Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 (4 page)

Read Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Byzantium was not only the last heir to the Roman Empire, it was also the first Christian nation. From its founding, the capital city was conceived as the replica of heaven, a manifestation of the triumph of Christ, and its emperor was considered God’s vice-regent on earth. Christian worship was evident everywhere: in the raised domes of the churches, the tolling of bells and wooden gongs, the monasteries, the huge number of monks and nuns, the endless parade of icons around the streets and walls, the ceaseless round of prayer and Christian ceremony within which the devout citizens and their emperor lived. Fasts, feast days and all-night vigils provided the calendar, the clock and the framework of life. The city became the storehouse of the relics of Christendom, collected from the Holy Land and eyed with envy by Christians in the West. Here they had the head of John the Baptist, the crown of thorns, the nails from the cross and the stone from the tomb,

the relics of the apostles and a thousand other miracle-working artefacts encased in reliquaries of gold and studded with gems. Orthodox religion worked powerfully on the emotions of the people through the intense colours of its mosaics and icons, the mysterious beauty of its liturgy rising and falling in the darkness of lamplit churches, the incense and the elaborate ceremonial that enveloped church and emperor alike in a labyrinth of gorgeous ritual designed to ravish the senses with its metaphors of the heavenly sphere. A Russian visitor who witnessed an imperial coronation in 1391 was astonished by the slow-motion sumptuousness of the event:

during this time, the cantors intoned a most beautiful and astonishing chant, surpassing understanding. The imperial cortège advanced so slowly that it took three hours from the great door to the platform bearing the throne. Twelve men-at-arms, covered with mail from head to foot, surrounded the Emperor. Before him marched two standard-bearers with black hair: the poles of their standards, their costume, and their headdress were red. Before these standard-bearers went heralds: their rods were plated with silver … Ascending the platform, the Emperor put on the imperial purple and the imperial diadem and the crenated crown … Then the holy liturgy began. Who can describe the beauty of it all?

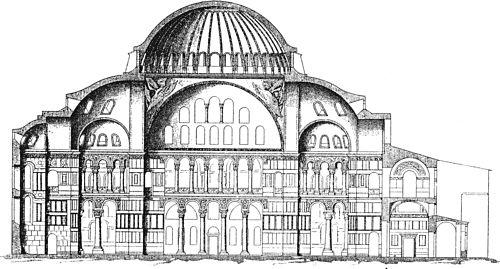

Anchored in the centre of the city, like a mighty ship, was the great church of St Sophia, built by Justinian in only six years and dedicated in 537. It was the most extraordinary building in late antiquity, a structure whose immensity was matched only by its splendour. The huge levitated dome was an incomprehensible miracle to eyewitnesses. ‘It seems’, said Procopius, ‘not to rest upon solid masonry but to cover the space beneath as though suspended from heaven.’ It encased a volume of space so vast that those seeing it for the first time were left literally speechless. The vaulting, decorated with four acres of gold mosaic, was so brilliant, according to Paul the Silentiary, that ‘the golden stream of rays pours down and strikes the eyes of men, so that they can scarcely bear to look’, while its wealth of coloured marbles moved him to poetic trance. They looked as though they were ‘powdered with stars … like milk splashed over a surface of shining black … or like the sea or emerald stone, or again like blue cornflowers in grass, with here and there a drift of snow’. It was the beauty of the liturgy in St Sophia that converted Russia to Orthodoxy after a fact-finding mission from Kiev in the tenth century experienced the service and reported back: ‘We knew not whether we were in Heaven or earth. For on earth there is no such splendour and beauty, and we are

at a loss how to describe it. We only know that there God dwells among men.’ The detailed gorgeousness of Orthodoxy was the reversed image of the sparse purity of Islam. One offered the abstract simplicity of the desert horizon, a portable worship that could be performed anywhere as long as you could see the sun, a direct contact with God, the other images, colours and music, ravishing metaphors of the divine mystery designed to lead the soul to heaven. Both were equally intent on converting the world to their vision of God.

St Sophia in cross-section

The Byzantines lived their spiritual life with an intensity hardly matched in the history of Christendom. The stability of the empire was at times threatened by the number of army officers who retired to monasteries and theological issues were debated on the streets with a passion that led to riots. ‘The city is full of workmen and slaves who are all theologians,’ reported one irritated visitor. ‘If you ask a man to change money he will tell you how the Son differs from the Father. If you ask the price of a loaf he will argue that the Son is less than the Father. If you want to know if the bath is ready you are told that the Son was made out of nothing.’ Was Christ one or many? Was the Holy Spirit descended just from the Father or from the Father and the Son? Were icons idolatrous or holy? These were not idle questions: salvation or damnation hung on the answers. Issues of orthodoxy and heresy were as explosive as civil wars in the life of the empire and they undermined its unity just as effectively.

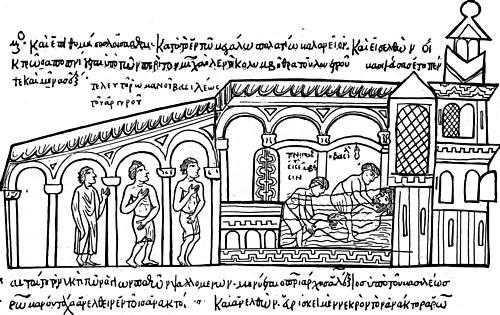

The world of Byzantine Christianity was also strangely fatalistic. Everything was ordained by God, and misfortune on any scale, from the loss of a purse to a major siege, was considered to be the result of personal or collective sin. The emperor was appointed at God’s bidding, but if he were overthrown in a palace coup – hacked to death by plotters or stabbed in his bath or strangled or dragged along behind horses or just blinded and sent into exile (for imperial fortunes were notoriously unstable) – this was God’s will too and betokened some hidden sin. And because fortune was foretold, the Byzantines were superstitiously obsessed with prophecy. It was common for insecure emperors to open and read the Bible at random to get clues to their fate; divination was a major preoccupation, often railed against by the clergy, but too deeply ingrained to be expunged from the Greek soul. It took some bizarre forms. An Arab visitor in the ninth century witnessed a curious use of horses to report on the progress of a distant army campaign: ‘They are introduced into the church where bridles have been suspended. If the horse takes the bridle in its mouth, the people say: “We have gained a victory in the land of Islam.” [Sometimes] the horse approaches, smells at the bridle, comes back and does not draw near any more to the bridle.’ In the latter case, the people presumably departed in gloomy expectation of defeat.

The perils of high office: the Emperor Romanus Augustus Argyrus drowned in his bath, 1034

For long centuries the image of Byzantium and its capital city, brilliant as the sun, exercised a gravitational pull on the world beyond its frontiers. It projected a dazzling image of wealth and longevity. Its currency, the bezant, surmounted by the head of its emperors, was the gold standard of the Middle East. The prestige of the Roman Empire attached to its name; in the Muslim world it was known simply as

Rum

, Rome, and like Rome it attracted the desire and envy of the nomadic semi-barbarous peoples beyond its gates. From the Balkans and the plains of Hungary, from the Russian forests and the Asian steppes turbulent waves of tribal wanderers battered at its defences: the Huns and the Goths, the Slavs and the Gepids, the Tartar Avars, the Turkic Bulgars and the wild Pechenegs all wandered across the Byzantine world.

The empire at its height ringed the Mediterranean from Italy to Tunis, but expanded and contracted continuously under the pressure of these neighbours like an enormous map forever curling at the edges. Year after year imperial armies and fleets departed from the great harbours on the Marmara shore, banners flying and trumpets sounding, to regain a province or secure a frontier. Byzantium was an empire forever at war and Constantinople, because of its position at the crossroads, was repeatedly pressurized from both Europe and Asia. The Arabs were merely the most determined in a long succession of armies camped along the land walls in the first five hundred years of its existence. The Persians and the Avars came in 626, the Bulgars repeatedly in the eighth, ninth, and tenth centuries, Prince Igor the Russian in 941. Siege was a state of mind for the Greek people and their oldest myth: after the Bible, people knew Homer’s tale of Troy. It made them both practical and superstitious. The maintenance of the city walls was a constant civic duty; granaries were kept stocked and cisterns filled, but psychic defences were also held to be of supreme importance by the Orthodox faithful. The Virgin was the protector of the city; her icons were paraded along the walls at times of crisis and were considered to have saved the city during the siege of 717. They provided a confidence to equal the Koran.

None of the besieging armies that camped outside the land walls could break down these physical and psychological defences. The technology to storm the fortifications, the naval resources to blockade the sea and the patience to starve the citizens were not available to any would-be conqueror. The empire, though frequently stretched to

breaking point, showed remarkable resilience. The infrastructure of the city, the strength of the empire’s institutions and the lucky coincidence of outstanding leaders at moments of crisis made the eastern Roman Empire seem to both its citizens and its enemies likely to continue for ever.

Yet the experience of the Arab sieges marked the city deeply. People recognized in Islam an irreducible counterforce, something qualitatively different to other foes; their own prophecies about the Saracens – as the Arabs came to be known in Christendom – articulated their forebodings about the future of the world. One writer declared them to be the Fourth Beast of the Apocalypse that ‘will be the fourth kingdom on the earth, that will be most disastrous of all kingdoms, that will transform the entire earth into a desert’. And towards the end of the eleventh century, a second blow fell upon Byzantium at the hands of Islam. It happened so suddenly that no one at the time quite grasped its significance.

1 The Burning Sea

1

‘O Christ, ruler …’, quoted Sherrard, p. 11

2

‘In the name of Allah …’, quoted Akbar, p. 45

3

‘Tell him that …’, quoted ibid., p. 44

4

‘to wage the holy war by sea’, Ibn Khaldun, vol. 2, p. 40

5

‘like a flash …’, Anna Comnena, p. 402

6

‘burned the ships …’, quoted Tsangadas, p. 112

7

‘having lost many fighting …’, quoted ibid., p. 112

8

‘the Roman Empire was guarded by God’, Theophanes Confessor, p. 676

9

‘It is said that they even …’, ibid., p. 546

10

‘brought the sea water …’, ibid., p. 550

11

‘to announce God’s mighty deeds’, ibid., p. 550

12

‘God and the all-holy Virgin …’, ibid., p. 546

13

‘In the jihad …’, quoted Wintle, p. 245

14

‘the place that’s the vast …’, Ovid,

Tristia

, 1. 10

15

‘more numerous than …’, quoted Sherrard, p. 12

16

‘the city of the world’s desire’, quoted Mansel, p. 3

17

‘O what a splendid city …’, quoted Sherrard, p. 12

18

‘During this time …’, quoted ibid., p. 51

19

‘It seems not to rest …’, quoted ibid., p. 27

20

‘the golden stream … a drift of snow’, quoted Norwich, vol. 1, p. 202

21

‘We knew not whether …’, quoted Clark, p. 17

22

‘The city is full …’, quoted ibid., p. 14

23

‘They are introduced …’, quoted Sherrard, p. 74

24

‘will be the fourth kingdom …’, quoted Wheatcroft, p. 54