Drifting Home

DRIFTING HOME

PIERRE

BERTON

DRIFTING

HOME

A FAMILY'S VOYAGE OF DISCOVERY

DOWN THE WILD YUKON RIVER

Douglas & McIntyre

VANCOUVER/TORONTO

Copyright © 1973 by Pierre Berton Enterprises Ltd.

First Douglas & McIntyre edition 2002

02 03 04 05 06 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from CANCOPY (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency), Toronto, Ontario.

Douglas & McIntyre

2323 Quebec Street, Suite 201

Vancouver, British Columbia V5T 4s7

National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data

Berton, Pierre, 1920-

Drifting home

ISBN-print 1-55054-951-0

ISBN-ebook 978-1-926706-56-6

1. Berton, Pierre, 1920- 2. Yukon TerritoryâDescription and travel.

3. Yukon River (Yukon and Alaska)âDescription and travel.

4. Yukon TerritoryâHistoryâ1895-* I. Title.

FC40I7.3.B47 2002Â Â Â Â Â Â 917-19'1043Â Â Â Â Â Â c2002-910644-3

FI091.B47 2002

Cover design by Val Speidel

Cover photo by Paul Souders/Getty Images

Printed and bound in Canada by Friesens

Printed on acid-free paper

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Ministry of Tourism, Small Business and Culture, and the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) for its publishing activities.

CONTENTS

W

e begin at the beginning, at Lake Bennett where the Yukon river rises and where, on a perfect June day in 1898, seven thousand hand-made boats of every conceivable structure and design set off under sail, paddle and sweep for the Klondike goldfields on an adventure which my family and I hope to recapture.

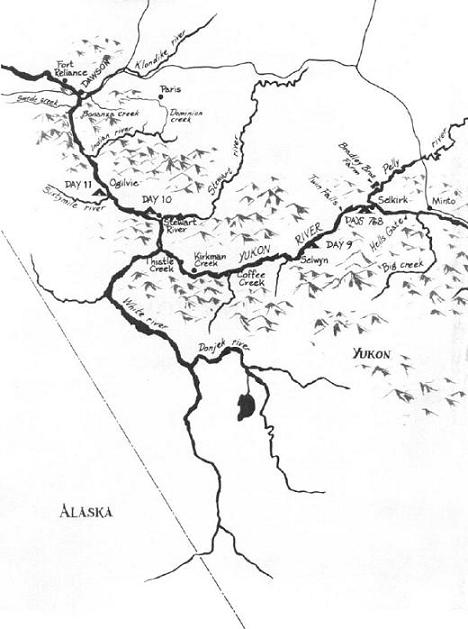

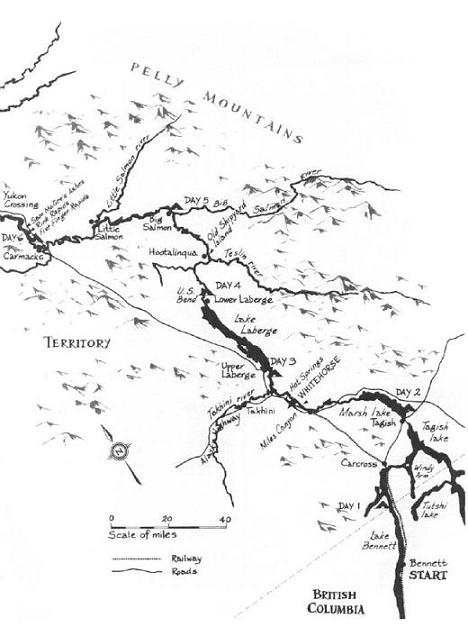

We have come up from Skagway on the Alaskan coast by narrow-gauge railway through the White Pass where the horses died by the thousands and where you can still see the authentic trail of â98, no more than the ghost of a footpath now, hammered into the clay and shale by the tramp of metal shoes and hobnailed boots seventy-four years before. Ahead of us lie six hundred miles of Yukon river system, including four lakes, a canyon, two sets of rapids, sixteen ghost settlements and, at the end of the voyage, my old home town of Dawson. I am going back to my roots; my children are going back with me.

We are standing on the Bennett station platform, looking for our baggage and peering between the coaches out at the choppy lake. I have seen the lake when the wind is asleep and the colour is a brilliant green and the surface so polished that the encircling mountains sweep down to the shoreline to join their mirror image. But now a stiff breeze has darkened the water.

The only visible reminder of the goldrush days is the little church that stands on a promontory at the head of the lake, a simple structure of unpeeled logs, with no floor and scarcely any history because the stampede rolled past it before it could be completed. This deserted log building is probably the most photographed religious structure in Canada: thousands of tourists have taken their cameras to the rocks above the church, carefully placing the spire against the backdrop of lake and mountains. Until today I thought there had never been a service held in the Bennett church. Now, however, a railway official tells my wife, Janet, that there has been a wedding just two days before-a wedding that went on all night, with two hundred guests camped out in the rain to the music of a rock group. “They had to stand up on the train all the way back to Skagway and they was pretty wet from the rain but that music never stopped playing. It was some wedding. You'll never ever see a wedding like it.” The idea of the wedding charms and fascinates Janet; she would like to climb the hill and look over the church but there is no time. She must locate the boxes of provisions we shipped from the East several weeks ago.

There are several hundred people at the Bennett railway station on this August noon hour but only a few are able to see the church or the lake. The station has been cunningly situated so that the tracks lie between the scenery and the lunchroom. Two trains, one from Skagway, Alaska, and the other from Whitehorse, Yukon, effectively block the view. The tourists emerging from lunch must either walk around the trains or clamber illegally between the cars as they unbutton their camera cases and discuss the luncheon they have just finished. Was it moosemeat? they ask themselves. The waitresses have refused to confirm or deny that rumour. So it

must

have been moosemeat!

I have eaten at the Bennett lunchroom more than a dozen times over the past half-century and always there has been this rumour about moosemeat. In fact I used to tell the tourists they were eating moosemeat and half-believed it myself, even though I have eaten enough good moosemeat to know the difference between the real thing and beef cooked black and soaked in gravy. But the rumour persists and the staff encourages it. Why not? It is a harmless fancy.

Far down on the wooden platform, Janet spots a hillock of familiar cardboard boxes and sighs with relief. There are nineteen of them and they represent a triumph of logistics. That pile includes eleven boxes of food, each containing a day's rations and carefully marked from

DAY ONE

to

DAY ELEVEN

in block letters. For weeks, it seems to me, our dining room and kitchen floors were covered with these boxes and their contents as Janet and Pamela, my second daughter, pored over the daily menus and worked and reworked the lists of paraphernalia that would be needed for the trip: cooking utensils, asbestos mitts, tongs, knives, J-cloths, spices, condiments.

“I know we've left something out,” Janet would say in her cheerful manner. “I just

know

it,” and then she would shrug and say “Oh, well, can't be helped” and Pamela, who is so much like her, would shrug with her. “It won't be the end of the world, Mom,” Pamela would say.

Now the two of them walk down the platform to survey the stack of provisions. Much of it has been bruised in three thousand miles of travel. Some of the boxes have been damaged; the string is gone; the cardboard is battered and torn. One or two have sprung open. “It could have been worse,” Janet says. She counts the boxes carefully, checking them against her list. One seems to be lost but neither she nor Pamela can be sure. Did they send an extra box at the last moment? Or was it

two

extra boxes? Those last days became a little hectic. “Oh, well,” Janet says, shrugging once more, “if something goes missing we can always blame it on the lost box.”

In addition to the provisions on the platform, a small mountain of personal luggage-twenty-two separate pieces-has to be hoisted out of the baggage car; when these are stacked next to the nineteen boxes of provisions, they make an awesome pile. How can all this gear and provender -and fourteen people-be packed into three rubber rafts?

That is Skip Burns' problem and he contemplates it with his usual good humour. Skip is the Skagway outfitter who will take us down the river. At the moment, he and his two helpers are pumping up the rafts. He is a lean and raw-boned American in his late twenties, with a Klondike mustache, a shock of red hair, a southern accent, and a brand new bride, Cheri, who works as one of the helpers.

“Congratulations, Skip. When'd you get married?”

“Just two days ago. Right up there.”

“In the church? That was

you

?”

“That was us-it was some wedding. Wasn't it, Cheri?”

Cheri smiles. She is 23, with blue eyes and freckles, and she reminds me of those Yukon saplings that grow along the edges of the creeks; I met her last year when she was working as a packer for Skip on the Chilkoot Pass. While we gasped under our twenty-five pound packs she shouldered sixty and tripped over the mountains like a schoolgirl.

“Going to be a tight fit,” Skip says, as we begin to load the rafts. He has not realized what big eaters we are. He ordinarily supplies the food for his regular river safaris-much of it freeze-dried, light to pack and quick to prepare. But we are a hungry lot and we want to enjoy the meals as well as the scenery, so we have contracted with Skip to supply all that is needed

except

food. Those cartons contain everything from double smoked hams to Ontario cheesesâenough to last at least fourteen people for eleven days-a total of 462 meals. No wonder Skip scratches his head as the rafts sink lower and lower into the water.

“I'm going to have to take on a freight canoe at Whitehorse-that's all there is to it,” Skip tells me. “That means we're going to need an extra pilot.”

The three rubber rafts - I think of them now as boats, for they have high sides and pointed prows-are riding very low. Skip turns to a buddy of his, who has come up on the train with us from Skagway. His name is Ross Miller and he is heading for Atlin where he will join his father, a noted glaciologist, doing experimental summer work on the vast Mendenhall Glacier. When Skip made his first river trip down the Yukon some years ago-a kind of dry run for his outfitting business-Ross was one of a group of Alaskan Boy Scouts he took with him.

Ross is standing off to one side, waiting for the train to move on. He is wearing tweed knickers and low Oxfords, scarcely the proper attire for a river journey. I watch as Skip walks over to him. The two talk together for a few moments, occasionally looking across at us and at the pile of provisions. Then Ross walks over to the baggage car, finds his gear and slings it into one of the boats. He has known us for a few hours only and to him we seem to be pretty much of a closed corporation. But he is an old friend of Skip and Cheri and Skip's other pilot, Scotty Jeffers, and he cannot resist another journey down the river. Now we are fifteen: four guides, two parents, five daughters, two sons, a nephew and a boyfriend. Eight of them share the same grandfather, who, three-quarters of a century ago, at the age of 27, followed this water highway for more than six hundred miles.