CSS: The Definitive Guide, 3rd Edition (57 page)

Read CSS: The Definitive Guide, 3rd Edition Online

Authors: Eric A. Meyer

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Web / Page Design

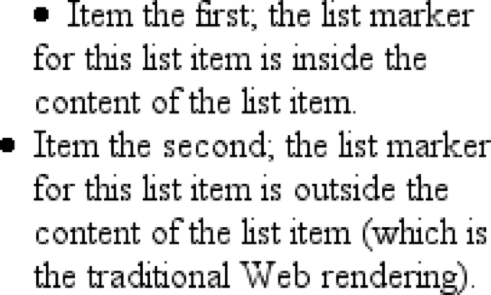

There is one other thing you can do to influence the

appearance of list items under CSS2.1: decide whether the marker appears outside or

inside the content of the list item. This is accomplished withlist-style-position.

list-style-position

- Values:

inside|outside|inherit- Initial value:

outside- Applies to:

Elements whose

displayvalue islist-item- Inherited:

Yes

- Computed value:

As specified

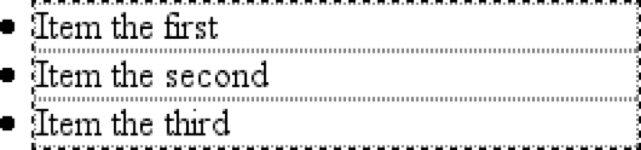

If a marker's position is set tooutside(the

default), it will appear the way list items always have on the Web. Should you desire

a slightly different appearance, though, you can pull the marker in toward the

content by setting the value toinside. This

causes the marker to be placed "inside" the list item's content. The exact way this

happens is undefined, but

Figure 12-5

shows one possibility:

li.first {list-style-position: inside;}

li.second {list-style-position: outside;}

Figure 12-5. Placing the markers inside and outside list items

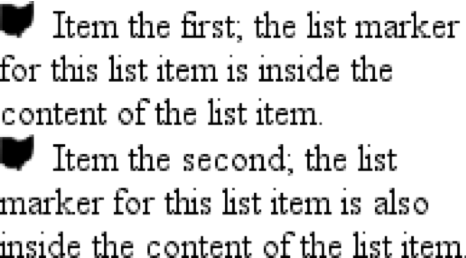

For brevity's sake, you can combine the three list-style properties into a

convenient single property:list-style.

list-style

- Values:

[

|| || ] | inherit- Initial value:

Refer to individual properties

- Applies to:

Elements whose

displayvalue islist-item- Inherited:

Yes

- Computed value:

See individual properties

For example:

li {list-style: url(ohio.gif) square inside;}

As you can see in

Figure 12-6

, all

three values are applied to the list items.

Figure 12-6. Bringing it all together

The values forlist-stylecan be listed in any

order, and any of them can be omitted. As long as one is present, the rest will fill

in their default values. For instance, the following two rules will have the same

visual effect:

li.norm {list-style: url(img42.gif);}

li.odd {list-style: url(img42.gif) disc outside;} /* the same thing */

They will also override any previous rules in the same way. For example:

li {list-style-type: square;}

li.norm {list-style: url(img42.gif);}

li.odd {list-style: url(img42.gif) disc outside;} /* the same thing */

The result will be the same as that in

Figure

12-6

because the impliedlist-style-typevalue ofdiscfor the ruleli.normwill override the previous declared value ofsquare, just as the explicit value ofdiscoverrides it in ruleli.odd.

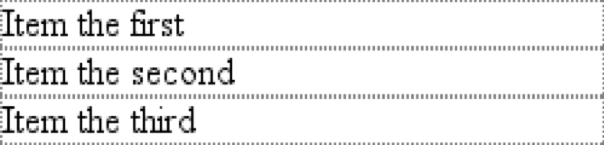

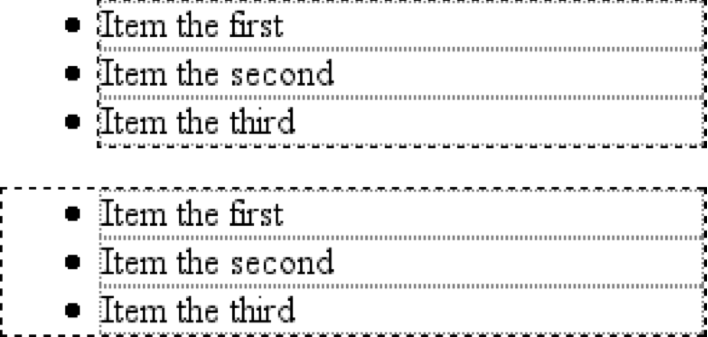

Now that we've

looked at the basics of styling list markers, let's consider how lists are laid out

in various browsers. We'll start with a set of three list items devoid of any markers

and not yet placed within a list, as shown in

Figure 12-7

.

Figure 12-7. Three list items

The border around the list items shows them to be, essentially, like a block-level

element. Indeed, the valuelist-itemis defined to

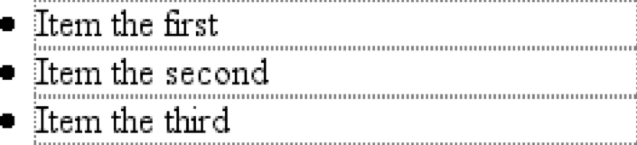

generate a block box. Now let's add markers, as illustrated in

Figure 12-8

.

Figure 12-8. Markers are added

The distance between the marker and the list item's content is not defined by CSS,

and CSS2.1 does not provide a way to affect that distance. Interestingly, CSS2 does,

which is a subject briefly covered in the sidebar "

List-Marker Positioning

."

With the markers outside the list items' content, they don't affect the layout of

other elements, nor do they really even affect the layout of the list items

themselves. They just hang a certain distance from the edge of the content, and

wherever the content edge goes, the marker will follow. The behavior of the marker

works much as though the marker were absolutely positioned in relation to the

list-item content, something likeposition:absolute; left:-1.5em;. When the marker is inside, it acts like an inline element at

the beginning of the content.

So far, you have yet to add an actual list container; in other words, there is

neither aulnor anolelement represented in the figures. You can add one to the mix, as

shown in

Figure 12-9

(it's represented by

a dashed border).

Figure 12-9. Adding a list element

Like the list items, the list element is a block box, one that encompasses its

descendant elements. As you can see, however, the markers are not only placed outside

the list item contents, but also outside the content area of the list element. The

usual "indentation" you expect from lists has not yet been specified.

Most browsers, as of this writing, indent list items by setting either padding or

margins for the containing list element. For example, the user agent might apply a

rule such as:

ul, ol {margin-left: 40px;}

This is the rule employed by Internet Explorer and Opera (see

Figure 12-9

). Most Gecko-based browsers, on

the other hand, use a rule like this:

ul, ol {padding-left: 40px;}

Neither is incorrect, but the discrepancy can lead to problems if you want to

eliminate the indentation of the list items.

Figure 12-10

shows the difference between the two approaches.

Figure 12-10. Margins and padding as indentation devices

The distance of40pxis a relic of early web

browsers, which indented lists by a pixel amount. A better value would be

something like2.5em, since this scales the

indentation along with changes in the text size.

For authors who want to change the indentation distance of lists, I strongly

recommend that you specify both padding and margins to ensure cross-browser

compatibility. For example, if you want to use padding to indent a list, use this

rule:

ul {margin-left: 0; padding-left: 1em;}

If you prefer margins, write something like this instead:

ul {margin-left: 1em; padding-left: 0;}

In either case, remember that the markers will be placed relative to the contents

of the list items, and may therefore "hang" outside the main text of a document, or

even beyond the edge of the browser window.

CSS2 and CSS2.1 include a new feature called

generated content

.

This is content created by the browser but not represented

either by markup or content.

For example, list markers are generated content. There is nothing in the markup of a

list item that directly represents the markers, and you, the author, do not have to

write the markers into your document's content. The browser simply generates the

appropriate marker automatically. For unordered lists, the marker is a bullet of some

kind, such as a circle, disc, or square. In ordered lists, the marker is a counter that

increments by one for each successive list item.

List-Marker Positioning

One feature many authors request is the ability to control the space between a

marker and the content of a list item. CSS2 defined ways to do this, including a

property calledmarker-offsetand adisplayvalue ofmarker. Implementation experience revealed this to be a clumsy approach,

and these features were removed in CSS2.1

As of this writing, the current working draft of the CSS3 Lists module defines a

new and more compact way to affect marker placement, which is the::markerpseudo-element. Assuming that the module does

not change before becoming a full Recommendation, you may someday be able to write

rules such asli::marker {margin-right:0.125em;}in order to get markers snugly against the

content of list items without actually bringing them inside.

To understand how you can affect list markers and customize the counting of ordered

lists (or anything else!), you must first look at more basic generated

content.

As of this writing, no version of Internet Explorer supports generated

content.

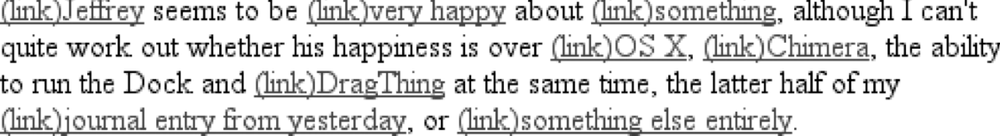

To insert generated content into the document, use

the:beforeand:afterpseudo-elements. These place generated content before or after the

content of an element by way of the content property (described in the next section).

For example, you might want to precede every hyperlink with the text "(link)" to

mark them for printing. This is accomplished with a rule like the following, which

has the effect shown in

Figure 12-11

:

a[href]:before {content: "(link)";}

Figure 12-11. Generating text content

Note that there isn't a space between the generated content and the element

content. This is because the value of content in the previous example doesn't include

a space. You could modify the declaration as follows to make sure there's a space

between generated and actual content:

a[href]:before {content: "(link) ";}

It's a small difference but an important one.

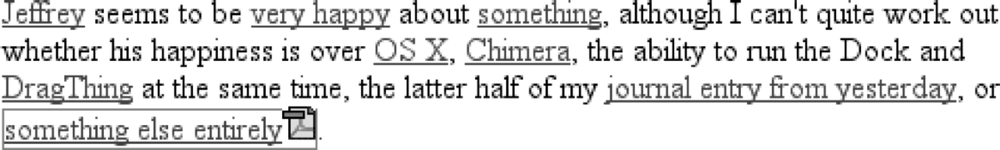

In a similar manner, you might choose to insert a small icon at the end of links

to PDF documents. The rule to accomplish this would look something like:

a.pdf-doc:after {content: url(pdf-doc-icon.gif);}

Suppose you want to further style such links by placing a border around them. This

is done with a second rule:

a.pdf-doc {border: 1px solid gray;}

The result of these two rules is illustrated in

Figure 12-12

.

Figure 12-12. Generating icons

Notice how the link border extends around the generated content, just as the link

underline extended under the "(link)" text in

Figure 12-11

. This happens because generated content is placed inside the

element box of the element. As of CSS2.1, there isn't a way to place generated

content outside the element box, other than list markers.

You might think that positioning would do the trick, except CSS2 and CSS2.1

specifically prohibit the floating or positioning of:beforeand:aftercontent. List-style

properties, along with table properties, are similarly prohibited. In addition, the

following restrictions apply:

If the subject of a

:beforeor:afterselector is a block-level element, then the

propertydisplaycan accept only the valuesnone,inline,block, andmarker. Any other value is treated asblock.If the subject of a

:beforeor:afterselector is an inline-level element, then

the propertydisplaycan accept only the

valuesnoneandinline. Any other value is treated asinline.

For example, consider:

em:after {content: " (!) "; display: block;}

Sinceemis an inline element, the generated

content cannot be made block-level. The valueblockis therefore reset toinline. In

this next example, however, the generated content is made block-level because the

target element is also block-level:

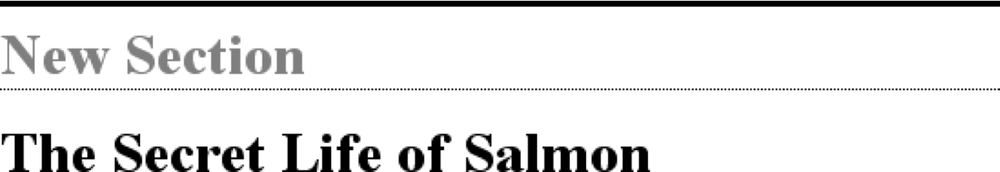

h1:before {content: "New Section"; display: block; color: gray;}

The result is illustrated in

Figure

12-13

.

Figure 12-13. Generating block-level content

One interesting aspect of generated content is that it inherits values from the

element to which it's been attached. Thus, given the following rules, the generated

text will be green, the same as the content of the paragraphs:

p {color: green;}

p:before {content: "::: ";}

If you want the generated text to be purple instead, a simple declaration will

suffice:

p:before {content: "::: "; color: purple;}

Such value inheritance happens only with inherited properties, of course. This is

worth noting because it influences how certain effects must be approached. Consider:

h1 {border-top: 3px solid black; padding-top: 0.25em;}

h1:before {content: "New Section"; display: block; color: gray;

border-bottom: 1px dotted black; margin-bottom: 0.5em;}

Since the generated content is placed inside the element box of theh1, it will be placed under the top border of the

element. It would also be placed within any padding, as shown in

Figure 12-14

.

Figure 12-14. Taking placement into account

The bottom margin of the generated content, which has been made block-level,

pushes the actual content of the element downward by half an em. In every sense, the

effect of the generated content in this example is to break up theh1element into two pieces: the generated-content box

and the actual content box. This happens because the generated content hasdisplay:block. If

you were to change it todisplay:inline, the effect would be as shown in

Figure 12-15

:

h1 {border-top: 3px solid black; padding-top: 0.25em;}

h1:before {content: "New Section"; display: inline; color: gray;

border-bottom: 1px dotted black; margin-bottom: 0.5em;}

Figure 12-15. Changing the generated content to be inline

Note how the borders are placed and how the top padding is still honored. So is

the bottom margin on the generated content, but since the generated content is now

inline and margins don't affect line height, the margin has no visible effect.

With the basics of generating content established, let's take a closer look at the

way the actual generated content is specified.

If you're going to generate

content, you need a way to describe the content to be generated. As you've already

seen, this is handled with thecontentproperty,

but there's a great deal more to this property than you've seen thus far.

content

- Values:

normal| [| | | attr()|open-quote|close-quote|no-open-quote|no-close-quote]+ |inherit- Initial value:

normal- Applies to:

:beforeand:afterpseudo-elements- Inherited:

No

- Computed value:

For

values, an absolute URI; for attribute references, the

resulting string; otherwise, as specified

You've already seen string and URI values in action, and counters will be covered

later in this chapter. Let's talk about strings and URIs in a little more detail

before we take a look at theattr( )and quote

values.

String values are presented literally, even if they contain what would otherwise

be markup of some kind. Therefore, the following rule would be inserted verbatim into

the document, as shown in

Figure 12-16

:

h2:before {content: "¶ "; color: gray;}

Figure 12-16. Strings are displayed verbatim

This means that if you want a newline (return) as part of your generated content,

you can't use

string\A, which is the CSS way of representing a

newline (based on the Unicode linefeed character, which is hexadecimal positionA). Conversely, if you have a long string value

and need to break it up over multiple lines, you escape out the linefeeds with the\character. These are both demonstrated by the

following rule and illustrated in

Figure

12-17

:

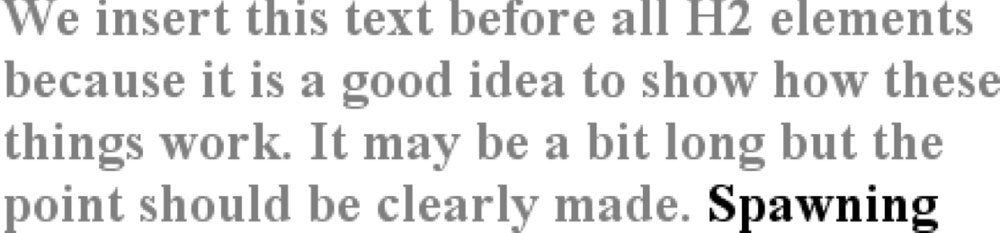

h2:before {content: "We insert this text before all H2 elements because \

it is a good idea to show how these things work. It may be a bit long \

but the point should be clearly made. "; color: gray;}

Figure 12-17. Inserting and suppressing newlines

You can also use escapes to refer to hexadecimal Unicode values, such as\00AB.

As of this writing, support for inserting escaped content

such as\Aand\00ABis not very widespread, even among

those browsers that support some generated content.

With URI values, you simply point to an external resource (an image, movie, sound

clip, or anything else the user agent supports), which is then inserted into the

document in the appropriate place. If the user agent can't support the resource you

point it to for any reason—say, you try to insert an SVG image into a browser that

doesn't understand SVG, or try to insert a movie into a document when it's being

printed—then the user agent is required to ignore the resource completely, and

nothing will be inserted.

values

There

are situations where you might want to take the value of an element's attribute

and make it a part of the document display. To pick a simple example, you can

place the value of every link'shrefattribute

immediately after the links, like

this:

a[href] {content: attr(href);}

Again,

this leads to the problem of the generated content running smack into the actual

content. To solve this, add some string values to the declaration, with the result

shown in

Figure

12-18

:

a[href] {content: " [" attr(href) "]";}

Figure 12-18. Inserting URLs

This can be useful for print style sheets, as an example. Any

attribute value can be inserted as generated content:alttext,classoridvalues—anything. An author might choose to make

the citation information explicit for a block quote, like

this:

blockquote:after {content: "(" attr(cite) ")"; display: block;

text-align: right; font-style: italic;}

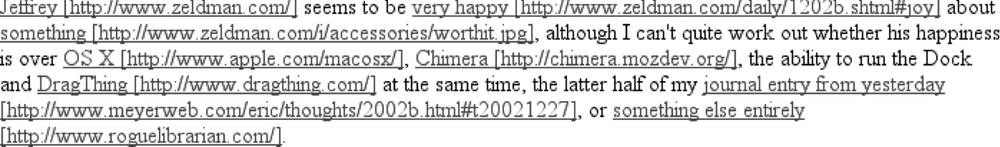

For

that matter, a more complicated rule might reveal the text- and link-color values

for a legacy

document:

body:before {content: "Text: " attr(text) " | Link: " attr(link)

" | Visited: " attr(vlink) " | Active: " attr(alink);

display: block; padding: 0.33em;

border: 1px solid black; text-align: center;}

Note

that if an attribute doesn't exist, an empty string is put in its place. This is

what happens in

Figure 12-19

, in

which the previous example is applied to a document whosebodyelement has noalinkattribute.

Figure 12-19. Missing attributes are skipped

The text "Active: " (including the trailing space) is inserted into

the document, as you can see, but there is nothing following it. This is

convenient in situations where you want to insert the value of an attribute only

when it exists.

CSS2.x defines the returned value of an attribute reference as an unparsed

string. Therefore, if the value of an attribute contains markup or character

entities, they will be displayed verbatim.

quotes

A specialized form of generated content is the

quotation mark, and CSS2.x provides a powerful way to manage both quotes and their

nesting behavior. This is possible due to the pairing of content values likeopen-quoteand the propertyquotes.

quotes

- Values:

[

]+ | none|inherit- Initial value:

User agent-dependent

- Applies to:

All elements

- Inherited:

Yes

- Computed value:

As specified

Upon studying the value syntax, we find that other than the keywordsnoneandinherit, the only valid value is one or more

pairs

of strings. The first string of the pair defines the open-quote symbol, and the

second defines the close-quote symbol. Therefore, of the following two

declarations, only the first is

valid:

quotes: '"' "'"; /* valid */

quotes: '"'; /* NOT VALID */

The

first rule also illustrates one way to put string quotes around the strings

themselves. The double quotation marks are surrounded by single quotation marks,

and vice versa.

Let's look at a simple example. Suppose you're

creating an XML format to store a list of favorite quotations. Here's one entry in

the

list:

Ralph Waldo Emerson

To

present the data in a useful way, you could employ the following rules, with the

result shown in

Figure

12-20

:

quotation: display: block;}

quote {quotes: '"' '"';}

quote:before {content: open-quote;}

quote:after {content: close-quote;}

quotee:before {content: " (";}

quotee:after {content: ")";}

Figure 12-20. Inserting quotes and other content

The valuesopen-quoteandclose-quoteare used to insert whatever quoting

symbols are appropriate (since different languages have different quotation

marks). They use the value of quotes to determine how they should work. Thus, the

quotation begins and ends with a double quotation mark.

If you want to

use "curly quotes" instead of the plain vertical-line quotation marks, as is

common in most print media, thequoterule

would

read:

quote {quotes: '\201C' '\201D';}

This

uses the hexadecimal Unicode positions for the "curly quote" symbols and, if

applied to the previous quotation, would surround Emerson's quote with curly

quotes instead of the straight quotes in

Figure 12-20

.

Withquotes, you can define quotation patterns to as many nesting levels as

you like. In English, for example, a common practice is to start out with a double

quotation mark, and a quotation nested inside the first one gets single quotation

marks. This can be recreated with "curly" quotation marks using the following

rules:

quotation: display: block;}

quote {quotes: '\201C' '\201D' '\2018' '\2019';}

quote:before, q:before{content: open-quote;}

quote:after, q:after {content: close-quote;}

When

applied to the following markup, these rules will have the effect shown in

Figure

12-21

:

be light!

Figure 12-21. Nested curly quotes

In a case where the nested level of quotation marks is greater than

the number of defined pairs, the last pair is reused for the deeper levels. Thus,

if you had applied the following rule to the markup shown in

Figure 12-21

, the inner quote would have

had double quotation marks, the same as the outer

quote:

quote {quotes: '\201C' '\201D';}

Generated

quotes make possible one other common typographic effect. In situations where

there are several paragraphs of quoted text, theclose-quoteof each paragraph is often omitted; only the opening

quote marks are shown, with the exception of the last paragraph. This can be

recreated using theno-close-quotevalue:

blockquote {quotes: '"' '"' "'" "'" '"' '"';}

blockquote p:before {content: open-quote;}

blockquote p:after {content: no-close-quote;}

This

will start each paragraph with a double quotation mark but no closing mark. This

is true of the last paragraph as well, so if you need to add a closing quote mark,

you'd need to class the final paragraph and declare aclose-quotefor its:aftercontent.

This value is important because it decrements the quotation

nesting level without actually generating a symbol. This is why each paragraph

starts with a double quotation mark, instead of alternating between double and

single marks until the third paragraph is reached.no-close-quotecloses the quotation nesting at the end of each

paragraph, and thus every paragraph starts at the same nesting

level.

This is significant because, as the CSS2.1 specification notes,

"Quoting depth is independent of the nesting of the source document or the

formatting structure." In other words, when you start a quotation level, it

persists across elements until aclose-quoteis

encountered, and the quote nesting level is decremented.

For the sake

of completeness, there is ano-open-quotekeyword, which has a symmetrical effect tono-close-quote. This keyword increments the quotation nesting level by

one but does not generate a symbol.