Brain Trust (13 page)

Authors: Garth Sundem

Cool: cost of initiation must outweigh potential gains of betrayal.

But what about recruiting your posse in the first place? There’s another thing these top four terrorist organizations—Hamas, Hezbollah, al-Qaeda, and the T-ban—have in common: “They all started as mutual aid societies,” says Berman. They provided services in communities that lacked them. And with limited resources, clubs had to learn how to be exclusive—they developed and tested initiation rites as signals of commitment, and wove club membership deeply into communities, families, and the fabric of culture.

Contrast this with the would-be terrorists known as the Toronto 18. They played soccer together—oh, and plotted the beheading of the Canadian prime minister. Word leaked and soon the group accepted a new member, Mubin Shaikh—a police plant who hung out until gathering enough evidence to arrest the lot of them.

Their downfall? They didn’t require a signal of commitment, and their connection to each other was topical, rather than growing from mutual support ingrained in culture.

What this means for your posse is this: first, make yourself indispensable in a benign way, creating an exclusive club with membership benefits. Then require a stout initiation rite.

Only then will you have snitch-proof henchman capable of carrying out your supervillainy.

Can you guess how Eli Berman recommends

squishing terrorist organizations? “Competent governments must provide social services,” he says, thus removing the need for independent aid societies—the societies that can so successfully turn violent. Eli Berman is the research director for international security studies at the Institute for Global Conflict and Cooperation, and author of the extremely cool book

Radical, Religious, and Violent

.

Do you want to find a friend of a friend who

plays cricket, World of Warcraft, and speaks Cantonese? Ask V. S. Subrahmanian of the University of Maryland, who created an algorithm that mines online social networks like Facebook. Or maybe you want an entrée into a terrorist network? Dutch researchers defined the mathematical signatures of likely terrorists within large, online social networks, and Subrahmanian now knows how to find them.

If you want a smart third arm for diapering or dueling or gourmet cooking, MacArthur genius and University of Washington biorobotics expert Yoky Matsuoka can attach one directly to your brain.

“We go anywhere from skin contact to something that goes on the surface of muscles to brain surface interface to opening up the skull, peeling off the skin, and sticking needles into the brain itself,” Matsuoka says.

That’s very cool: Robotic prosthetics can now attach directly to and be controlled by neurons. If you’re down an arm, you can strap a replacement to the neurons that would naturally control the missing limb. Or if you’re still in possession of a full set and just looking for that “wow” factor, you can hook a prosthetic to a random, excitable neuron and train the neuron to control the arm. Check out online footage of monkeys at the University of Pittsburgh MotorLab: after using a brain-connected prosthesis to eat an apple, one monkey brings the hand close so he can lick his “fingers.”

The question is, how much autonomy do you allow in your third arm? “We’re going to have to warm up to the idea of letting the robot do more,” says Matsuoka. That’s because brain control is still a bit crude. And so instead of an arm that you instruct to pick up a Stratocaster and push each fret at exactly the right millisecond, it’s easier to leave some “smartness” or degree of control in the prosthetic: Your brain may initiate “play guitar solo from Danish glam band White Lion’s ‘When the Children Cry,’ ” but then it’s simpler to let the limb do it independently than it is to leave your brain in control.

Is that a bad thing? OK, in the preceding example it probably is—with or without a third arm, there’s no excuse for wanting to play the guitar solo from “When the Children Cry.” But in terms of robotic autonomy versus human control, ceding volition to robot overlords isn’t a new thing. We already allow robot autonomy in devices like dishwashers, garage door openers, and Little League pitching machines—once we give the command, they automatically do the work. Would it be so wrong or even so different to “hijack a couple neurons,” as Matsuoka puts it, and attach these machines to our brains rather than pushing buttons with our hands?

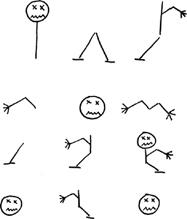

Puzzle #7:

Dismembered Zombies

Oh no! The zombies below have become inconveniently dismembered! But even a zombie missing one limb is viable. How can you combine the pieces below to create the most viable zombies? Assume right and left limbs are not interchangeable, you can’t double up limbs, bodies, or heads, and you have no access to a chainsaw, axe, or other tool of further dismemberment.

“Here’s the story of the only truly awesome play I’ve ever made,” says understated Jason Katz-Brown, former US #1-ranked Scrabble player, and cocreator with John O’Laughlin of the gold-standard Scrabble site Quackle (

www.quackle.org

). “There were two tiles left in the bag and I was down by, like, a hundred points, holding E-G-I-N-S-Y-Blank.” There are a lot of bingos he could’ve played from this bunch—words

that use all seven tiles and thus score an additional fifty bonus points. “But it wouldn’t have mattered,” he says, “because next turn my opponent could’ve scored more points,” and Katz-Brown would’ve been stuck playing catch-up again, with only the two tiles he drew from the bag as ammunition. He computed or intuited the odds—exactly which, he’s not sure—and realized that his best play was to pass and ditch his E in hope of getting a higher-value letter that would allow him to bingo out. He drew a P, for G-I-N-P-S-Y-Blank. His opponent played and drew the only remaining tile, a J. Playing off a G on the board, Katz-Brown bingoed out with “gypsying,” which my spell check doesn’t like, but which is most certainly included in the

Official Scrabble Players Dictionary

. Not only did he bingo out big, but his opponent had to eat the J, swinging the score by another sixteen points. “I won by, like, a few points,” says Katz-Brown. Lucky as it may seem, the thing is he foresaw this as his only chance.

I’m a casual Scrabble player, usually on my phone in bed at night, and I reciprocated with the very exciting story of my best play—the word “prejudice” off an existing “re” while playing against the computer a couple months ago. Katz-Brown was kind enough to pretend to be impressed.

This is to say that there are many levels at which Scrabble can be played. But according to Katz-Brown, the two basic tenets of good play are as applicable to me as they are to him: (1) know your words; and (2) be aware of the likely value of letters you leave in your rack. This is how Quackle computes word score—points plus leave value—and Katz-Brown says that when he sets Quackle to play only according to these two parameters, it can beat all but the best human players.

First, the words. After his freshman year at MIT, Katz-Brown took a summer internship in Japan (where he now works for Google). “And instead of taking advantage of, you know, Japan,” he says, “I’d go back to my room and spend all night learning

words.” That summer, he learned all the words in

The Official Scrabble Players Dictionary

.

Let’s imagine you’re not going to do the same. Is there a way to get better at Scrabble with minutes—rather than months—of memorization? If you only wanted to spend time learning a handful of words, which should they be?

To find out, Katz-Brown and O’Laughlin had Quackle play itself thousands of times and looked for the best words. But these aren’t simply the highest-scoring words; rather, they’re the ones that allow the most advantage over other words you’d play with the same rack if you didn’t know the big kahuna. For example, with an opening rack of E-H-O-P-Q-R-T, the best word is “qoph” (valued by Quackle at 46.6) and the second best word is “thorpe” (at 24.8). There’s a big difference for knowing “qoph,” and so it has high “playability.”

In order of playability, the top forty words you absolutely must know are: qi, qat, xi, ox, za, ex, qis, ax, zo, jo, ja, xu, qadi, qaid, of, oo, if, oe, io, qua, yo, oi, euoi, oy, ow, wo, yu, fy, ee, joe, aw, we, zee, oxo, exo, axe, ye, fa, ou, ef. The first bingo on the list is “etaerio.” You can find the full list with a quick search for “O’Laughlin playability.”

Now to leave values, which are a bit more esoteric. Sure, it’s nice to score points. But it’s also nice to set yourself up to score points next time. This is what you do when you play tiles that leave compatible letters in your rack. Again, Katz-Brown and O’Laughlin engineered massive Quackle-on-Quackle action to discover the combinations that predict success on the next turn. If you’re going to keep only one tile, best keep the blank (notated “?”), followed by S, Z, X, R, and H. Many of the same suspects show up in two-tile leaves, with the best being ?-?, ?-S, ?-R, ?-Z and the first without a blank being S-Z. If you’re leaving three tiles, none of them blank, oh please let them be E-R-S! Other great three-tile leaves are E-S-T, E-S-Z, R-S-T, and E-R-Z. And it’s likely worth ditching one letter if you can leave A-C-E-H-R-S, E-I-P-R-S-T, or E-G-I-N-R-S. You can find full lists by searching for “O’Laughlin maximal leaves.”

To demonstrate the power of leave values, Katz-Brown suggests imagining an opening rack of A-E-P-P-Q-R-S. “There’s no bingo, and there’s no obviously exciting play that scores a lot,” he says. So what should you do? Despite Q’s high points and what Katz-Brown describes as most players’ “animal fear of having two of the same letter in your rack,” the best play is to exchange the Q. With A-E-P-P-R-S, drawing any vowel will allow you to bingo next turn.

Data generation to solve specific questions? While Katz-Brown is the only person in this book without a PhD, knowledge creation through experimentation sounds suspiciously like science to me. There you have it: Scrabble solved with science.

“I can only define the two-letter words,” says

Katz-Brown, which puts him two letters ahead of most players in the world’s top Scrabble country, Thailand, where players generally memorize acceptable and unacceptable letter patterns without connecting these patterns to words or meanings. At the yearly bigwig tournament in Thailand, Katz-Brown describes being mobbed by groupies for pictures and autographs. This, he implies, is somewhat different than the way top Scrabble players are treated in the United States.

Puzzle #8:

Bingo! (Scrabble)

What five bingos can you make with the letters E-A-S-T-E-R-L?