Brain Trust (30 page)

Authors: Garth Sundem

Earning a world record allows paper plane designers to own football teams and date Russian oil heiresses. And according to aerospace engineer Ken Blackburn, current record holder and author of

The World Record Paper Airplane Book

, you need master only three things in your quest for paper plane glory: good folds, good throw, and good design.

Let’s polish off the first two in a couple words: Good folds are extremely crisp, reducing the plane’s profile and thus its drag. They also make the plane perfectly symmetrical. And a good throw means different things for different planes (we’ll get into specs later), but for a world-record attempt, you use a baseball-style throw to launch the plane straight up, as high as possible—there’s video of Blackburn’s Georgia Dome launch and subsequent 27.6-second, world-record flight online at

www.paperplane.org

.

Now to design, wherein lies the true geekery of paper planes.

“Long, rectangular wings are for slow speeds and long glides, and short, swept-back wings are for high speeds and maneuverability,” says Blackburn. You can see this in the difference between the condor and the swallow. The first is optimized for slow soaring, while the second—assuming an unladen European swallow—is optimized for quick dips and dives. You can also see these swept-back wings on the Space Shuttle, and because these high-speed wings have very little lift at low speeds, the Shuttle needs to keep an aggressive, nose-up angle of attack even when landing. A straight-winged Cessna can land almost flat to the runway.

These triangular wings certainly have a paper plane design purpose. “I make pointed airplanes myself,” says Blackburn. “They certainly look cooler, and if you’re just throwing a paper plane

across the room, you might as well have something that looks cool.”

But a world-record plane needs both the ability to act like a dart during launch, and like a glider after it levels off—a tricky balance. “People don’t realize how desperately I would love to fold my plane the long way,” says Blackburn, which would allow him to make wings from the 11-inch rather than 8.5-inch side of the paper. But so far he’s been unable to find a design that has both long wings and the ability to withstand the force of the nearly 60 mph launching throw.

Wing shape defines other aspects of design too.

“For a rectangular, or nearly rectangular wing, the center of gravity should be a quarter of the distance from tip to tail,” says Blackburn, “but for a plane with triangular wings, the center of gravity should be right at the midpoint.” Basically, this is because the additional lift of a rectangular wing requires additional weight up front to keep the plane from pulling immediately nose-up and flipping instead of flying. “The further forward your center of gravity, the more your plane acts like a weather vane,” says Blackburn. But you don’t want to hang an anvil off the nose—that would negate the effect of lift. So optimal design is a balance between stability and lift.

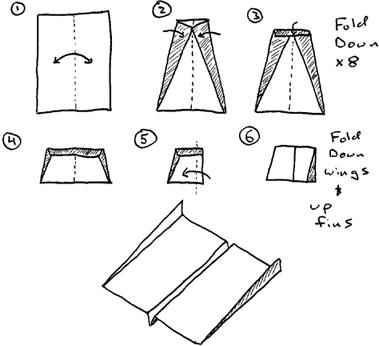

Mathematically, it means that in a square-winged plane, you need exactly half the plane’s weight right up front on the nose to make the full center of gravity rest a quarter of the way back. In the supersimple airplane below, it’s easy to see that you want to fold exactly half the paper into the plane’s leading edge.

Recreationally, you can adjust your paper plane’s center of gravity with a paperclip. A cheater clip also helps ensure your plane’s center of gravity remains below the wing, on the fuselage, making your plane stable right side up. But world-record rules disallow any additions to the paper and so creative folding is required.

Instead of adding aerodynamically beneficial ballast, fold your wings slightly up, so that when you look directly at the plane’s nose, the fuselage and wings form the letter “Y,” not the letter “T” (horizontal wings) and certainly not like an upward-pointing arrow or three-line Christmas tree (downward angled wings).

Blackburn also gently folds up the wing’s trailing edge to make his launchable dart a little more like a glider once it levels off. Flaps-up means that air pushes down on the trailing edge, slightly rotating the plane around its center of gravity and keeping the nose up. Like the Space Shuttle, which is forced to land with its nose high in the air, an increased angle of attack creates increased lift (as long as it doesn’t make the plane flip).

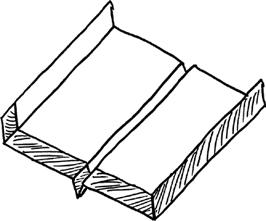

Notice all these design features in the plans for Blackburn’s world-record paper airplane, shown below. But also notice that there might be room for improvement—can you lengthen the wings while still allowing a dartlike launch? If so, the paper plane world record and all its glory could be yours.

* From

The World Record Paper Airplane Book

, by Ken Blackburn

There are two kinds of people in this world: slackers and achievers. Achievers know how to spot slackers—they’re the ones lounging by the lockers, collars turned up, sporting multiply pierced ears and asymmetrical smiles, listening to that new-fangled rock and roll music. And slackers know how to spot

achievers—always on time and uptight, multiple sharpened pencils, taking notes as teachers blather on.

But do you know which one you are? Deceased Harvard researcher David McLelland saw the difference in tossers. He allowed subjects to choose the distance from which they tossed a ring at a post—people motivated by achievement picked a distance at which the task was tricky but not impossible, allowing them to succeed with effort and thus train their skills. People motivated by fun either chose close distances at which they could succeed every time, or impossibly far distances that required an entertaining, lucky throw to succeed. Do you push yourself at the gym (trying to lift ever heavier weights) or with your morning paper (you time the crossword)? If so, you’re motivated by achievement rather than enjoyment.

OK, OK, social psychologist Dolores Albarracin of the University of Illinois points out that the difference isn’t that stark—whether you’re motivated by enjoyment or by achievement sits on a continuum, allowing you to hold both within you—maybe you have “6” motivation for fun and “8” motivation for achievement. But people sitting at different spots on that continuum are measurably different.

Albarracin showed this by testing fun/achievement motivation and then priming people with achievement words like

strive, attain, win, master

, and

compete

. Thus primed, achievers became even more motivated to achieve. But people naturally motivated by enjoyment rebelled against the priming and became even more motivated by fun.

In a follow-up, Albarracin showed that not only did this priming change attitudes, but it also changed behaviors. After again testing fun/achievement motivation and again priming subjects with achievement words, Albarracin plugged subjects into a word search task that she said was meant to measure verbal ability. Then

the task was interrupted—blamed on computer problems—and after a couple minutes, subjects were given the choice to resume the word search task (achievement) or to switch to a cartoon rating task (fun). Primed achievers were more likely than unprimed achievers to go back to the word search. And fun-seekers primed with achievement words blew off the word search, defecting in droves to the cartoon task.

So making a fun-motivated person aware of an achievement context makes this person do even worse than he would naturally do. You can’t push a slacker to succeed.

The reverse is true too: “If you frame a task as fun, achievers do worse,” says Albarracin, “which is really depressing.”

The implications are obvious: If you want fun-motivated students or workers (slackers!) to achieve, frame an activity as “so much fun!” rather than in the language of winning, losing, and striving. Likewise, if you know that you’re one of these slackers and have a big project coming up, find a way to think of it as fun. If the task is simply horrible enough to preclude masking it with fun, Albarracin suggests using a “get your work done so you can play” mind-set. This allows fun to remain the goal, while ensuring slackers get their work done too.

Right now it’s a beautiful, crisp fall day and I’d really like to wander downtown and pick up a used book and an ice-cream cone. Just five hundred more words and I’m out the door.

Albarracin found that the more a person

believes they can defend an opinion from attack, the more likely the person is to change this same opinion in the face of contradictory evidence. Albarracin thinks it’s likely that people with high “defensive confidence” have amassed these internal arguments as walls around a position they realize is weak.

Remember Finkel and Eastwick and their recommendations for speed dating success? Well, now they’re all up in the grill of smooth operating. What, specifically, makes an initial romantic encounter smooth and what makes it awkward?

To answer the question, they and their colleague Seema Saigal gathered four-minute tapes of (independently rated) smooth and awkward first conversations between romantically inclined Northwestern University undergrads and then coded the behaviors they saw. As you’d expect, dates who exuded warmth and who were more focused on their dates than they were on themselves tended to create smoother conversations.