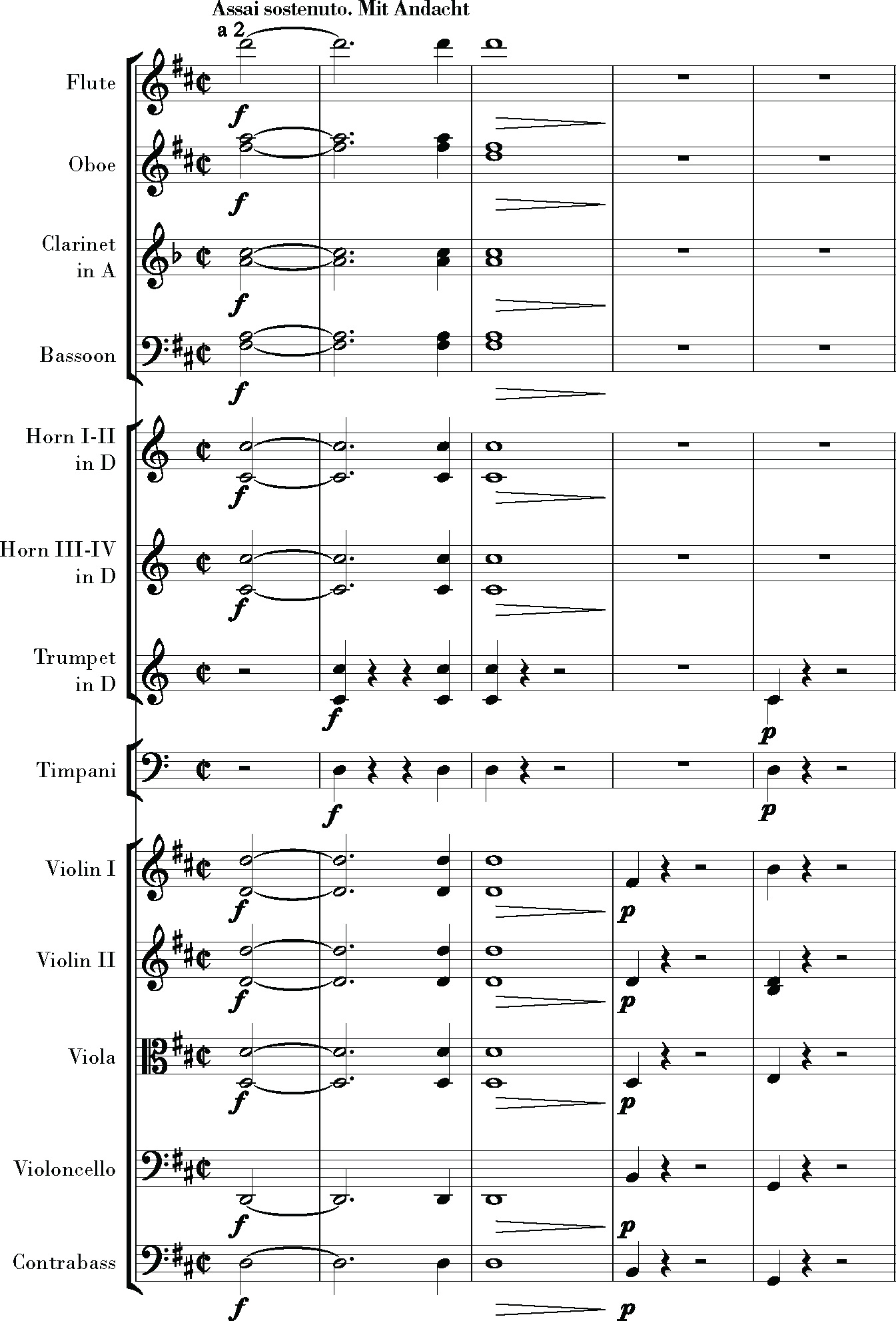

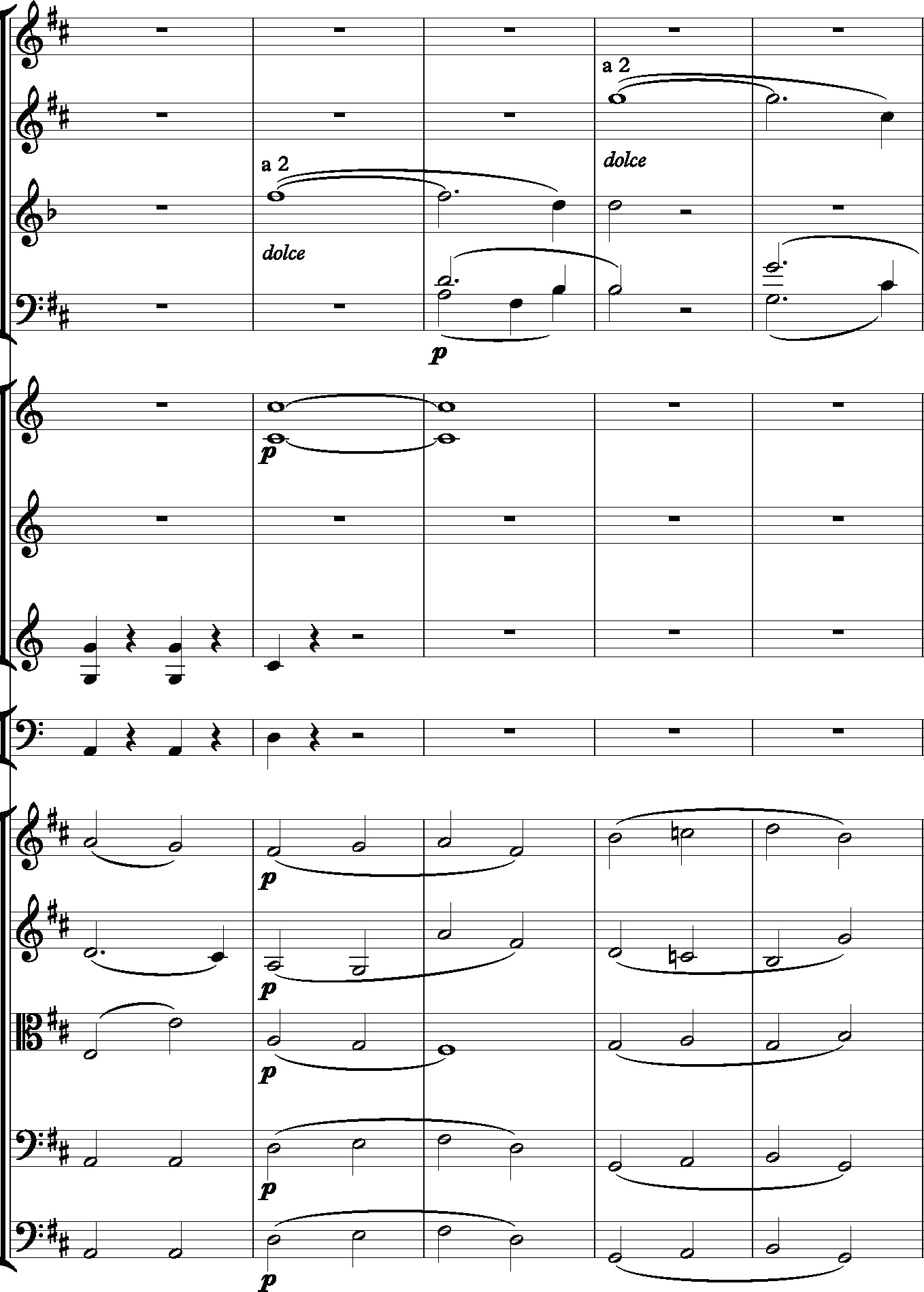

Its myriad forms and permutations are too many to cite, but here are a few:

Â

Â

As usual with Beethoven, the generating motif signifies both as a whole and in its parts. The rising fourth F-sharp to B will mark many themes; likewise the falling line BâAâGâF-sharp. Those last two notes, G and F-sharp, in themselves like a miniature

Amen

, will keep a regular presence. The descent down to F-sharp will echo all the way to the sopranos' last notes at the end: AâGâF-sharp on the word

pacem

, “peace.” The notes AâGâF-sharp outline the primal falling third. So in its course the mass will present a cavalcade of themes, far beyond anything that would be coherent in a symphony. Instead of themes and developments, the music is made from these seed-motifs that continually sprout new themes.

After the opening gestures we hear three calls in the winds: first the clarinet's descending third DâB; in answer the oboe's poignant GâC-sharp; then the flute's AâGâF-sharp (the last notes of the generating motif). All these calls wordlessly intone

Kyrie

.

Â

Â

Â

Â

(The falling-third motif rises from the spoken inflection of the word

Kyrie

.) These woodwind figures establish the principle of imitation, of call-and-response becoming fugue and

fughetta

and

fugato

that enfolds the whole mass. Most of the music will be contrapuntal, the voices constantly echoing one another like an ongoing affirmation.

As far as the text is concerned, the Kyrie's three pleas for mercy from Lord and Christ have in themselves no particular context, dramatic overtones, or imagery. For that reason, composers were traditionally free to interpret them at will, in moods from anguished to magisterial. Meanwhile, in a

Missa solemnis

the Kyrie tends to serve as a kind of introduction to a grander Gloria. Beethoven gave his Kyrie a tone of ceremony and humble devotionâhumility, but not submission. The big opening chord is

forte

, not

fortissimo;

it prefaces music of great gentleness in the first and last

Kyrie

. When the voices enter Beethoven sets up the call-and-response of soloists and choir, the individual and the group, that also will mark the piece.

23

The first section ends with the cadential GâF-sharp whispered on

eleison

.

The

Christe eleison

is marked by a new three-beat meter and faster tempo, its theme a flowing line based on the generating motif. Hereafter, Christ will tend to be represented in lines flowing up and down. The second

Kyrie

returns sounding like a sonata recapitulation, but varied and shortened. The movement ends in a tone of intense reverence,

pianissimo

.

24

In the last two bars Beethoven crossed out the original orchestral doubling and left the choir singing the last syllables quietly alone, an intimate, tender effect that will happen again and again.

25

Always it highlights and intensifies the words.

If the

Missa solemnis

is laid out on a gigantic scale, it is filled with intimate moments like that ending, dozens of them added as Beethoven returned to the nominally completed score. There is sometimes a great deal of complexity in the counterpoint, sometimes more than the ear can fathom, but the expression is always direct and unmistakable. Every note of the

Missa solemnis

is an avatar of the words. That too is symbolic. One ancient metaphor for Christ is

Logos

, “Word”:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God

.

Â

Gloria

Â

The essence of this movement is praise and exaltation:

Gloria in excelsis Deo, et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis

, Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace among men of goodwill. In the New Testament that is the song of the angels announcing the birth of Jesus, the moment of supreme joy in the faith. In this part of any mass the music must be as radiant as music can be. The text moves quickly from one idea to another, all of it addressed to God: We praise, glorify, acclaim, adore you, Lord God, King of Heaven,

Domine Deus, rex coelestis

. The middle, usually a separate and slower section, turns to pathetic entreaties:

Qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis

, Who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy on us. Then, text and music return to praise:

Quoniam tu solus sanctus Dominus

, For You alone are holy, Lord. Often there is a big fugue on the final

Amen;

Beethoven follows that tradition. But after the

Amen

he returns to the

Gloria in excelsis

, partly as coda and partly as recapitulation.

These sections of text and their changing moods are the reason why a mass movement can't be encompassed by sonata form or any other conventional pattern, though it may involve repeated material.

26

Beethoven's layout of the Gloria movement is the traditional fastâslowâfast. Within that broad outline he presents a parade of ideas and themes, each part projecting its particular text: in all some nine distinct themes or ideas, the

Gloria

theme returning within the sections. Toward the end he piles climax on climax, ecstasy on ecstasy, the full orchestra roaring on for page after page. Here as elsewhere in the late music, Beethoven no longer feels obliged to give either performers or listeners a rest but rather mobilizes his singular skill in carrying us to a peak and then to a higher one.

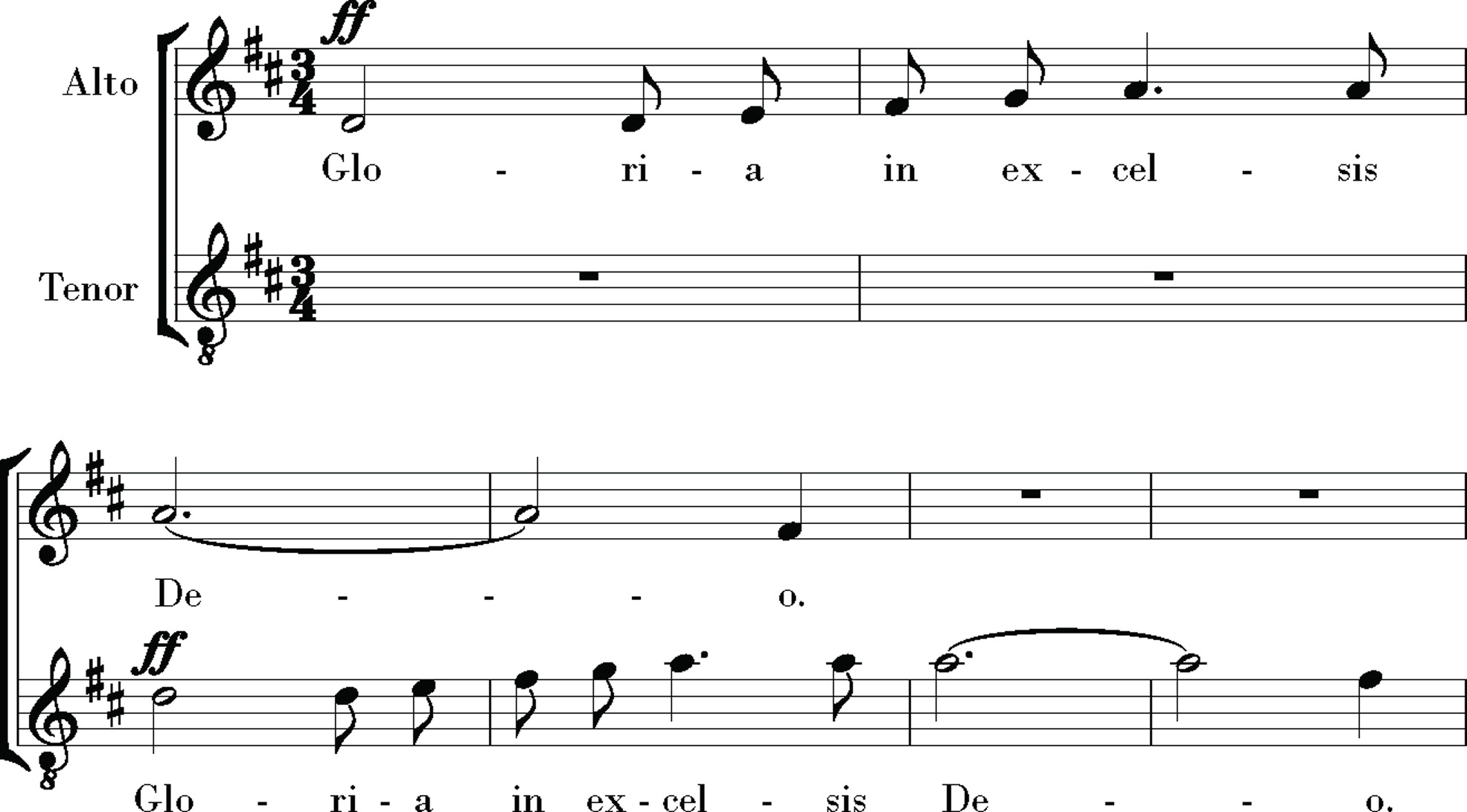

The opening

Gloria

theme in 3/4 and D major is an explosion of exaltation, the horns and trumpets vaulting upward in a figure recalling Handel and the Baroque:

27

Â

Â

Had there ever been a more glorious Gloria? It begins full-blown, with a blaze of excitement, but that will be only a point of departure. The rising

Gloria

theme, meanwhile, pictures this moment in the service when the celebrant raises his arms to express joy. After spine-chilling pages, the music turns in a second to a soft and beautiful evocation of

pax hominibus

, peace to humankind. If the Kyrie amounted to an austerely devotional introduction to this quasi-symphonic mass, the blazing Gloria is the first movement proper. In its course, starting with the turn from

gloria

to

pax

, it reveals how Beethoven is going to build a sectional form founded on minute picturing of the text.

Laudamus te

, we praise You, breaks out using the

Gloria

figure, now offset to begin on the third beat of the bar.

Adoramus te

, we adore You, is another sudden

pianissimo

, evoking the moment where the celebrant bows his head.

28

(If the mass ultimately goes beyond the church and its priests, aiming toward God without intervention, it nonetheless encompasses visceral images of the Catholic rite even as it transcends them.)

Glorificamus te

, we glorify You, is a short vigorous

fugato

on a leaping subject. With a hushed turn to B-flat major, the soloists lead a brief

Gratias agimus tibi

, we give thanks to You for Your great glory. With the arrival of

Domine Deus, rex coelestis

, Lord God, King of Heaven, Beethoven mobilizes the hard

d

's of the Latin for cries of adoration, building to a tremendous triple-

forte

chord on

omnipotens

, omnipotent.

29

The tempo slows to

larghetto

for the middle section, introduced by the winds to prepare pathos-filled entreaties:

Qui tollis peccata mundi

, Who takes away the sins of the world, Who sits at the right hand of God, have mercy on us. Here Beethoven concentrates on

miserere Ânobis

. The words are whispered over trembling figures in the strings and keened by the soloists; they mount to an anguished entreaty.

Quoniam tu solus sanctus Dominus

, For You alone are holy, Lord, starts the third section with a virile theme conjuring the power of God. In the climax the trombonesâa sounding image of God's powerâenter for the first time.

30

In another quick turn of tempo and mood, the grandest and most vigorous fugue yet breaks out on

in gloria Dei patris

, in the glory of God the Father. (The choral lines are accompanied by trombones, the players' struggle to manage their scampering parts adding to the intensity.)

31

That fugue is marked

allegro, ma non troppo

âfast, but not too muchâbut even then it is plenty awkward for the singers. The climax of that section begins with an

Amen

marked

poco più allegro

, a little faster, at which point the music becomes manifestly too much: in a double fugue the

Amen

figure is combined with the

in gloria Dei patris

theme, both heard right-side up and inverted, at speeds verging on unsingable.

32

That mounts to yet another climax, vertiginous for listeners, its cries of

Amen!

playing dazzling tag with the meter.