Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (134 page)

Beyond that, what did he have in mind as he shaped the

Freude

theme from its seminal first phrase? He already understood that the finale and its theme were going be the goal, the destination. Which is to say, the symphony was going to be a journey toward joy, starting in despair. It was a familiar narrative for Beethoven; he had done something like it in the Fifth Symphony. And he knew what he was aiming for in the

Freude

theme itself: a tune in the simple, popular, rhythmically and harmonically straightforward style of a

geselliges Lied

, especially the kind the Freemasons used to sing (before they were banned in Austria).

In all this he was doing what he usually did, taking models and expanding them in his own directions, sometimes expanding them exponentially. One model was his own

Choral Fantasy

for piano, voices, and orchestra. Beethoven himself described the finale of the Ninth as in the vein of the

Choral Fantasy

. The leading themes for both pieces have the kind of straightforward, declamatory style of other of his songs on echt-Aufklärung texts going all the way back to

Who Is a Free Man?

from his youth (which his Bonn friend Wegeler turned into a Masonic song).

In turn, part of that style was the

geselliges Lied

. Those sociable songs, intended to be proclaimed in company with glass in hand, were always strophic, meaning each verse was sung to the same tune. Generally the songs exalted friendship, fellowship, brotherhood, and joy.

7

One example is Beethoven's own

Bundeslied

(Song of the Confederacy), on Masonic verses by Goethe. It begins: “Whenever the hour is good, / Inspired by love and wine, / Shall we, united, / Sing this song!” On the manuscript Beethoven noted it was to be sung “in companionable circles.”

8

On a larger scale was the memory of French revolutionary music that had been a major inspiration of the

Eroica

. These were pieces for public festivals that had a style at once popular and monumental. Here art became a communal ritualâin France largely to nationalistic and propagandistic ends, but artists had a deeper agenda. Poet Marie-Joseph Chénier wrote, “The ability to lead men is nothing else than the ability to direct their sensibilities . . . the basis of all human institutions is morality, public and private, and . . . the fine arts are essentially moral because they make the individual devoted to them better and happier. If this is true for all the arts, how much more evident is it in the case of music.” Robespierre wanted to teach a specially written “Hymn to the Supreme Being” to every citizen so all Paris could sing it at an outdoor festival.

9

Another piece of the background was the relatively new idea of national anthems, their tunes designed to be inspiring, memorable, easily singable by the multitudes. Haydn had been inspired by the British

God Save the King

when he was commissioned to write

Gott Âerhalte Franz den Kaiser

, which became the unofficial Austrian anthem. Haydn went on to write variations on the theme in his

Emperor

Quartet. (Beethoven also admired

God Save the King

and used it in piano variations and in

Wellington's Victory

.) Beethoven surely envied Haydn his anthem. Another model, most potent of all, was

La Marseillaise

, the indispensable song of the French Revolution that set feet marching to overthrow the ancien régime and attached itself to the revolutionary spirit everywhere. (That is why, after he crowned himself emperor, Napoleon banned the

Marseillaise

. Revolutions were to end with him.)

So a trajectory in Beethoven's work began in Bonn, rose to its apogee in the Third and Fifth Symphonies and in

Fidelio

, and came to rest in the Ninth Symphony, which resonated with the accumulated political and ethical ideas and energies of the previous decades. The

Eroica

exalts the conquering hero;

Fidelio

is a testament to individual heroism and liberation; the Fifth Symphony is an implicit drama of an individual struggling with fate. The

Eroica

and the Ninth have to do with the fate of societies. As to the road to an ideal society, the Ninth repudiates in thunder the answer of the

Eroica

.

No wonder that it cost Beethoven some trouble to finish the

Freude

theme after arriving at its opening phrase. By the time he needed the complete tune to compose the finale, he had gone through nineteen stages of work on it, mostly for the second part, which adds the seasoning of a leap to a note tied over the bar.

10

A great deal was riding on this theme, not only the direction and fate of his most ambitious symphony but matters well beyond that. He intended the theme to be his

God Save the King

, his Austrian anthem, his

Marseillaise

. But those anthems were devoted only to nations. His ambitions for his tune had expanded exponentially. He wanted to write a universal anthem, a

Marseillaise

for humanity.

11

To that end he demanded of himself that he create a popularistic theme like something that had written itself, an ingenuous little tune that everyone could remember and nearly anyone could sing.

12

He wanted a theme to conquer the world.

13

Â

The Ninth Symphony begins in mist and uncertainty, on a hollow open fifth and the wrong harmony: winds and string tremolos on A and E. The A seems to be the keynote, but it isn't. The sound of the beginning, like matter emerging out of the void and slowly filling space, had never been heard in a piece before. Yet its effect was familiar to the time: the beginning of the Ninth is a descendent of “Chaos” in

The Creation

. Haydn's “Chaos” resolves into the C-major revelation of

Let there be light!

The chaos of the Ninth's beginning resolves into a towering proclamation of forbidding import, the orchestra striding in militant dotted rhythms down a D-minor chord.

14

D minor for Beethoven was a rare key, usually fraught: the

Tempest

Sonata; the tragic slow movement of the Piano Sonata op. 10, no. 3; the

Ghost

Trio second movement.

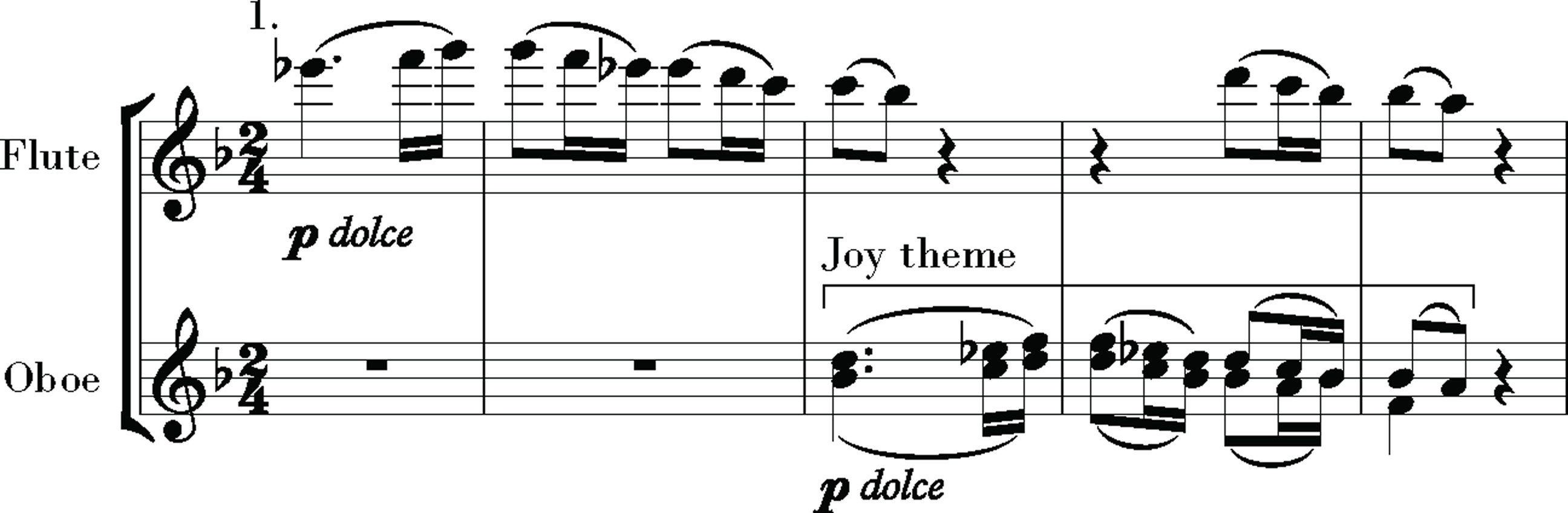

In the Ninth, the gestures that emerge from the void are stern and heroic, at the same time gnarled, searching, nervous, remote. If this is some kind of heroic image, it is a hero whose proclamations are raging and indisputable. What will prove to be the leading theme and motifs are first heard in measures 19â20:

Â

Â

This is hardly a melodic idea; call it one of Beethoven's “speaking” themes. The rhythmic motif,

da-da-da-dum

, is of course essentially the same as that of the Fifth Symphony and any number of other Beethoven works. Another steady presence in the movement is the militant tattoo of dotted rhythms. The descending three-note bit of scale is the opening motif, inverted, of the

Freude

themeâa first, distant prophecy.

At the same time this beginning that emerges from nothing, filling in space, rising to a gigantic proclamation, suggests another metaphor that pervades the symphony. The beginning is an image of creation itself, of the creation of worlds, of societies, of individuals. It brought to music the idea that a work can evoke a self-creating cosmos. The beginning also involves

the creation of a theme

, which will eventually be the main business of the first part of the finale. Lying behind that is an image of the Ninth Symphony rising from silence

to create itself

, as a work rises from nothing in the mind of its creator. The last movement will return to that image. These images all work together. To say again: with Beethoven emotion, drama, image, and technique work in harmony (most of the time). Not only is the image of creation a fundamental idea and message of the Ninth Symphony, it is a central part of its effect.

This is the most complex first movement Beethoven had made since the

Eroica

, and a far more enigmatic opening than that symphony's. As in the earlier work, the first movement is based on fragments more than sustained themes. Here the texture is filled with bits of ideas constantly batted around the orchestra. Which is to say that, like the

Eroica

, it is developmental from the beginning, the exposition of the sonata form vibrating with the restlessness of a development section.

In keeping, it has the late period's tendency to float the harmony. After the first pages, there is no strong cadence to D minor until measure 429; this is the home key not as a foundation but as a long-awaited, hard-won goal. For long stretches there is no clear cadence at all. Such floating, unresolved harmony can create a feeling of suspension and reverie, but here it sustains an unrelenting tension.

15

Part of the effect is that much of the time the basses are restlessly in motion, in scales and arpeggios and melodic lines, so the harmony has no solid foundation. The movement avoids the usual secondary keys related to D minorâF major and A minor or major.

In their formal import the first two pages are ambiguous: is the AâE tremolo a theme or an introduction? What about the D-minor arpeggio theme? (As it plays out, the tremolo is not developed in the movement like a theme, but the arpeggio is.) The tremolo returns on DâA for a moment, stabilizing the harmony briefly, for the last time in a long time. Then two things of considerable import happen. First, the stern arpeggio theme recurs in B-flat. Second, the three-note descending motif from the speaking theme in measure 19 begins to be treated obsessively, first in a nervous alternation of D minor and D major. Those three tonalitiesâD minor, D major, B-flat majorâare going to be the principal tonal areas of the symphony. Throughout there will be a dialectic between D minor and major. D minor was for Beethoven often an ominous key, D major associated with gaiety, comedy, joy. And as in the Fifth Symphony, major is destined to win out over minor in the finale.

In a sketch, the emotion Beethoven applied to the first movement was despair. Its tone is not like the portraits of despair in his music going back to

La Malinconia

in op. 18 and the

Pathétique

and

Appassionata

. In the Ninth the despair is something unfamiliarâunbending, elusive, relentlessly unstable. The tone of the music is close to Beethoven's heroic style, but the instability questions that style and that ethos.

As with the

Eroica

, the second-theme section of the sonata form is complex, full of ideas, ambiguous as to where it begins. Just before the second theme there is a sudden lyrical warming, a brief, harmonically stable moment in B-flatâunmistakably a moment of hope. Melodically and rhythmically, this is the first clear prophecy of the

Freude

theme, beginning with its three-note bit of ascending scale:

Â

Â

The warmth persists through the next phrases, the second theme proper. Then restlessness seeps back in. That moment of hope in lyrical B-flat is not truly part of the form; it is an interjection, an anomaly. It does not return until the recapitulation, and only that once.

16

The end of the exposition is the down-striding dotted-arpeggio theme in B-flat. That is the first truly stable harmonic moment since the opening pages. From there we hear what seems to be the usual repeat of the exposition, returning to the tremolo strings on AâE. But it is a false repeat. For the first time in a symphony, Beethoven goes on without repeating the exposition.

The development section, usually the most turbulent part of a sonata-form movement, is here the most relatively calmâthough there is still an undercurrent of tension. It begins with a look back at the descending-arpeggio figure, now quieted. Nearly every phrase is a tidy four bars. But from the exposition he has hardly any normal theme to develop, so now he uses the leading motifs to create more sustained themes. Between that and the lack of an exposition repeat, he is aiming for a through-composed effect, the material constantly in flux, forming and reforming in new directions, self-creating. There are loud, vigorous moments in the development, but no shattering climax as in the

Eroica

. The shattering moment is the recapitulation.