Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 (2 page)

Read Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

The wider the gaze, the more details of this operation unfold. Like the backdrop of a medieval painting, a fleet of oared ships can be seen moving with laborious sloth against the wind, from the direction of the Dardanelles. High-sided transports are setting sail from the Black Sea with cargoes of wood, grain and cannon balls. From Anatolia, bands of shepherds, holy men, camp followers and vagabonds are slipping down to the Bosphorus out of the plateau, obeying the Ottoman call to arms. This ragged pattern of men and equipment constitutes the co-ordinated movement of an army with a single objective: Constantinople, capital of what little remains in 1453 of the ancient empire of Byzantium.

The medieval peoples about to engage in this struggle were intensely superstitious. They believed in prophecy and looked for omens. Within Constantinople, the ancient monuments and statues were sources of magic. People saw there the future of the world encrypted in the narratives on Roman columns whose original stories had been lost. They read signs in the weather and found the spring of 1453 unsettling. It was unusually wet and cold. Banks of fog hung thickly over the Bosphorus in March. There were earth tremors and unseasonal snow. Within a city taut with expectation it was an ill omen, perhaps even a portent of the world’s end.

The approaching Ottomans also had their superstitions. The object of their offensive was known quite simply as the Red Apple, a symbol of world power. Its capture represented an ardent Islamic desire that stretched back 800 years, almost to the Prophet himself, and it was hedged about with legend, predictions and apocryphal sayings. In the imagination of the advancing army, the apple had a specific location within the city. Outside the mother church of St Sophia on a column 100 feet high stood a huge equestrian statue of the Emperor Justinian in bronze, a monument to the might of the early Byzantine Empire and a symbol of its role as a Christian bulwark against the East. According to the sixth century writer Procopius, it was astonishing.

The horse faces East and is a noble sight. On this horse is a huge statue of the Emperor, dressed like Achilles … his breastplate is in the heroic style; while the helmet covering his head seems to move up and down and it gleams dazzlingly. He looks towards the rising sun, riding, it seems to me towards the Persians. In his left

hand he carries a globe, the sculptor signifying by this that all earth and sea are subject to him, though he has neither sword nor spear nor other weapon, except that on the globe stands the cross through which alone he has achieved his kingdom and his mastery of war.The statue of Justinian

It was in the globe of Justinian surmounted by a cross that the Turks had precisely located the Red Apple and it was this they were coming for: the reputation of the fabulously old Christian empire and the possibility of world power that it seemed to contain.

Fear of siege was etched deep in the memory of the Byzantines. It was the bogeyman that haunted their libraries, their marble chambers and their mosaic churches, but they knew it too well to be surprised. In the 1,123 years up to the spring of 1453 the city had been besieged some twenty-three times. It had fallen just once – not to the Arabs or the Bulgars but to the Christian knights of the Fourth Crusade in one of the most bizarre episodes in Christian history. The land walls had never been breached, though they had been flattened by earthquake in the fifth century. Otherwise they had held firm, so that when the army

of Sultan Mehmet finally reined up outside the city on 6 April 1453, the defenders had reasonable hopes of survival.

What led up to this moment and what happened next is the subject of this book. It is a tale of human courage and cruelty, of technical ingenuity, luck, cowardice, prejudice and mystery. It also touches on many other aspects of a world on the cusp of change: the development of guns, the art of siege warfare, naval tactics, the religious beliefs, myths and superstitions of medieval people. But above all it is the story of a place – of sea currents, hills, peninsulas and weather – the way the land rises and falls and how the straits divide two continents so narrowly ‘they almost kiss’, where the city is strong, defended by rocky shores, and the particular features of geology that render it vulnerable to attack. It was the possibilities of this site – what it offered for trade, defence and food – that made Constantinople the key to imperial destinies and brought so many armies to its gate. ‘The seat of the Roman Empire is Constantinople’, wrote George Trapezuntios, ‘and he who is and remains Emperor of the Romans is also the Emperor of the whole earth.’

Modern nationalisms have interpreted the siege of Constantinople as a struggle between the Greek and Turkish peoples, but such simplifications are misleading. Neither side would have readily accepted or even understood these labels, though each used them of the other. The Ottomans, literally the tribe of Osman, called themselves just that, or simply Muslims. ‘Turk’ was a largely pejorative term applied by the nation states of the West, the name ‘Turkey’ unknown to them until borrowed from Europe to create the new Republic in 1923. The Ottoman Empire in 1453 was already a multicultural creation that sucked in the peoples it conquered with little concern for ethnic identity. Its crack troops were Slavs, its leading general Greek, its admiral Bulgarian, its sultan probably half Serbian or Macedonian. Furthermore under the complex code of medieval vassalage, thousands of Christian troops accompanied him down the road from Edirne. They had come to conquer the Greek-speaking inhabitants of Constantinople, whom we now call the Byzantines, a word first used in English in 1853, exactly 400 years after the great siege. They were considered to be heirs to the Roman Empire and referred to themselves accordingly as Romans. In turn they were commanded by an emperor who was half Serbian and a quarter Italian, and much of the defence was undertaken

by people from Western Europe whom the Byzantines called ‘Franks’: Venetians, Genoese and Catalans, aided by some ethnic Turks, Cretans – and one Scotsman. If it is difficult to fix simple identities or loyalties to the participants at the siege, there was one dimension of the struggle that all the contemporary chroniclers never forgot – that of faith. The Muslims referred to their adversary as ‘the despicable infidels’, ‘the wretched unbelievers’, ‘the enemies of the Faith’; in response they were called ‘pagans’, ‘heathen infidels’, ‘the faithless Turks’. Constantinople was the front line in a long-distance struggle between Islam and Christianity for the true faith. It was a place where different versions of the truth had confronted each other in war and truce for 800 years and it was here in the spring of 1453 that new and lasting attitudes between the two great monotheisms were to be cemented in one intense moment of history.

Epigraph

‘Constantinople is a city . . .’, quoted Stacton, p. 153

‘I shall tell the story . . .’, Melville Jones, p. 12

Prologue

1

‘The horse faces East . . .’, Procopius, p. 35

2

‘The seat of the Roman . . .’, Mansel, p. 1

629–717

O Christ, ruler and master of the world, to You now I dedicate this subject city, and these sceptres and the might of Rome.

Inscription on the column of Constantine the Great in Constantinople

Islam’s desire for the city is almost as old as Islam itself. The origin of the holy war for Constantinople starts with the Prophet himself in an incident whose literal truth, like so much of the city’s history, cannot be verified.

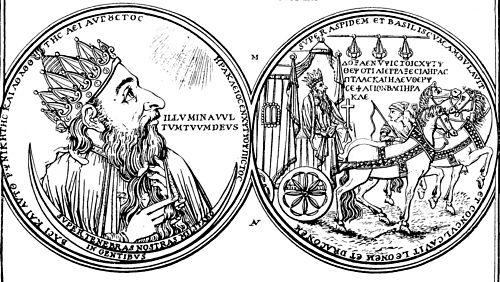

In the year 629, Heraclius, ‘Autocrat of the Romans’ and twenty-eighth Emperor of Byzantium, was making a pilgrimage on foot to Jerusalem. It was the crowning moment of his life. He had shattered the Persians in a series of remarkable victories and wrested back Christendom’s most sacred relic, the True Cross, which he was triumphantly restoring to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. According to Islamic tradition, when he had reached the city he received a letter. It said simply: ‘In the name of Allah the most Beneficent, the most Merciful: this letter is from Muhammad, the slave of Allah, and His Apostle, to Heraclius, the ruler of Byzantines. Peace be upon the followers of guidance. I invite you to surrender to Allah. Embrace Islam and Allah will bestow on you a double reward. But if you reject this invitation you will be misguiding your people.’ Heraclius had no idea who the writer of this letter might have been, but he is reported to have made inquiries and to have treated its contents with some

respect. A similar letter sent to the ‘King of Kings’ in Persia was torn up. Muhammad’s reply to this news was blunt: ‘Tell him that my religion and my sovereignty will reach limits which the kingdom of Chosroes never attained.’ For Chosroes it was too late – he had been slowly shot to death with arrows the year before – but the apocryphal letter foreshadowed an extraordinary blow about to fall on Christian Byzantium and its capital, Constantinople, that would undo all the emperor ever achieved.

Heraclius rides in triumph with the true cross

In the previous ten years Muhammad had succeeded in unifying the feuding tribes of the Arabian Peninsula around the simple message of Islam. Motivated by the word of God and disciplined by communal prayer, bands of nomadic raiders were transformed into an organized fighting force, whose hunger was now projected outwards beyond the desert’s rim into a world sharply divided by faith into two distinct zones. On the one side lay the

Dar al-Islam

, the House of Islam; on the other, the realms still to be converted, the

Dar al-Harb

, the House of War. By the 630s Muslim armies started to appear on the margins of the Byzantine frontier, where the settled land gives way to desert, like ghosts out of a sandstorm. The Arabs were agile, resourceful and hardy. They totally surprised the lumbering mercenary armies in Syria. They attacked then retreated into the desert, lured their opponents out of their strongholds into the barren wilderness, surrounded and massacred them. They traversed the harsh empty quarters, killing their

camels as they went and drinking the water from their stomachs – to emerge again unexpectedly behind their enemy. They besieged cities and learned how to take them. Damascus fell, then Jerusalem itself; Egypt surrendered in 641, Armenia in 653; within twenty years the Persian Empire had collapsed and converted to Islam. The velocity of conquest was staggering, the ability to adapt extraordinary. Driven by the word of God and divine conquest, the people of the desert constructed navies ‘to wage the holy war by sea’ in the dockyards of Egypt and Palestine with the help of native Christians and took Cyprus in 648, then defeated a Byzantine fleet at the Battle of the Masts in 655. Finally in 669, within forty years of Muhammad’s death, the Caliph Muawiyyah dispatched a huge amphibious force to strike a knockout blow at Constantinople itself. On the following wind of victory, he had every anticipation of success.