Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (133 page)

What has happened? Generations will debate it, often trying to make the end into a pious and affirmative conclusion. But if Beethoven has put away many of his habits of development and musical logic in this work, he has not abandoned cause and effect, proportion, underlying logic, even when he intends to violate them. The war interludes break out around the rite, interrupt the service, shatter the peace, tear apart the form. The peace, the form, never recover their equilibrium.

In musical terms, with the sounds of war, Beethoven injects an alien and unprepared but overwhelming dramatic force into the music, in the same way that his thunderstorm once broke up a peasant dance in the

Pastoral

. This is a logic of image and narrative, not music. By the laws of music that Beethoven bent and adapted but never lost sight of, a new idea has to be integrated, the disruption it created has to be resolved. In the

Pastoral

Symphony the resolution is a peaceful, thankful finale. In the Eighth Symphony finale, the disruption of the intrusive C-sharps is resolved in a farcical outbreak of modulations at the penultimate moment.

In Beethoven's Agnus Dei, there is no integration and no resolution of the violence and disruption. The rumbling of drums at the end pictures war receding, at the same time reminds us of our terror. At one point Beethoven sketched a triumphant ending, labeled the receding-drum idea

peace

. Then he decided that, no, to finish this gigantic work of faith he wanted a curt, ambiguous, unresolved ending.

A work of faith it is. But in the end the

Missa solemnis

is Beethoven's personal faith as an individual reaching toward God, not an assertion of the credos and dogmas of the Holy Roman and Apostolic Church. He subsumes doctrine in some degree, as he must in order to write a mass at all, but he goes beyond doctrine into a unique mingling of faith, spirituality, and humanism. He created a mass that subsumed the doctrines and the physical rite of the church, the very gestures of the priests and the preluding of the organist, but he turns them into something both personal and universal.

53

Ultimately the

Missa solemnis

is a statement of faith and also of doubt, beyond the walls of any church.

From the heart, may it go to the heart

âperson to person, without priests. The

Missa solemnis

is Beethoven's cathedral in sound.

At the end there is no triumph of faith, no triumph of peace, no triumph at all. God has not answered humanity's prayers, its demands, its terrified pleas for peace. The drums have receded, but they are still out there, and they can come back. Beethoven's most ambitious work, his cathedral, the one he intended to be his greatest, ends with an unanswered prayer. What, then, is the answer? Whether he planned two successive works as a question and answer, or whether it happened because Beethoven was who he was and believed as he did, his answer was the Ninth Symphony.

31

F

OR BEETHOVEN THE

Ninth Symphony in D Minor, op. 125, had a long background. It marked a return to roots in his life, his art, and his culture. Those roots reached back to his youth in Bonn during its golden years of Aufklärung, when he first determined to set “An die Freude,” the Friedrich Schiller poem that in fiery verses embodied the spirit of the time. The intellectual atmosphere he breathed in Bonn included the philosophy of Kant, the Masonic ideal of brotherhood, the Illuminist doctrine of a cadre of the enlightened who will point humanity toward freedom and happiness. Passing through his life and awareness in the next decades were the French Revolution and its art, the funeral dirges and music for public festivals; then the wars and the burgeoning hopes of the Napoleonic years; then the destruction of those hopes and the end of the age of heroes and benevolent despots.

Also simmering within the Ninth Symphony as it took shape was the model and the threat of Haydn, who wrote

The Creation

and the song that became the unofficial Austrian national anthem. Beyond Haydn lay traditions and voices and models that Beethoven had always turned to for ideas and inspiration: Handel, Mozart, Bach, and the history of the symphony, including what he himself brought to that history.

Once, the threads of his early years had gathered into the

Eroica

, which secured the symphony for more than a century as the summit of musical genres. Now the accumulated threads of a lifetime converged to create the Ninth, the sister work to the

Missa solemnis

, the answer to the human and spiritual question that the mass left hanging: if God cannot give us peace, what can? Beethoven did not consider the mass and the Ninth his final statements, because he hoped to write still greater works if fate gave him the chance. Fate did not oblige. So if the mass and symphony were not the end, in many ways they were the summation and culmination of his life and work.

The Ninth itself took at least a decade to condense from its first vague imaginings, during anguished and drifting years, to the conception that it became: a monumental symphony whose culmination is a finale with the unprecedented inclusion of a choir and soloists singing verses from “An die Freude.” As it took shape, the music of the symphony itself traces that same journey from vaporous beginnings through tragedy to triumph.

Â

When in his teens Beethoven declared to friends his intention of setting the whole of Schiller's “To Joy,” one of his adult admirers wrote to Schiller's wife, “I expect something perfect, for as far as I know him he is wholly devoted to the great and sublime.” If Beethoven attempted that setting at all, any traces of it disappeared; several years later, he suppressed another setting that he had mentioned to a publisher. But he never stopped thinking about the poemâhe remembered it after Napoleon betrayed the republican dream, and after Austria set out to erase the memory of that dream. Since the 1780s there had been some forty settings of “An die Freude,” including one from 1815 by the young Franz Schubert.

1

They were widely sung in Masonic and Illuminati lodges. Most of these settings were, like the poem itself, in the tradition of the

geselliges Lied

, a social song intended to be sung by groups of friends.

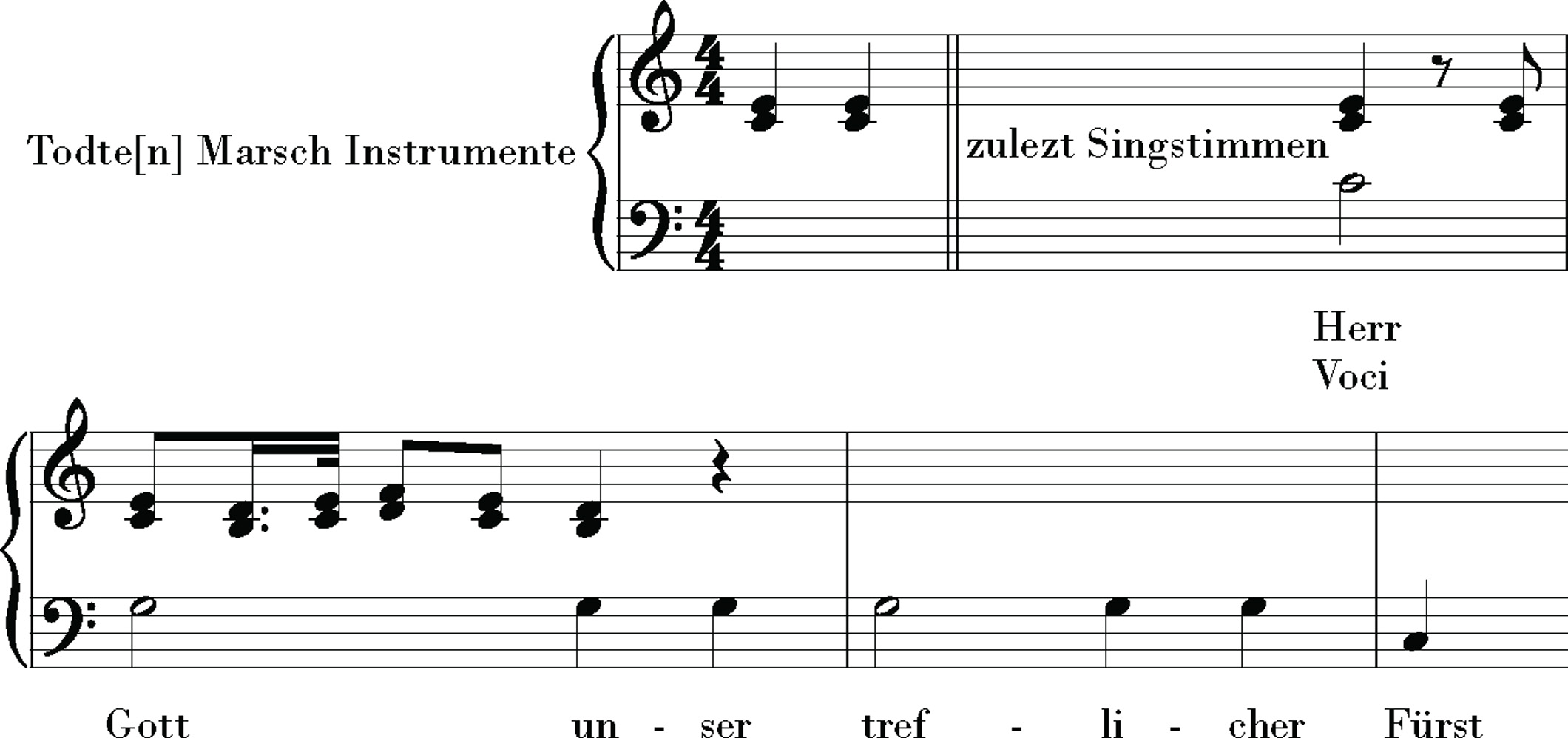

Ideas about a “Freude” setting and/or a work with chorus, perhaps as part of a symphony or some sort of freestanding piece, began to turn up in Beethoven's sketches of the middle teens. In early 1816 he added one more sketch to his dozens of ideas for symphonies:

Â

Beethoven

Â

This is one of his few symphony sketches that eventually took wing. It is recognizable as the opening of the eventual Ninth. More sketches turned up in the winter of 1817â18, also involving what became central ideas. One of them was a string tremolo on the open fifth AâE, the essential concept of the beginning. Loose, abortive ideas for the second-movement scherzo appeared, written beneath one of them, “Symphony at the beginning only 4 voices 2 Vln, Viol, Bass among them forte with other voices and if possible bring in all the other instruments one by one.” Sketches toward what became the slow movement may first have been intended for a different piece.

2

By around 1818 he had fixed on the idea of a symphony with voices to enter in the finale or earlier. He was also thinking about the archaic church modes, though those ended up mainly in the mass and a late quartet. He speculated about the music from a slow movement returning in the finale, also an ecclesiastical touch and a Bacchic (meaning dancing and ecstatic) movement. Around the same time he wrote in his

Tagebuch

, “To write a national song on the Leipzig October and perform this every year. N.B. each nation with its own march and the Te deum laudamus.”

3

Here he imagined some sort of national work for an international festival. In one way and another, all these ideas ended up in the Ninth.

After what appears to be a long hiatus came a few bars of ideas including, from 1822, a sketch toward variations on Handel's well-known

Funeral March

from

Saul

. The snippet of the Handel march Beethoven jotted down is a precursor of the coda of the Ninth's first movement:

4

Â

Beethoven

Â

That year he sketched a simple, almost chantlike setting of “An die Freude” with this note: “Sinfonie allemand after which the chorus enters or also without variations. End of the Sinfonie with Turkish music and vocal chorus.”

5

So by that point he was thinking about a symphony to end with a choral setting of “An die Freude” involving music in the pseudo-Turkish style familiar in military music.

All these loose ideas, of the kind that characterize most of his jottings in the sketchbooks, precipitated into intensive work in the spring of 1823. By then two things had happened. In November 1822, the Philharmonic Society in London accepted his proposal to write a symphony for it, offering 50 pounds; and he finished the

Diabelli

Variations and had nothing else pressing to do. The London commission was yet another impetus to go to England and see whether he could duplicate Haydn's triumphs. Around April 1823, new sketches and drafts for the symphony followed on the completion of the

Diabellis

.

6

Some eleven months later, the Ninth was done.

When he got down to the job, he already had what amounted to a final conception of the opening. But he had a problem that needed to be addressed before he went further. He was determined to make this an end-directed symphony, that end being a choral finale involving voices and “An die Freude.” As he said,

Always keep the whole in view

. If the finale and its theme were to be a goal, the music needed to foreshadow it from the beginning. So before he got too far into the first movement, he had to find his finale theme. In that respect the symphony was going to be composed back to front, as the

Eroica

and the

Kreutzer

Sonata had been: the leading ideas of the beginning being developed from the main theme of the finale.

Quickly he found his opening phrase for the poem:

Â

Â

For the moment, though, that was all he found. The rest of the theme, which would encompass each of his chosen verses of the Schiller (selected from the much longer complete poem), would not come. But in fact the inception of the theme was all he needed, for the moment, to make his foreshadowings. The first phrase could stand for the whole of the

Freude

theme, just as the first notes of the

Eroica

theme often stood for the whole. He could finish the rest of the finale theme later.

At the same time, that first phrase, setting the first four lines of the Schiller, determined the style and direction of the

Freude

theme. It is above all simple, an ascent from the third degree of the scale to the fifth and back down to the first degree, all in quarter and half notes. Here Beethoven's longstanding concern with simplicity and directness found its ultimate distillation in a little ditty that was going to be the foundation of a monumental work. That ascent from the third degree to the fifth and scalewise back down to the first would be the essence of the foreshadowings in the symphony. So strong was that presence that it took him considerable pains, when he finally got to it, to finish the tune in the same plainspoken spirit while giving it at least a little seasoning.