Complete Works (195 page)

S

OCRATES

: So it is not by some kind of wisdom, or by being wise, that such men lead their cities, those such as Themistocles and those mentioned by Anytus just now? That is the reason why they cannot make others be like themselves, because it is not knowledge which makes them what they are.

M

ENO

: It is likely to be as you say, Socrates.

S

OCRATES

: Therefore, if it is not through knowledge, the only alternative is that it is through right opinion that statesmen follow the right course for their cities. As regards knowledge, they are no different from soothsayers [c] for their cities. As regards knowledge, they are no different from soothsayers and prophets. They too say many true things when inspired, but they have no knowledge of what they are saying.—That is probably so.

S

OCRATES

: And so, Meno, is it right to call divine these men who, without any understanding, are right in much that is of importance in what they say and do?—Certainly.

S

OCRATES

: We should be right to call divine also those soothsayers and prophets whom we just mentioned, and all the poets, and we should call [d] no less divine and inspired those public men who are no less under the gods’ influence and possession, as their speeches lead to success in many important matters, though they have no knowledge of what they are saying.—Quite so.

S

OCRATES

: Women too, Meno, call good men divine, and the Spartans, when they eulogize someone, say “This man is divine.”

M

ENO

: And they appear to be right, Socrates, though perhaps Anytus [e] here will be annoyed with you for saying so.

S

OCRATES

: I do not mind that; we shall talk to him again, but if we were right in the way in which we spoke and investigated in this whole discussion, virtue would be neither an inborn quality nor taught, but comes to those who possess it as a gift from the gods which is not accompanied by understanding, unless there is someone among our statesmen who can

[100]

make another into a statesman. If there were one, he could be said to be among the living as Homer said Tiresias was among the dead, namely, that “he alone retained his wits while the others flitted about like shadows.”

19

In the same manner such a man would, as far as virtue is concerned, here also be the only true reality compared, as it were, with shadows.

M

ENO

: I think that is an excellent way to put it, Socrates. [b]

S

OCRATES

: It follows from this reasoning, Meno, that virtue appears to be present in those of us who may possess it as a gift from the gods. We shall have clear knowledge of this when, before we investigate how it comes to be present in men, we first try to find out what virtue in itself is. But now the time has come for me to go. You convince your guest friend Anytus here of these very things of which you have yourself been convinced, in order that he may be more amenable. If you succeed, you will also confer a benefit upon the Athenians.

1

. Prodicus was a well-known sophist who was especially keen on the exact meaning of words.

2

. Empedocles (c. 493–433

B.C.

) of Acragas in Sicily was a philosopher famous for his theories about the world of nature and natural phenomena (including sense-perception).

3

. Frg. 105 (Snell).

4

. Frg. 133 (Snell).

5

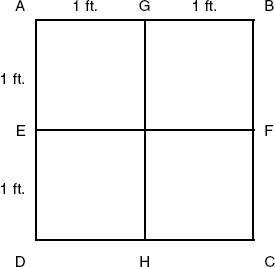

. Socrates draws a square ABCD. The “lines through the middle” are the lines joining the middle of these sides, which also go through the center of the square, namely EF and GH.

6

. I.e., the eight-foot square is double the four-foot square and half the sixteen-foot square—double the square based on a line two feet long, and half the square based on a four-foot side.

7

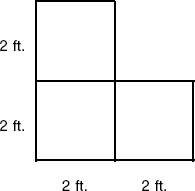

. Socrates now builds up his sixteen-foot square by joining two four-foot squares, then a third, like this:

Filling “the space in the corner” will give another four-foot square, which completes the sixteen-foot square containing four four-foot squares.

8

. “This one” is any one of the inside squares of four feet.

9

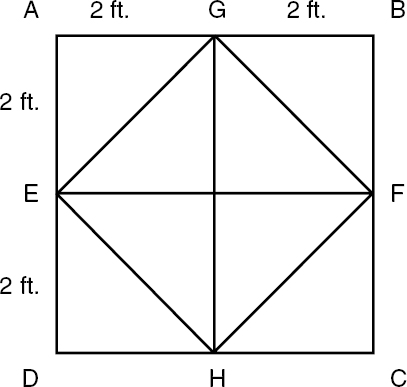

. Socrates now draws the diagonals of the four inside squares, namely, FH, HE, EG, and GF, which together form the square GFHE.

10

. I.e., GFHE.

11

. Again, GFHE: Socrates is asking how many of the triangles “cut off from inside” there are inside GFHE.

12

. I.e., any of the interior squares.

13

. GFHE again.

14

. The translation here follows the interpretation of T. L. Heath,

A History of Greek Mathematics

(Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1921), vol. I, pp. 298 ff.

15

. Anytus was one of Socrates’ accusers at his trial. See

Apology

23e.

16

. Famous Athenian statesman and general of the early fifth century, a leader in the victorious war against the Persians.

17

. Not the historian but Thucydides the son of Melesias, an Athenian statesman who was an opponent of Pericles and who was ostracized in 440

B.C.

18

. Theognis was a poet of the mid-sixth century

B.C.

The quotations below are of lines 33–36 and 434–38 (Diehl) of his elegies.

19

.

Odyssey

x.494–95.

Translated by Paul Woodruff.

This dialogue presents a conversation apparently held in private between Socrates and the sophist Hippias—no company of bystanders is indicated, as they are in

Protagoras

and all Socrates’ other confrontations with those itinerant educators, the sophists. There is another, shorter dialogue also called

Hippias

—whence this one gets the addition

Greater

. Near the beginning of our dialogue, Hippias invites Socrates to come the next day but one to hear and admire him giving an exhibition speech—the very one which gives the occasion for his and Socrates’ discussion in the

Lesser Hippias

. On that later occasion Socrates is plainly not impressed with what he has heard—he stands pointedly silent while the others give it their praises. But here in

Greater Hippias

the invitation reminds him that he has often before praised some parts of other speeches as fine, criticized others as poor, but could never, when challenged, say satisfactorily what it

is

that makes something fine in the first place—as he ought to have done, if he was entitled to issue those judgments. He wishes to make up this deficiency now, by hearing from the wise Hippias (a self-professed know-everything) ‘what the fine is itself’. The Greek word here translated ‘fine’ is

kalon,

a widely applicable term of highly favorable evaluation, covering our ‘beautiful’ (in physical, aesthetic, and moral senses), ‘noble,’ ‘admirable’, ‘excellent’, and the like—it is the same term translated ‘beautiful’ in Diotima’s speech about love and its object in

Symposium

. What Socrates is asking for, then, is a general explanation of what feature any object, or action, or person, or accomplishment of any kind, has to have in order correctly to be characterized as highly valued or worth valuing in this broad way. Hippias, of course, fails to deliver himself of an answer that stands up to scrutiny in discussion with Socrates: Socrates now sees clearly that he does not know what the ‘fine’ is—accordingly, he ought to refrain from issuing judgments about which speeches, or parts of speeches, are fine or the reverse. As a result we have an explanation for Socrates’ unexplained silence at the beginning of

Lesser Hippias

: not knowing what the ‘fine’ itself is, he cannot legitimately evaluate some parts of Hippias’ exhibition as ‘fine’ and others as ‘foul’ and must simply hold his peace—thinking, perhaps, but not saying, that it is no good at all.

Hippias himself offers in succession three definitions of the ‘fine’. Then, following up on things Hippias has said, Socrates initiates a line of questioning that leads to three or four other suggestions. His procedures here, and the objections he finds against the various answers canvassed, should be compared closely with his similar search for definitions in

Euthyphro, Charmides, Laches,

and others of Plato’s ‘Socratic’ dialogues.

The Platonic authenticity of this dialogue has been both attacked and defended by scholars since the beginning of modern scholarship in the early nineteenth century. It is not cited by Aristotle, though in a few passages he may perhaps be referring to things that Socrates says in it. The neat—perhaps too neat—way it connects itself with

Lesser Hippias

might be thought to have its best explanation in an imitator’s exploitation of an opening left by Plato in

Lesser Hippias

for a further

Hippias

dialogue. But its philosophical content seems genuinely Platonic, and scholars have studied it respectfully in exploring the development of Plato’s own theory of Forms out of reflection on Socrates’ search for definitions of moral and other evaluative terms.

J.M.C.

S

OCRATES

: Here comes Hippias, fine and wise! How long it’s been since

[281]

you put in to Athens!

H

IPPIAS

: No spare time, Socrates. Whenever Elis

1

has business to work out with another city, they always come first to me when they choose an ambassador. They think I’m the citizen best able to judge and report [b] messages from the various cities. I’ve often been on missions to other cities, but most often and on the most and greatest affairs to Sparta. That, to answer your question, is why I don’t exactly haunt these parts.

S

OCRATES

: That is what it is like to be truly wise, Hippias, a man of complete accomplishments: in private you are able to make a lot of money from young people (and to give still greater benefits to those from whom you take it); while in public you are able to provide your own city with [c] good service (as is proper for one who expects not to be despised, but admired by ordinary people).

But Hippias, how in the world do you explain this: in the old days people who are still famous for wisdom—Pittacus and Bias and the school of Thales of Miletus, and later ones down to Anaxagoras—that all or most of those people, we see, kept away from affairs of state?

2

H

IPPIAS

: What do you think, Socrates? Isn’t it that they were weak and [d] unable to carry their good sense successfully into both areas, the public and the private?

S

OCRATES

: Then it’s really like the improvements in other skills, isn’t it, where early craftsmen are worthless compared to modern ones? Should we say that your skill—the skill of the sophists—has been improved in the same way, and that the ancients are worthless compared to you in wisdom?

H

IPPIAS

: Yes, certainly, you’re right.

S

OCRATES

: So if Bias came to life again in our time, Hippias, he would

[282]

make himself a laughingstock compared with you people, just as Daedalus

3

also, according to the sculptors, would be laughable if he turned up now doing things like the ones that made him famous.