CSS: The Definitive Guide, 3rd Edition (16 page)

Read CSS: The Definitive Guide, 3rd Edition Online

Authors: Eric A. Meyer

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Web / Page Design

As you might expect,lighterworks in just the same way, except it causes the user agent to

move down the weight scale instead of up. With a quick modification of the previous

example, you can see this very clearly:

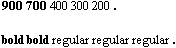

/* assume only two faces for this example: 'Regular' and 'Bold' */

p {font-weight: 900;} /* as bold as possible, which will look 'bold' */

p span {font-weight: 700;} /* this will also be bold */

strong {font-weight: lighter;} /* lighter than its parent */

b {font-weight: lighter;} /* lighter still */

900 700 400 300 200

.

bold bold regular regular

regular .

Ignoring the fact that this would be entirely counterintuitive, what you see in

Figure 5-8

is that the main paragraph

text has a weight of900. When thestrongtext is set to belighter, it evaluates to the next-lighter face, which is the regular

face, or400(the same asnormal) on the numeric scale. The next step down is to300, which is the same asnormalsince no lighter faces exist. From there, the user agent can

reduce the weight only one numeric step at a time until it reaches100(which it doesn't do in the example). The second

paragraph shows which text will be bold and which will be regular.

Figure 5-8. Making text lighter

The methods for determining font size are both very

familiar and very different.

font-size

- Values:

xx-small|x-small|small|medium|large|x-large|xx-large|smaller|larger|| | inherit- Initial value:

medium- Applies to:

All elements

- Inherited:

Yes

- Percentages:

Calculated with respect to the parent element's font size

- Computed value:

An absolute length

In a fashion very similar to thefont-weightkeywordsbolderandlighter, the propertyfont-sizehas

relative-size keywords calledlargerandsmaller. Much like what we saw with relative font weights,

these keywords cause the computed value offont-sizeto move up and down a scale of size values, which you'll need to understand before you

can explorelargerandsmaller. First, though, we need to examine how fonts are sized in the

first place.

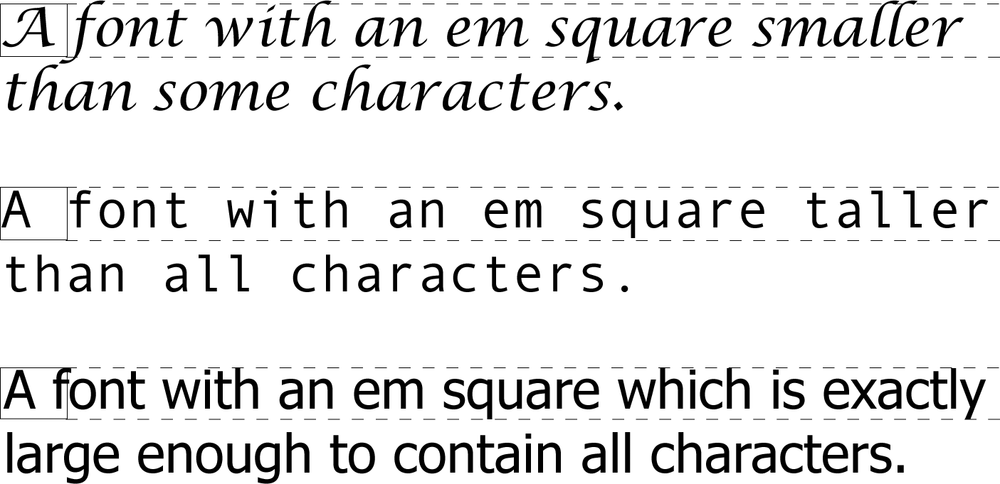

In fact, the actual relation of thefont-sizeproperty to what you see rendered is determined by the font's designer. This

relationship is set as an

em square

(some call it an

em box

)

within the font itself. This em square (and thus the font

size) doesn't have to refer to any boundaries established by the characters in a font.

Instead, it refers to the distance between baselines when the font is set without any

extra leading (line-heightin CSS). It is quite

possible for fonts to have characters that are taller than the default distance between

baselines. For that matter, a font might be defined such that all of its characters are

smaller than its em square, as many fonts do. Some hypothetical examples are shown in

Figure 5-9

.

Figure 5-9. Font characters and em squares

Thus, the effect offont-sizeis to provide a size

for the em box of a given font. This does not guarantee that any of the actual displayed

characters will be this size.

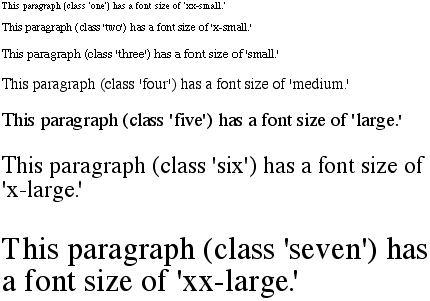

Having established all of that, we turn now to the

absolute-size keywords. There are seven absolute-size values forfont-size:xx-small,x-small,small,medium,large,x-large, andxx-large. These are not defined precisely, but are

relative to each other, as

Figure 5-10

demonstrates:

p.one {font-size: xx-small;}

p.two {font-size: x-small;}

p.three {font-size: small;}

p.four {font-size: medium;}

p.five {font-size: large;}

p.six {font-size: x-large;}

p.seven {font-size: xx-large;}

Figure 5-10. Absolute font sizes

According to the CSS1 specification, the difference (or

scaling

factor

)

between one absolute size and the next should be about

1.5 going up the ladder, or 0.66 going down. Thus, ifmediumis the same as10px, thenlargeshould be the same as15px. On the other hand, the scaling factor does not

have to be 1.5; not only might it be different for different user agents, but it was

changed to a factor somewhere between 1.0 and 1.2 in CSS2.

Working from the assumption thatmediumequals16px, for different scaling factors, we get the

absolute sizes shown in

Table 5-3

. (The

following values are approximations, of course.)

Table 5-3. Scaling factors translated to pixels

Keyword | Scaling: 1.5 | Scaling: 1.2 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Further complicating the situation is the fact that different user agents have

assigned the "default" font size to different absolute keywords. Take the Version 4

browsers as an example: Navigator 4 makesmediumthe same size as unstyled text, whereas Internet Explorer 4 assumes thatsmalltext is equivalent in size to unstyled text.

Despite the fact that the default value forfont-styleis supposed to bemedium,

IE4's behavior may be wrong, but not quite so wrong as it might first

appear.

[

*

]

Fortunately, IE6 fixed the problem, at least when the browser is in

standards mode, and treatsmediumas the

default.

Comparatively speaking, the keywordslargerandsmallerare simple: they cause the size of an element to be shifted up or down the

absolute-size scale, relative to their parent element, using the same scaling factor

employed to calculate absolute sizes. In other words, if the browser used a scaling

factor of 1.2 for absolute sizes, then it should use the same factor when applying

relative-size keywords:

p {font-size: medium;}

strong, em {font-size: larger;}

This paragraph element contains a strong-emphasis element

which itself contains an emphasis element that also contains

a strong element.

medium large x-large

xx-large

Unlike the relative values for weight, the relative-size values are not

necessarily constrained to the limits of the absolute-size range. Thus, a font's size

can be pushed beyond the sizes forxx-smallandxx-large. For example:

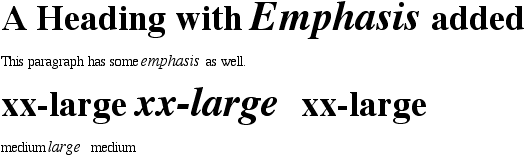

h1 {font-size: xx-large;}

em {font-size: larger;}

A Heading with Emphasis added

This paragraph has some emphasis as well.

As you can see in

Figure 5-11

, the

emphasized text in theh1element is slightly

larger thanxx-large. The amount of scaling is

left up to the user agent, with the scaling factor of 1.2 being preferred. Theemtext in the paragraph, of course, is shifted

one slot up the absolute-size scale (large).

Figure 5-11. Relative font sizing at the edges of the absolute sizes

User agents are not required to increase or decrease font size beyond the

limits of the absolute-size keywords.

In a way, percentage values are very similar to the

relative-size keywords. A percentage value is always computed in terms of whatever

size is inherited from an element's parent. Percentages, unlike the relative-size

keywords, permit much finer control over the computed font size. Consider the

following example, illustrated in

Figure

5-12

:

body {font-size: 15px;}

p {font-size: 12px;}

em {font-size: 120%;}

strong {font-size: 135%;}

small, .fnote {font-size: 70%;}

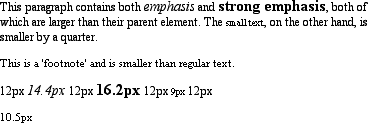

This paragraph contains both emphasis and strong

emphasis, both of which are larger than their parent element.

The small text, on the other hand, is smaller by a quarter.

This is a 'footnote' and is smaller than regular text.

12px 14.4px 12px 16.2px 12px

9px 12px

10.5px

Figure 5-12. Throwing percentages into the mix

In this example, the exact pixel size values are shown. In practice, a web browser

would very likely round the values off to the nearest whole-number pixel, such as14px, although advanced user agents may

approximate fractional pixels through anti-aliasing or when printing the document.

For otherfont-sizevalues, the browser may (or

may not) preserve fractions.

Incidentally, CSS defines the length valueemto be equivalent to percentage values, in the sense that1emis the same as100%when sizing

fonts. Thus, the following would yield identical results (assuming both paragraphs

have the same parent element):

p.one {font-size: 166%;}

p.two {font-size: 1.6em;}

When usingemmeasurements, the same principles

apply as with percentages, such as the inheritance of computed sizes, and so

forth.