Brain Trust (11 page)

Authors: Garth Sundem

First, the basics. In homage to the Naval Academy, think about basketball as ballistics. You’re blasting a projectile that travels up and then down, while also traveling horizontally, describing a parabola from your hand to the hoop (ideally). In basketball’s case, the higher the arc, the more straight down the projectile travels as it nears the hoop, and thus the bigger the target looks (you already knew this). But the shortest distance between two points is a straight line and so the higher the arc, the longer the shot’s total distance and thus the more precise it has to be leaving your hand (error is magnified over distance).

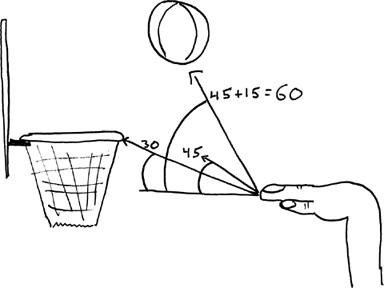

So there’s an optimal angle of release—one that balances the desire to drop straight down at the hoop with the desire for a short, overall path. What’s the balance? Another physicist, Peter Brancazio of Brooklyn College, used some nifty trig to show that due to the size of the ball and the surface area of the hoop, any angle shallower than 32 degrees hits the back of the rim. The angle that gives the most margin for error is 45 degrees plus half the angle from the top of the player’s hand to the rim.

Imagine this angle: You’re hanging in the air, hand extended—draw a line from your fingers to the rim. Now scoot this frozen-in-time jump shot closer to the rim. As the hand gets closer, the angle gets steeper, and as you move the hand out past the three-point line, the angle of the line connecting fingers to rim gets shallower. This makes the ideal angle of a shot from just beneath the rim almost straight up and a long-range jumper almost exactly 45 degrees. It also means that a shot released above the rim can be shallower still, subtracting half the angle between fingers and rim from the balance point of 45 degrees.

Practice it from different distances—a shallower shot from farther out, but assuming you’re releasing from below the rim, never less than 45 degrees.

Another problem that Fontanella points to with a high-arc shot is that of approach speed. “A good shooter minimizes the ball speed at the basket,” he says. “That’s a soft touch.” On the off chance that your perfectly angled shot catches metal, you want it to grab like a golf ball catching the green, bouncing around in the small, defined cylinder above the basket where it has the greatest chance of rolling in. And like golf, a big piece of a soft touch is backspin. Simply, it takes speed off the ball and keeps it in the cylinder.

Finally, with about 359 degrees around you where the ball won’t go in the hoop and only about one degree where it will, randomness isn’t in your favor. And any aspect of your shot that increases randomness is an aspect that hurts the chance of success. “The really good shooters do it the same every time,” says

Fontanella. Good shooters land in the same place they took off, and they release the ball at the jump’s apex, meaning they’re traveling neither side to side nor up and down at the instant the ball leaves their hand. It’s a perfectly still moment in time, with no random movement that creates drift. To see randomness in action without a jump, look at a Shaquille O’Neal free throw. The arm never travels the same path twice.

On the other end of the spectrum, if your memory can’t call up a snapshot of Reggie Miller hanging in the air like a plumb bob with his shooting arm extended at 50 degrees, find a vid online.

That’s how to be a baller.

Puzzle #5:

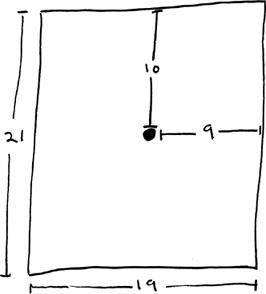

Tramp Trouble

And with that geometric refresher, imagine the following dilemma: It’s Christmas Eve day and the trampoline your in-laws shipped to you—which you’d meant as the holiday gift centerpiece—is too big for your condo’s porch. But if it weren’t for that darn support pole in the middle of your garage, the trampoline would fit in there easily. Hey, maybe it will still fit! Can you possibly, possibly somehow stuff a trampoline with a 12-foot diameter into the two-car garage shown on the next page, thus saving Christmas?

Why do bees give away meat or defend other bees at cost to themselves? Doesn’t this behavior decrease the likelihood of Mr. Care-and-share bee passing on its let’s-all-hold-hands-and-sing-“Kumbaya” genes? Doesn’t evolution prune these pinko hippie bees from the genetic tree of life? “Altruism drove Darwin crazy,” says Lee Alan Dugatkin, biologist at the University of Louisville and author of

The Altruism Equation

, “but the answer is deceptively simple.”

Whether or not you help someone in need comes down to three factors: (1) how much it costs you to help; (2) how much the person gains by your help; and (3) your genetic relatedness to the person in need.

This is the altruism equation: r × b > c. If relatedness times benefit outweighs cost, then you help. You’d throw yourself in

front of a train to save two of your siblings or eight of your cousins, but not one of your sibs or seven of your cousins. This is because, on some level, you recognize that a sibling has half of your genes—saving two brothers passes on the equivalent of your genetic material. Same with eight cousins. Similar might be true of an airplane full of people of your ethnicity, or a cruise ship full of people from all over the world. Altruism makes sense “if you can somehow make up for the cost of being altruistic by increasing the chances that your genetic relatives survive and reproduce,” says Dugatkin.

Anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon famously studied this relationship of altruism and kinship among the Yanomami of Venezuela. From the mid-1960s to late 1990s, when Chagnon lived with the Yanomami, they were into all sorts of nifty things like periodically banding together in ever-changing alliances to cut off heads, shrink them, eat people, etc. Chagnon almost lost his noggin more than once, but survived to compile extensive genealogies of the Yanomami, showing interrelatedness among the many widely dispersed tribal groups. And what he found is a clean (inverse) correlation between relatedness and the likelihood you’ll chop off and shrink someone’s head and/or eat them. Even without prior knowledge of kinship, the Yanomami somehow knew not to eat family.

“I think the human psyche has been designed to pick up clues that come from gene expression,” says Dugatkin. Certainly, studies have shown that we’re very, very good at recognizing people we’re related to, even without having met them before. What cues this recognition? Is it genetic? “Even the evolutionary biologists are trying to develop models of culture in which the gene is not the central player,” says Dugatkin, “but this thing called a meme that represents information is the unit that selection operates on.”

So, the theory goes, when we instantly recognize a long-lost relative in a lineup, it’s not that we somehow intuit this relative’s

genetic makeup—it’s that we similarly intuit memes, or the many signals not only of genetics but of cultural similarity, including Aunt Joan’s clipped “T’s,” Great Uncle Wilbur’s habit of winking as punctuation, and Grandpa Gary’s bad sense of humor that makes one pepper terrible puns throughout a book of scientific tips.

This reliance on memes rather than genes to determine relatedness bodes well for your ability to fool others into being altruistic toward you—to, for instance, make them give you money—for while it’s rather cumbersome to change your genetic structure to be more similar to that of a person you’re hitting up, changing your memetic structure—the ways you signal genetic similarity—is totally doable. “There are ways to create the illusion of genetic relatedness among people,” says Dugatkin. “Look at the military or religious organizations referring to people as brothers.” This language creates false kinship … and people in these organizations help one another.

Further evidence for the power of kinship language comes from another sort of evolution. How many lines do you think a panhandler tries in a career of begging? And why do you think some lines become more used than others? Because they work, that’s why—the others are selected against. And what’s the stereotypical, clichéd panhandling line? It’s “Brother, can you spare a dime?” By implying relatedness, the panhandler thumbs the scale of the altruism equation and makes it in your genetic interest to give (remember: Relatedness times benefit must outweigh cost).

And if you’re going to try to get money or other aid out of a population, you’d do well to walk like them and talk like them too. “We use similarity as a proxy for kinship,” says Dugatkin, “and the slightest indication of relatedness can stimulate altruistic behavior.” If you want money from your uncle, be sure to use Aunt Joan’s clipped “T’s” when making your request.

So you can influence the perception of relatedness.

Next let’s look at cost (again, not to beat it over the head or anything, remember: r × b > c).

You know the saying “It’s better to give than to receive.” While this is so obviously parent-speak for “For God’s sake just give your little sister the My Little Pony Tea Set!” it contains at least an element of truthiness. That element is the fact that we can gain by giving. A person might not gain money by giving you a dime (or they might, in the long run, due to reciprocity, but that’s another long scientific story), but instead they might gain the admiration of a date, or giving a dime might allow your target to feel like a swell fellow. Or hold a sign that gives a laugh in return, like ninjas killed my family. need money for kung fu lessons! Or think of the broader meaning of “cost.” To a well-dressed woman in a business suit, a dollar may have the same “cost” as a dime to you and (especially) me.

Or think about the perceived worth of money: A quarter seems useful, while a dime is the first denomination that, for whatever reason, seems worth less than its face value. In other words, it seems like it costs $0.35 to give a quarter, while it only costs about $0.07 to give a dime. We’re back to the logic of “Brother, won’t you spare a dime?”

Finally, it also matters how much this dime would benefit you. Imply that it will save your life or at least provide the tipping point into something tangible like a sandwich or a bed or a beer, and you’re more likely to get what you need.

So if you’re asking for anything—your boss for a raise, your parents for a car, or a stranger for a handout—imply relatedness, decrease the cost of giving, and promise massive personal benefit to tip the scale of altruism in your favor.

In his book

Mr. Jefferson and the Giant Moose

(surprisingly, not a children’s title), Dugatkin tells the story of the French notion that the fledgling United States was populated by underevolved, inferior, weakling species. To counter this ethnocentric arrogance, Thomas Jefferson had the skeleton of a seven-foot-tall moose shipped first-class from New Hampshire to Paris.

Researchers at Washington State University

found that across a number of studies, instead of applauding people who contributed more than their fair share to a group while taking little in return, other group members wanted to kick the do-gooders out entirely. Reasons include making others look bad, setting an example that others would rather not have to follow, and simply acting contrary to established social norms. So if you’re a natural angel, find a little devil to express or risk being shunned.