Read Chicken Soup for the Canadian Soul Online

Authors: Jack Canfield

Chicken Soup for the Canadian Soul (27 page)

Deep in despair, I sat typing up resumes and cover letters for Doug. Out of the corner of my eye I could see our thirteen-month-old son, Forrest, as he lay on the carpet, playing near our big, gentle nanny-dog, Brigitte. I hadn’t typed more than two sentences when our other dog, Bambi, began barking furiously and running back and forth to the sliding glass door overlooking our pool.

I raced to see what was happening and noticed that the sliding door was slightly open. Suddenly, I realized Forrest was nowhere to be seen. In a panic, I opened the door and ran outside. There I was surprised to see Brigitte, who was terrified of water, splashing around in the pool. Then to my horror, my eyes caught sight of Forrest’s yellow sleeper. Brigitte was bravely doing her best to keep him afloat by holding on to his sleeper with her mouth. At the same time, she was desperately trying to swim to the shallow end. I realized that Forrest had somehow opened the door, wandered out and fallen into the pool.

In a split second, I dove in, lifted my precious baby out and carried him inside. But when I realized Forrest wasn’t breathing, I began to go into shock. I was trained in CPR, but my mind went completely blank. When I called 911, all I could do was scream. On the other end, a paramedic tried to calm me down so that I could follow his CPR instructions, but in my hysteria I was unable to carry it out successfully. Thankfully, Doug, who was a former Canadian Forces officer and was trained in CPR, arrived and took over. I stood by with my heart in my throat, and after about three minutes, Forrest began to breathe again.

When the ambulance arrived, I rode with Forrest to the hospital. Along the way he stopped breathing a couple of times, but each time the paramedics managed to revive him.

Once at the hospital, it wasn’t long before a doctor told us that Forrest would be all right. Doug and I were overwhelmed with gratitude. They kept him for observation for a total of four days, and I stayed by his side the whole time.

While Forrest was in the hospital, Doug was often at home. When he went into Forrest’s bedroom, he discovered that both Brigitte and Bambi had crammed themselves under the crib. For the entire time that Forrest was in the hospital, they ate little, coming out only to drink water. Otherwise, they remained under the crib, keeping a vigil until we brought Forrest home. Once they saw he was back, Brigitte and Bambi began to bark with apparent joy and wouldn’t let Forrest out of their sight. Our two wonderful dogs remained concerned about our baby’s safety, and even my first attempts to bathe Forrest were traumatic. Brigitte and Bambi stood watch, whimpering the whole time.

In time they settled down, but both remained dedicated to Forrest and followed him everywhere. When Forrest finally learned to walk, he did it by holding on to the dogs’ collars.

The press discovered the story and soon Purina dog food called. They offered the dogs an award and gave us tickets to fly to Toronto for a ceremony where Brigitte and Bambi were awarded medals for their bravery. We were also given a beautiful framed picture of our dogs, which we now display proudly above our mantle. Perhaps best of all, Purina gave us a lifetime supply of dog food so the problem of keeping our beloved dogs was solved.

Those gentle giants helped raise our other two children as well. Things in our lives are much better now. Most importantly, almost losing Forrest—and then getting him back—erased any despair I might have had about losing our home. A house can always be replaced, but knowing we have each other is the greatest blessing of all.

Our two dogs are both angels now and probably guarding other children up in heaven. We miss them both, but we are eternally grateful they were part of our lives.

Karin Bjerke-Lisle

White Rock, British Columbia

Before my dad died, Christmas was a bright, enchanted time in the long, dark winters of Bathurst, New Brunswick. The cold, blizzardy days would sometimes start as early as late September. Finally, the lights of Christmas would start to go up, and the anticipation would build. By Christmas Eve the ordinary evergreen tree that my father dragged in the door ten days earlier took on a magical, sparkling life of its own. With its marvellous brilliance, it single-handedly pushed back the darkness of winter.

Late on Christmas Eve, we would bundle up and go to midnight mass. The sound of the choir sent chills through my body, and when my older sister, a soloist, sang “Silent Night,” my cheeks flushed with pride.

On Christmas morning I was always the first one up. I’d stumble out of bed and walk down the hall toward the glow from the living room. My eyes filled with sleep, I’d softly bounce off the walls a couple of times trying to keep a straight line. I’d round the corner and come face-to-face with the brilliance of Christmas. My unfocused, sleep-filled eyes created a halo around each light, amplifying and warming it. After a moment or two I’d rub my eyes and an endless expanse of ribbons and bows and a free-for-all of bright presents would come into focus.

I’ll never forget the feeling of that first glimpse on Christmas morning. After a few minutes alone with the magic, I’d get my younger brother and sister, and we’d wake my parents.

One November night, about a month before Christmas, I was sitting at the dining room table playing solitaire. My mother was busy in the kitchen, but was drawn from time to time into the living room by one of her favourite radio shows. It was dark and cold outside, but warm inside. My father had promised that tonight we would play crazy eight’s, but he had not yet returned from work and it was getting near my bedtime.

When I heard him at the kitchen door, I jumped up and brushed past my mother to meet him. He looked oddly preoccupied, staring past me at my mother. Still, when I ran up to him, he enfolded me in his arms. Hugging my father on a winter night was great. His cold winter coat pressed against my cheek and the smell of frost mingled with the smell of wool.

But this time was different. After the first few seconds of the familiar hug, his grip tightened. One arm pressed my shoulder while the hand on my head gripped my hair so tightly it was starting to hurt. I was a little frightened at the strangeness of this and relieved when my mother pried me out of his arms. I didn’t know it at the time, but my dad was suffering a fatal heart attack.

Someone told me to take my younger brother and sister to play down in the recreation room. From the foot of the stairs, I saw the doctor and the priest arrive. I saw an ambulance crew enter and then leave with someone on a stretcher, covered in a red blanket. I didn’t cry the night my father died, or even at his funeral. I wasn’t holding back the tears; they just weren’t there.

On Christmas morning, as usual, I was the first one up. But this year, something was different. Already, there was a hint of dawn in the sky. More rested and awake than usual, I walked down the hall toward the living room. There was definitely something wrong, but I didn’t know what until I rounded the corner. Then, instead of being blinded by the warm lights, I could see everything in the dull room. Without my dad to make sure the lights on the tree were glowing, I could see the tree. I could see the presents. I could even see a little bit of the outside world through the window. The magic of my childhood Christmas dream was shattered.

The years passed. As a young man, I always volunteered to work the Christmas shifts. Christmas Day wasn’t good, it wasn’t bad; it was just another grey day in winter, and I could always get great overtime pay for working.

Eventually, I fell in love and married, and our son’s first Christmas was the best one I’d had in twenty years. As he got older, Christmas got even better. By the time his sister arrived, we had a few family traditions of our own. With two kids, Christmas became a great time of year. It was fun getting ready for it, fun watching the children’s excitement and most especially, fun spending Christmas day with my family.

On Christmas Eve I continued the tradition started by my dad and left the tree lights on for that one night, so that in the morning, my kids could have that wonderful experience.

When my son was nine years old, the same age I was when my father died, I fell asleep Christmas Eve in the recliner watching midnight mass on TV. The choir was singing beautifully, and the last thing I remember was wishing to hear my sister sing “Silent Night” again. I awoke in the early morning to the sound of my son bouncing off the walls as he came down the hallway toward the living room. He stopped and stared at the tree, his jaw slack.

Seeing him like that reminded me of myself so many years ago, and I knew. I knew how much my father must have loved me in exactly the same complete way I loved my son. I knew he had felt the same mixture of pride, joy and limitless love for me. And in that moment, I knew how angry I had been with my father for dying, and I knew how much love I had withheld throughout my life because of that anger.

In every way I felt like a little boy. Tears threatened to spill out and no words could express my immense sorrow and irrepressible joy. I rubbed my eyes with the back of my hands to clear them. Eyes moist and vision blurred, I looked at my son, who was now standing by the tree. Oh my, the glorious tree! It was the Christmas tree of my childhood!

Through my tears the tree lights radiated a brilliant, warm glow. Soft, shimmering yellows, greens, reds and blues enveloped my son and me. My father’s death had stolen the lights and life out of Christmas. By loving my own son as much as my father had loved me, I could once more see the lights of Christmas. From that day forward, all the magic and joy of Christmas was mine again.

Michael Hogan

Victoria, British Columbia

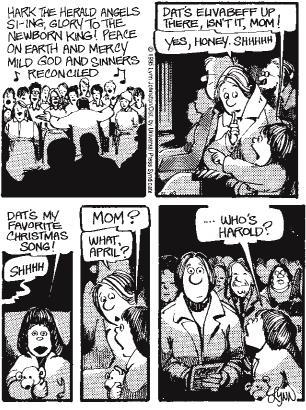

For Better or For Worse

®

by Lynn Johnston

FOR BETTER OR FOR WORSE.

©United Feature Syndicate. Reprinted by permission.

A

nd as we look toward the dawn,

our spirit rises high on wings of certainty.

We will share eternity.

This is how it’s meant to be—

For life goes on, and we must be strong.

Bob Quinn

. . .

W

eeping may remain for a night, but

rejoicing comes in the morning.

Psalm 30:5

The day started out normally enough. It was May 1, 1997. Ryan was upstairs preparing to leave for school, while his six-year-old sister, Jamie, waited for him at the front door. Suddenly Ryan started to tell us all about Albert Einstein with such enthusiasm and excitement, it was as if a light had gone on in this head. He said, “

E=mc

2

—I understand what Einstein was saying: the theory of relativity. I understand now!”

I said, “That’s wonderful,” but thought,

How odd.

It wasn’t his thinking about Einstein—Ryan was so intelligent—but rather the timing that seemed peculiar.

At ten years old, Ryan loved knowledge and seemed to have an abundance of it, far beyond his years. The possibilities of the universe were boundless to him. When he was in first grade, the children in his class were asked to draw a picture and answer the question, “If you could be anyone, who would you be?” Ryan wrote: “If I could be anyone, I’d want to be God.” At age seven, while sitting in church one day, he wrote:

The tree of Life, O, the tree of Glory,

The tree of God of the World, O, the tree of me.

Somehow I think Ryan just “got it.”

In the midst of his strange outburst about Einstein, Ryan suddenly called out that he had a headache. I went upstairs and found him lying on his bed. He looked at me and said, “Oh, Mommy, my head hurts so bad. I don’t know what’s happening to me. You’ve got to get me to the hospital.”