Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 (25 page)

Read Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

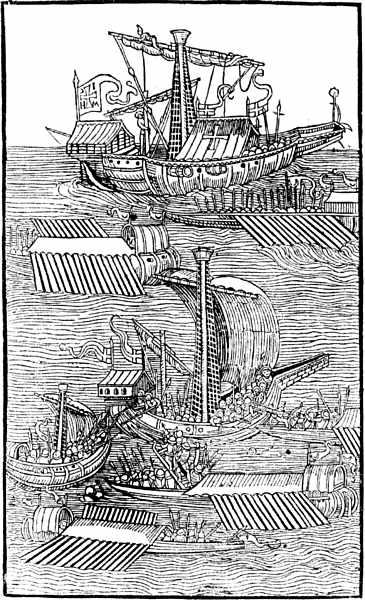

Ottoman galleys attacking Christian sailing ships

For two hours the Ottoman fleet grappled with its intractable foe in the heat of battle. Its soldiers and sailors fought bravely and with extraordinary passion, ‘like demons’, recorded Archbishop Leonard begrudgingly. Gradually, and despite heavy losses, the weight of numbers started to tell. One ship was surrounded by five triremes, another by thirty long boats, a third by forty barges filled with soldiers, like swarms of ants trying to down a huge beetle. When one long boat fell back exhausted or was sunk, leaving its armoured soldiers to be swept off in the current or clinging to spars, fresh boats rowed forward to tear at their prey. Baltaoglu’s trireme clung tenaciously to the heavier and less well-armed imperial transport, which ‘defended itself brilliantly, with its captain Francesco Lecanella rushing to help’. In time, however it became apparent to the captains of the Genoese ships that the transport would be taken without swift intervention. Somehow they managed to bring their ships up alongside in a practised manoeuvre and lash the four vessels together, so that they seemed to move, according to an observer, like four towers rising up among the swarming seething confusion of the grappling Ottoman fleet from a surface of wood so dense that ‘the water could hardly be seen’.

The spectators thronging the city walls and the ships within the boom watched helplessly as the matted raft of ships drifted slowly under the point of the Acropolis and towards the Galata shore. As the battle drew closer, Mehmet galloped down onto the foreshore, shouting excited instructions, threats and encouragement to his valiantly struggling men, then urging his horse into the shallow water in his desire to command the engagement. Baltaoglu was close enough now to hear and ignore his sultan’s bellowed instructions. The sun was setting. The battle had been raging for three hours. It seemed certain that Ottomans must win ‘for they took it in turns to fight, relieving each other, fresh men taking the places of the wounded or killed’. Sooner or later the supply of Christian missiles must give out and their energy would falter. And then something happened to shift the balance back again so suddenly that the watching Christians saw in it only the hand of God. The south wind picked up. Slowly the great square sails of the four towered carracks stirred and swelled and the ships started to

moved forward again in a block, impelled by the irresistible momentum of the wind. Gathering speed, they crashed through the surrounding wall of frail galleys and surged towards the mouth of the Horn. Mehmet shouted curses at his commander and ships ‘and tore his garments in his fury’ but by now night was falling and it was too late to pursue the ships further. Beside himself with rage at the humiliation of the spectacle, Mehmet ordered the fleet to withdraw to the Double Columns.

In the moonless dark, two Venetian galleys were dispatched from behind the boom, sounding two or three trumpets on each galley and with the men shouting wildly to convince their enemies that a force of ‘at least twenty galleys’ was putting to sea and to discourage any further pursuit. The galleys towed the sailing ships into the harbour to the ringing of church bells and the cheering of the citizens. Mehmet was ‘stunned. In silence, he whipped up his horse and rode away.’

9 A Wind from God

1

‘Battles on the sea …’, quoted Guilmartin, p. 22

2

‘thought that the fleet …’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli

, p. 38

3

‘long ships …’, ibid., p. 38

4

‘skilled seamen …’, ibid., p. 38

5

‘a great man …’, ibid., p. 43

6

‘homeland of defenders of the faith’, Pertusi,

La Caduta

, vol. 2, p. 256

7

‘with cries and cheering …’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli,

p. 39

8

‘the wind of divine …’, Pertusi,

La Caduta

, vol. 2, p. 256

9

‘we put ready for battle …’, Barbaro,

Giornale,

p. 19

10

‘in close array …’, Barbaro,

Diary,

p. 29

11

‘well armed …’, Barbaro,

Giornale,

p. 20

12

‘Seeing that we …’, ibid., p. 20

13

‘with determination’, ibid., p. 21

14

‘eager cries …’, Pertusi,

La Caduta

, vol. 1, p. 15

15

‘waiting hour after …’, Barbaro,

Giornale,

p. 22

16

‘wounding many …’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli,

p. 51

17

‘and inflicted …’, ibid., p. 51

18

‘in the East …’, Pertusi,

La Caduta

, vol. 1, p. lxxvi

19

‘either to take …’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli,

p. 53

20

‘many other weapons …’, ibid., p. 53

21

‘with ambition and …’ ibid., p. 53

22

‘with a great sounding …’, Barbaro,

Giornale

, p. 23

23

‘they fought from …’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli,

p. 53

24

‘shouted in a commanding voice’, ibid., p. 53

25

‘like dry land’, Doukas,

Fragmenta,

p. 269

26

‘they threw missiles …’, Leonard, p. 30

27

‘that the oars …’, Doukas,

Fragmenta,

p. 269

28

‘There was great …’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli,

p. 54

29

‘like demons’, Melville Jones, p. 21

30

‘defended itself brilliantly …’, Pertusi,

La Caduta

, vol. 1, p. 140

31

‘the water could hardly be seen’, Barbaro, p. 33

32

‘for they took it in turns …’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli

, p. 54

33

‘and tore his garments …’, Melville Jones, p. 22

34

‘at least twenty galleys’, Barbaro,

Giornale,

p. 24

35

‘stunned. In silence …’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli,

p. 55

20–28

APRIL

1453

Warfare is deception.

A saying attributed to the Prophet

The immediate consequences of the naval engagement in the Bosphorus were profound. A few short hours had tipped the psychological balance of the siege sharply and unexpectedly back to the defenders. The spring sea had provided a huge auditorium for the public humiliation of the Ottoman fleet, watched both by the Greek population thronging the walls and the right wing of the army with Mehmet on the shore opposite.

It was obvious to both sides that the massive new fleet, which had so stunned the Christians when it first appeared in the Straits, could not match the experience of Western seamanship. It had been thwarted by superior skill and equipment, the innate limitations of war galleys – and not a little luck. Without secure control of the sea, the struggle to subdue the city would be hard fought, whatever the sultan’s guns might achieve at the land walls.

Within the city, spirits were suddenly high again: ‘the ambitions of the sultan were thrown into confusion and his reputed power diminished, because so many of his triremes couldn’t by any means capture just one ship’. The ships not only brought much needed grain, arms and manpower, they had given the defenders precious hope. This small flotilla might be merely the precursor of a larger rescue fleet. And if

four ships were able to defy the Ottoman navy, what might a dozen well-armed galleys of the Italian republics not do to decide the final outcome? ‘This unhoped-for result revived their hopes and brought encouragement, and filled them with very favourable hopes, not only about what had happened, but also about their expectations for the future.’ In the fevered religious atmosphere of the conflict, such events were never just the practical contest of men and materials or the play of winds, they were clear evidence of the hand of God. ‘They prayed to their prophet Muhammad in vain,’ wrote the surgeon Nicolo Barbaro, ‘while our Eternal God heard the prayers of us Christians, so that we were victorious in this battle.’

Some time about now, it seems that Constantine, buoyed by this victory or the failure of the earlier Ottoman land attack, sensed that the moment was right to make a peace offer. He probably proposed a face-saving payment that would allow Mehmet to withdraw with honour, and he may have delivered it via Halil Pasha. Siege warfare involves a complex symbiosis between besieger and besieged and he was fully aware that outside the walls the Muslim camp was plunged into a corresponding mood of crisis. For the first time since the siege began, serious doubts were voiced. Constantinople remained obdurate – a ‘bone in the throat of Allah’ – like the crusader castles. The city was a psychological as much as a military problem for the warriors of the Faith. The technological and cultural self-confidence needed to defeat the infidel and to overturn the deep pattern of history was suddenly fragile again and the death of the Prophet’s standard-bearer Ayyub at the walls eight centuries before would have been keenly in mind. ‘This event’, wrote the Ottoman chronicler Tursun Bey, ‘caused despair and disorder in the ranks of the Muslims … the army was split into groups.’

It was a defining moment for the self-belief of the cause. In practical terms, the possibility of a long-drawn-out siege, with all its problems for logistics and morale, the likelihood of disease – the scourge of medieval besieging armies – and the chance that men might slip away, must have loomed larger on the evening of 20 April. It spelled clear personal danger for Mehmet’s authority. An open revolt by the Janissaries became an idea on the fringe of possibility. Mehmet never commanded the love of his standing army as his father Murat had done. It had revolted against the petulant young sultan twice before and this was remembered, particularly by Halil Pasha, the chief vizier.

These feelings were brought into sharp focus that evening when Mehmet received a letter from Sheikh Akshemsettin, his spiritual adviser and a leading religious figure in the Ottoman camp. It presented the mood of the army and brought a warning:

This event … has caused us great pain and low morale. Not having taken this opportunity has meant that certain adverse developments have taken place: one … is that the infidels have rejoiced and held a tumultuous demonstration; a second is the assertion that your noble majesty has shown little good judgement and ability in having your orders carried out … severe punishments will be required … if this punishment is not carried out now … the troops will not give their full support when the trenches must be levelled and the order is given for the final attack.

The sheikh also pointed out that the defeat threatened to undermine the religious faith of the men. ‘I have been accused of having failed in my prayers’, he went on, ‘and that my prophecies have been shown to be unfounded … you must take care of this so that in the end we shall not be obliged to withdraw in shame and disappointment.’