Eagles of the Third Reich: Men of the Luftwaffe in WWII (Stackpole Military History Series) (41 page)

Authors: Samuel W. Mitcham

Richthofen became more and more disgusted with Paulus’ leadership as the casualty lists grew. He even went so far as to suggest to Col. Gen. Kurt Zeitzler, the chief of the General Staff of the army, that Paulus and some of his senior commanders be temporarily replaced by more aggressive men, but the suggestion got nowhere.

55

As early as October 1942, aerial photographs by 4th Air Fleet observers convinced Richthofen that the Russians were massing for a major attack against the Rumanians, who were covering Sixth Army’s northwestern flank. Richthofen even dispatched a motorized flak battalion to support them, because they had little in the way of antitank guns. Towards the end of October, Richthofen began to attack Russian troop concentrations opposite the Rumanians. The Russians, however, were past masters at the art of camouflage, and nobody really knew how large their concentrations were. It was clear, however, that the Soviet buildup opposite the Rumanian Third Army had not been detected in its early stages. Increasingly worried, Richthofen ordered General Dessloch to be prepared to launch tactical air sorties in support of the Rumanians on short notice.

56

By early November, Richthofen was openly expressing fear of a massive Soviet counterattack. This fear was shared by Zeitzler, and even Hitler became nervous. On November 12, reconnaissance reports indicated that the Russians were bringing up their heavy artillery opposite the Rumanians: a sure sign of an impending attack. Two days later, the Red Air Force began heavy attacks against German and Rumanian airfields.

57

The Germans’ worst fears were confirmed on November 19, when the Soviet Don and South-West fronts struck the Rumanian Third Army with the Sixty-sixth, Twenty-fourth, Sixty-fifth, 1st Guards, Twenty-first, and Fifth Tank armies, and the 3rd Guards Cavalry and 4th Tank Corps.

58

Except for one brave division, the Rumanians fled in terror. Colonel Rudel, the Stuka pilot, led his group in missions in support of the Rumanians and remembered the scene:

Masses in brown uniforms—are they Russians? No. Rumanians. Some of them are even throwing away their rifles in order to be able to run the faster: a shocking sight . . . [We reach] our allies’ artillery emplacements. The guns are abandoned, not destroyed. We have passed some distance beyond them before we sight the first Soviet troops.

We [the Stuka pilots] find all the Rumanian positions in front of them deserted. We attack with bomb and gun-fire—but how much use is that when there is no resistance on the ground?

We are seized with a blind fury . . . Relentlessly I drop my bombs on the enemy and spray bursts of M.G. fire into these shoreless yellow-green waves of oncoming troops that surge up against us out of Asia and the Mongolian hinterland. I haven’t a bullet left . . .

On the return flight we again observe the fleeing Rumanians; it is a good thing for them I have run out of ammunition to stop this cowardly rout.

59

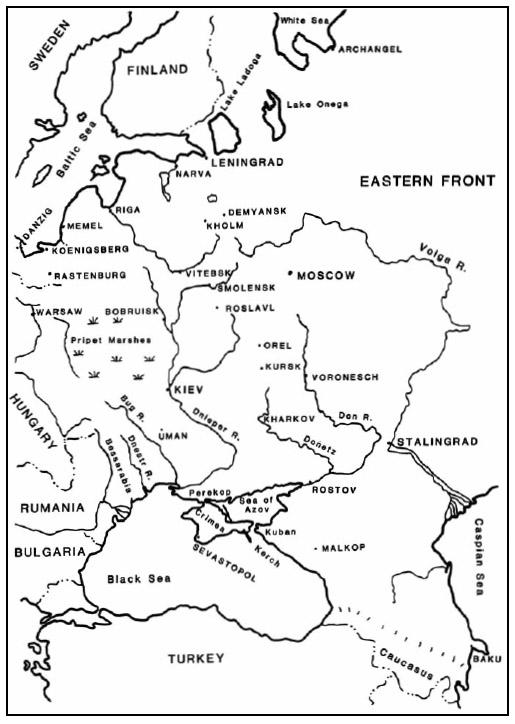

The only German ground unit in the vicinity was Lt. Gen. Ferdinand Heim’s XLVIII Panzer Corps, which consisted of one weak German panzer division and an ill-equipped Rumanian armored division. It, too, was soon in full retreat. Meanwhile, on the southern side of the Sixth Amy, the Stalingrad Front attacked the Rumanian Fourth Army with the Fifty-first, Fifty-seventh, and Sixty-fourth armies, supported by the 4th and 13th Mechanized and 4th Cavalry Corps. The Rumanian Fourth also gave way immediately. Hoth’s Fourth Panzer Army, which had been badly weakened to provide cannon fodder for Paulus in Stalingrad, was unable to halt the Russians and was soon cut in half. By November 20 both Soviet pincers were heading for Kalach, west of Stalingrad. If they reached this position, Sixth Army would be the victim of a double envelopment. Map

7

shows the Stalingrad encirclement.

Richthofen did what he could to halt the Red spearheads, but the weather was so poor that VIII Air Corps could only fly 120 sorties on November 20. After that it was busy evacuating the tactical (dirt surface) airfields between the Don and the Chir. In some cases the last airplanes took off under Russian tank fire. Much of the 2nd Stuka Wing was overrun by Soviet armor and destroyed.

60

Map 7: Eastern Front

Map 7: Eastern Front

Hermann Goering thought he saw an opportunity here to regain some of his lost glory. His influence and standing with the Fuehrer had been deteriorating since the Battle of Britain was lost. Since then two events had accelerated his decline: the 1942 bombings of Germany and the rise of Martin Bormann.

Martin Bormann had replaced Rudolf Hess as chief of the Nazi party in May 1941, after Hess stole an airplane and flew to England, in a vain attempt to make peace with the British. When Hitler asked Goering to recommend a successor, the Luftwaffe C-in-C replied: “Anyone but Bormann.”

61

When Hitler appointed Bormann anyway, Goering was assured of a permanent enemy who would constantly be at the Fuehrer’s elbow.

Bormann was one of the most insidious creatures to come out of the Third Reich. He was brutal, uncouth, unintelligent, unfeeling, and immoral, even to the point of forcing his wife to entertain his mistress. Once a dog became involved in a fight with his mistress’s poodle. Bormann had the animal doused in gasoline and set on fire, and roared with laughter as the helpless animal ran screaming down the street. Bormann, however, possessed a quality Hitler now demanded more and more: he was unquestioningly subservient to the Fuehrer.

With this enemy constantly whispering derogatory comments in Hitler’s ear, Goering’s decline at Fuehrer Headquarters was predictable. The only way the Reichsmarschall could redeem himself in the Fuehrer’s eyes was to score a spectacular military victory. Stalingrad seemed to be his ticket. He promised Hitler that the Luftwaffe would resupply Stalingrad by air.

“Supply an entire army by air?” General Fiebig cried when he received the order on the evening of November 21. “Impossible!”

62

Gen. Kurt Zeitzler, the chief of the General Staff of the army since Halder had been sacked in late September, also thought it was impossible and told Hitler so in no uncertain terms. This lead to a rather heated conference between Goering, Hitler, and Zeitzler, which went like this:

HITLER: “Goering, can you keep the Sixth Army supplied by air?”

GOERING (with solemn confidence): “My Fuehrer! I assure you that the Luftwaffe can keep the Sixth Army supplied.”

ZEITZLER: “The Luftwaffe certainly cannot.”

GOERING (scowling): “You are not in a position to give an opinion on the subject.”

ZEITZLER: “My Fuehrer! May I ask the Reichsmarschall a question?”

HITLER: “Yes, you may.”

ZEITZLER: “Herr Reichsmarschall, do you know what tonnage has to be flown in every day?”

GOERING (embarrassed): “I don’t, but my staff officers do.” Zeitzler stated that the minimum was 300 tons per day. Allowing for bad weather, that meant 500 tons per day was the “irreducible minimum average.”

GOERING: “I can do that.”

ZEITZLER (losing his temper): “My Fuehrer! That is a lie!” An icy silence descended. Zeitzler recalled that Goering was “white with fury.”

HITLER: “The Reichsmarschall has made his report to me, which I have no choice but to believe. I therefore abide by my original decision [not to withdraw from Stalingrad].”

63

Lt. Gen. Hermann Plocher later wrote: “. . . the second man in the nation, whose prestige in the eyes of the Fuehrer had been steadily declining, might have wished to reestablish himself with Hitler by making him an unqualified promise.”

64

It was the major turning point of the war.

Goering again mortgaged the future by sending school cadres and training aircraft to the Stalingrad sector and by using He-111 bombers as supply carriers in this emergency, but this time to no avail. On December 21, when the situation at Stalingrad was rapidly deteriorating and disaster seemed inevitable, Field Marshal Kesselring visited Fuehrer Headquarters at Rastenburg, East Prussia, on an unrelated manner. He paid a call on Goering, but was met at the door by General Bodenschatz, who asked him what he wanted. Kesselring looked over Bodenschatz’ shoulder and could see Goering, who was sobbing aloud, his head on his writing desk.

Richthofen, whose 4th Air Fleet would be responsible for the airlift, considered the prospect of resupplying Sixth Army from the air to be impossible from the first. On November 21, two days before the encirclement was completed, he told Manstein that it was an impossible task. He sent similar messages to Goering and Zeitzler. He telephoned Jeschonnek and screamed at him: “You’ve got to stop it [the airlift]! In this miserable weather there’s no way to supply an army of 250,000 men from the air. It’s madness!”

65

His assessment of the situation, however, was ignored at both Luftwaffe and Fuehrer Headquarters, except by Colonel General Jeschonnek.

66

The chief of the General Staff of the Luftwaffe always listened to Richthofen—indeed was too much under his influence, according to some critics—and on the twenty-second reversed his original stand and called for Sixth Army to break out.

67

Like Richthofen and Zeitzler, he was ignored by Goering and Hitler.

On the morning of November 24, Hitler dispatched his famous order commanding Sixth Army to stay where it was. No breakout would be allowed. The next day, Richthofen telephoned Goering (then in Paris) and urged him to use his influence with Hitler to allow the Sixth Army to break out to the southwest. Goering would do nothing, however, and Hitler refused to reconsider his decision, because he did not believe the Wehrmacht would ever reach Stalingrad again if he withdrew now.

68

Once the decision to hold Stalingrad was made, General von Richthofen accepted it and did his best to aid the beleaguered garrison. “We have only one chance to cling to,” he said. “So far the Fuehrer has always been right, even when none of us could understand his actions and most of us strongly advised against them.”

69

He began assembling his units as quickly as the Russian winter would allow, even though he considered the operation futile from the start.

Colonel General Paulus and his strong-willed chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Arthur Schmidt, were demanding 750 tons of supplies per day, a figure that was later reduced to 500 per day. Fourth Air Fleet never came close to reaching this daily goal. Initially, Richthofen had the following forces available for air transport duties:

900th Special Purposes Bomber Wing

172d Special Purposes Bomber Wing

50th Special Purposes Bomber Wing

102d Special Purposes Bomber Wing

5th Special Purposes Bomber Wing

55th Bomber Wing

27th Bomber Wing

HQ, 1st Special Purposes Bomber Wing

III Group, 4th Bomber Wing

70

These units had all been in more or less continuous action since summer and were worn out. Operational readiness stood at about 40 percent in the

Geschwadern

.

71

In addition, the ground and supply organizations were totally inadequate for a resupply effort of the magnitude Hitler demanded.

Col. Fritz Morzik, the chief of the Luftwaffe Air Transport Branch, calculated that it would take 1,050 Ju-52s to meet Sixth Army’s demands, based on an operational readiness of 30 percent to 35 percent and a two-ton payload per aircraft. At that time there were only about 750 Ju-52s in the entire Luftwaffe, which was also engaged in a desperate effort to resupply the XC Army Corps in Tunisia and Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Panzer Army Afrika, then retreating across Libya after its decisive defeat at El Alamein. Goering reacted to the situation in his typical manner: he stripped the Training Command of 600 aircraft, plus its best instructor pilots and crewmen. He-111 bombers, which could deliver one and a half tons of supplies, were converted into emergency air transporters and were rushed to southern Russia. Ju-90, Ju290, and FW-200 “Condor” long-range reconnaissance aircraft, Ju-86 trainers, and even untried and experimental He-177 long-range bombers were forced into emergency transport duties.

72

All totalled, Richthofen had 500 transports (including converted bombers) by early December, when his operational strength was approximately at its highest. General Fiebig was named chief air supply officer, Stalingrad, and Col. Hans Foerster, the commander of the 1st Special Purposes Bomber Wing, took command of the air transport units. (Foerster was later replaced by Colonel Morzik.) After several days’ delay due to bad weather, Foerster assembled the bulk of his units at Tatsinskaya Airfield, and the airlift began. Meanwhile, Sixth Army was already eating its horses, which meant that most of the divisions could not move their artillery and divisional trains, even if the breakout order came. Table

14

shows the order of battle of the air transport command, 4th Air Fleet, in early December 1942, and indicates the units which arrived after the encirclement of Stalingrad. Many of these units had been recently formed, and their pilots and crews were inexperienced at operating in the Russian winter.

73