CSS: The Definitive Guide, 3rd Edition (7 page)

Read CSS: The Definitive Guide, 3rd Edition Online

Authors: Eric A. Meyer

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Web / Page Design

The last type of attribute selector, the

particular attribute selector, is easier to show than it is to describe. Consider the

following rule:

*[lang|="en"] {color: white;}

This rule will select any element whoselangattribute is equal toenor begins withen-. Therefore, the first three elements in the

following example markup would be selected, but the last two would not:

Hello!Greetings!

G'day!Bonjour!

Jrooana!

In general, the form[att|="val"]can be used

for any attribute and its values. Let's say you have a series of figures in an HTML

document, each of which has a filename like

figure-1.gif

and

figure-3.jpg

. You can match all of these images using the

following selector:

img[src|="figure"] {border: 1px solid gray;}

The most common use for this type of attribute selector is to match language

values, as demonstrated later in this chapter.

As I've mentioned before, CSS is powerful

because it uses the structure of HTML documents to determine appropriate styles and how

to apply them. That's only part of the story since it implies that such determinations

are the only way CSS uses document structure. Structure plays a much larger role in the

way styles are applied to a document. Let's take a moment to discuss structure before

moving on to more powerful forms of selection.

To understand the

relationship between selectors and documents, you need to once again examine how

documents are structured. Consider this very simple HTML document:

Meerkat Central

Meerkat Central

Welcome to Meerkat Central, the best meerkat web site

on the entire Internet!

- We offer:

- Detailed information on how to adopt a meerkat

- Tips for living with a meerkat

- Fun things to do with a meerkat, including:

- Playing fetch

- Digging for food

- Hide and seek

- ...and so much more!

Questions? Contact us!

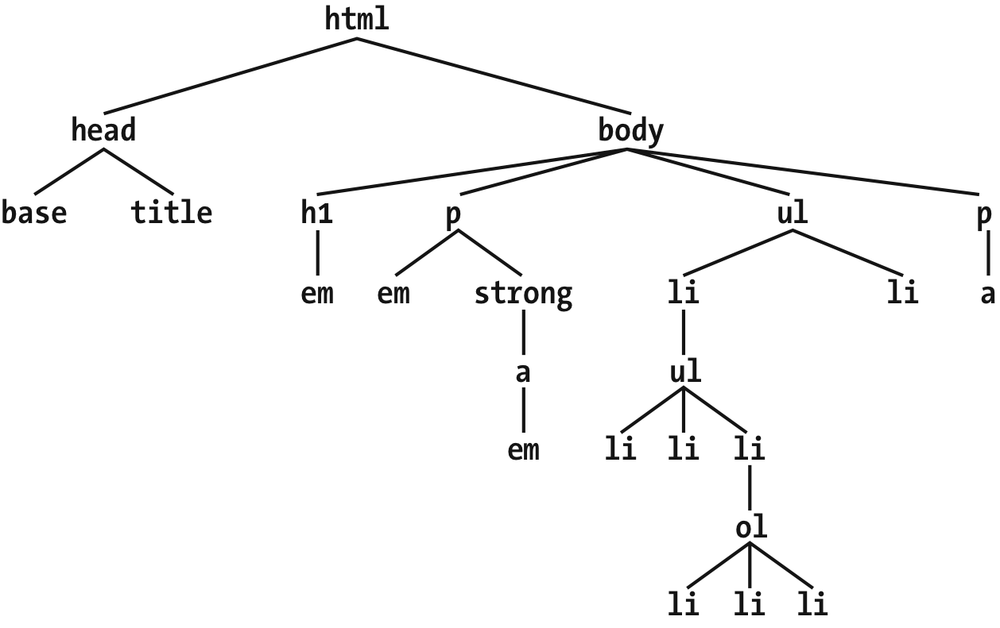

Much of the power of CSS is based on the

parent-child

relationship

of elements. HTML

documents (actually, most structured documents of any kind) are based on a hierarchy

of

elements, which is visible in the "tree" view of the document (see

Figure 2-14

). In this hierarchy, each

element fits somewhere into the overall structure of the document. Every element in

the document is either the

parent

or the

child

of another element, and it's often both.

Figure 2-14. A document tree structure

An element is said to be the parent of another element if it appears directly

above that element in the document hierarchy. For example, in

Figure 2-14

, the firstpelement is parent to theemandstrongelements, whilestrongis parent to ananchorelement, which is itself parent to anotheremelement. Conversely, an element is the child of another element if

it is directly beneath the other element. Thus, the anchor element in

Figure 2-14

is a child of thestrongelement, which is in turn child to thepelement, and so on.

The terms parent and child are specific applications of the terms

ancestor

and

descendant

. There is a

difference between them: in the tree view, if an element is exactly one level above

another, then they have a parent-child relationship. If the path from one element to

another continues through two or more levels, the elements have an

ancestor-descendant relationship, but not a parent-child relationship. (Of course, a

child is also a descendant, and a parent is an ancestor.) In

Figure 2-14

, the firstulelement is parent to twolielements, but the firstulis also

the ancestor of every element descended from itslielement, all the way down to the most deeply nestedlielements.

Also, in

Figure 2-14

, there is an

anchor that is a child ofstrong, but also a

descendant ofparagraph,body, andhtmlelements. Thebodyelement is an ancestor of everything that

the browser will display by default, and thehtmlelement is ancestor to the entire document. For this reason, thehtmlelement is also called the

root

element

.

The first benefit of understanding this model is the

ability to define

descendant selectors

(also known as

contextual selectors

).

Defining descendant selectors is the act of creating

rules that operate in certain structural circumstances but not others. As an example,

let's say you want to style only thoseemelements

that are descended fromh1elements. You could put

aclassattribute on everyemelement found within anh1, but that's almost as time-consuming as using thefonttag. It's obviously far more efficient to declare

rules that match onlyemelements that are found

insideh1elements.

To do so, write the following:

h1 em {color: gray;}

This rule will make gray any text in anemelement that is the descendant of anh1element.

Otheremtext, such as that found in a paragraph

or a block quote, will not be selected by this rule.

Figure 2-15

makes this clear.

Figure 2-15. Selecting an element based on its context

In a descendant selector, the selector side of a rule is composed of two or more

space-separated selectors. The space between the selectors is an example of a

combinator

. Each space combinator can be translated as "found

within," "which is part of," or "that is a descendant of," but only if you read the

selector right to left. Thus,h1 emcan be

translated as, "Anyemelement that is a

descendant of anh1element." (To read the

selector left to right, you might phrase it something like, "Anyh1that contains anemwill have the following styles applied to theem.")

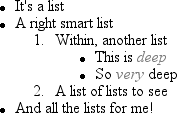

You aren't limited to two selectors, of course. For example:

ul ol ul em {color: gray;}

In this case, as

Figure 2-16

shows,

any emphasized text that is part of an unordered list that is part of an ordered list

that is itself part of an unordered list (yes, this is correct) will be gray. This is

obviously a very specific selection criterion.

Figure 2-16. A very specific descendant selector

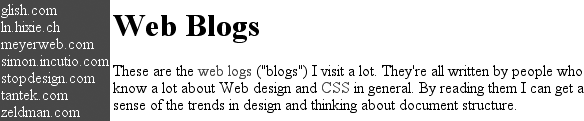

Descendant selectors can be extremely powerful. They make possible what could

never be done in HTML—at least not without oodles offonttags. Let's consider a common example. Assume you have a document

with a sidebar and a main area. The sidebar has a blue background, the main area has

a white background, and both areas include lists of links. You can't set all links to

be blue because they'd be impossible to read in the sidebar.

The solution: descendant selectors. In this case, you give the table cell that

contains your sidebar a class ofsidebar, and

assign the main area a class ofmain. Then, you

write styles like this:

td.sidebar {background: blue;}

td.main {background: white;}

td.sidebar a:link {color: white;}

td.main a:link {color: blue;}

Figure 2-17

shows the result.

Figure 2-17. Using descendant selectors to apply different styles to the same type of

element

:linkrefers to links to resources that haven't

been visited. We'll talk about it in detail later in this chapter.

Here's another example: let's say that you want gray to be the text color of anyb(boldface) element that is part of ablockquote, and also for any bold text that is found in

a normal paragraph:

blockquote b, p b {color: gray;}

The result is that the text withinbelements

that are descended from paragraphs or block quotes will be gray.

One overlooked aspect of descendant selectors is that the degree of separation

between two elements can be practically infinite. For example, if you writeul em, that syntax will select anyemelement descended from aulelement, no matter how deeply nested theemmay be. Thus,ul emwould select theemelement in the following markup:

- List item 1

- List item 1-1

- List item 1-2

- List item 1-3

- List item 1-3-1

- List item 1-3-2

- List item 1-3-3

- List item 1-4

In some cases, you don't want to select an

arbitrarily descended element; rather, you want to narrow your range to select an

element that is a child of another element. You might, for example, want to select astrongelement only if it is a child (as

opposed to a descendant) of anh1element. To do

this, you use the child combinator,

which is the

greater-than symbol (>):

h1 > strong {color: red;}

This rule will make red thestrongelement

shown in the firsth1below, but not the second:

This is very important.

This is really very important.

Read right to left, the selectorh1 > strongtranslates as "selects anystrongelement that is

a child of anh1element." The child combinator is

optionally surrounded by whitespace. Thus,h1 > strong,, and

h1> strongh1>strongare

all equivalent. You can use or omit whitespace as you wish.

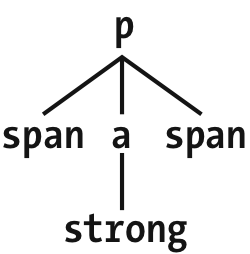

When viewing the document as a tree structure, it's easy to see that a child

selector restricts its matches to elements that are directly connected in the tree.

Figure 2-18

shows part of a document

tree.

Figure 2-18. A document tree fragment

In this tree fragment, you can easily pick out parent-child relationships. For

example, theaelement is parent to thestrong, but it is child to thepelement. You could match elements in this fragment with the selectorsp > aanda >, but not

strongp > strong, since

thestrongis a descendant of thepbut not its child.

You can also combine descendant and child combinations in the same selector. Thus,table.summary td > pwill select anypelement that is a child of atdelement that is itself descended from atableelement that has aclassattribute containing the wordsummary.