Enemy on the Euphrates (9 page)

Read Enemy on the Euphrates Online

Authors: Ian Rutledge

1) Retain complete control of the lower portion of Mesopotamia comprising the Basra Vilayet and including all outlets to the sea and such portions of neighbouring territories as may affect your operations.

2) Without prejudicing your main operations, endeavour to secure the safety of the oilfields, pipelines and refineries of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company.

3) Submit plans for the effective occupation of Basra Wilaya and a subsequent advance on Baghdad.

5

So although some part of the original objectives of the invasion remained (protecting the oil facilities), there were now clear indications that a more ambitious campaign was contemplated – today we would call it ‘mission creep’. Occupying the whole of the Basra vilayet would mean advancing further up the Tigris, and although only a ‘plan’ for an advance to Baghdad was requested, the general impression given by High Command was that orders for such an advance would not be long in following. Indeed, both General Nixon and Sir Percy Cox openly advocated such an attack.

Cox had been urging an advance as far as Baghdad since the initial invasion. On 23 November 1914, the day after the capture of Basra, he had privately telegraphed the Viceroy of India, Lord Hardinge, that he did not see how ‘we can well avoid taking over Baghdad’. His telegram was prompted – as he later admitted – by ‘urgent representations from the Heads of the British Mercantile community’.

6

One ‘Head’ appears to have been particularly vociferous in this respect. A month later, the redoubtable Lord Inchcape, someone with substantial commercial interests in the Gulf ranging from shipping to oil, wrote to Sir Edward Grey, the foreign secretary, urging an advance on Baghdad as soon as practicable, and went on to say:

Now is our chance to get hold of the Baghdad-Basra section of the Baghdad railway, to permanently secure our position in the Persian Gulf, that highway to India … British and Indian trades are greatly interested in Mesopotamia and there are enormous developments possible there if the country is properly and honestly administered.

7

However, in the meantime, more urgent considerations engaged the new British commander-in-chief. In spite of the fact that his wounds had not yet healed, the new Turkish commander, Lieutenant Colonel Sulayman al-‘Askari, had decided to return to the front.

The British had established a forward defensive position around the town of Shu’ayba, about fourteen miles south-west of Basra on a ridge facing towards the desert, manned by five British and Indian infantry battalions, a battery of Royal Field Artillery and some Indian cavalry; but much of the area between Shu’ayba and Basra which had been inundated was still under water and reinforcements could reach the British forward position across the marshes only via a precarious raised causeway or by bellums, a few men at a time.

Realising that the British position at Shu’ayba was virtually cut off from their remaining forces around Basra, Colonel al-‘Askari decided to attack and destroy it while it remained isolated. So, carried on a litter because of his wounds, the Turkish commander and his men made a forced march down the right bank of the Euphrates,

eventually joining up with the army of mujahidin at Nukhayla on 10 April.

8

The battle of Shu’ayba is probably the least-known battle in the least-known theatre of the First World War; but it was significant for two reasons: firstly, the strategic one – because if the British had lost, Basra would almost certainly have fallen, and with it their whole bridgehead in Iraq – and secondly, while it is customary in the few military accounts of the battle to refer to the enemy as ‘Turks’, in fact the majority of combatants on the Ottoman side at Shu’ayba, probably around 17,000, were irregular Arab tribesmen, while the regular Ottoman troops, of whom only half were Anatolian Turks, numbered between 6,000 and 7,000.

9

The mujahidin from the middle and southern Euphrates, who had flocked to the Ottoman colours earlier in the year and were now brimming with confidence and martial fervour, were at last about to confront the invading infidels.

Probing attacks by Turkish and Arab troops began on 11 April and were held off without great difficulty until nightfall, but it was reported to Major General Charles Mellis, the most senior British officer at the front, that the Ottoman troops around Shu’ayba were increasing by the hour and that a major offensive was threatened. The following morning, Mellis, who until then had been stuck on the eastern side of the flooded area, was able to cross over to Shu’ayba with his HQ and a battalion of his 30th Infantry Brigade in a fleet of bellums, followed by the remainder of the brigade and a battery of mountain guns.

Many years later, in his memoirs, Sayyid Muhsin Abu Tabikh, a commander of the mid-Euphrates tribesmen and one of the leaders of the great anti-British uprising of 1920, gave the following account of the Ottoman débâcle at Shu’ayba. Having explained that their regular troops were deployed in the centre, he went on to describe the tribal deployment and the ensuing battle.

Our right flank was composed of tribesmen from the Basra region together with a section of tribes from the Muntafiq, at the head of which was ‘Ajaimi Sa‘dun Pasha. The left flank was made up of the

remainder of the Muntafiq tribesmen and tribes from the mid-Euphrates and other regions, under the command of ‘Abdallah Sa‘dun Bey. At dawn on the 12 April, Sulayman al-‘Askari ordered an all-out attack which lasted until the forenoon. The English then directed their artillery fire at our right wing and launched a counter-attack. They inflicted heavy losses upon it and forced it back to the point where its advance had begun. Then they focussed their attack upon our left flank and I myself was wounded in the forehead by a shrapnel splinter. All this occurred during the first hour of the battle and I left the battlefield as we were all forced to retreat, leaving behind the dead and all the wounded who could not be moved, including one of my cousins, Sayyid Radi Abu Tabikh … With the retreat of the mujahidin, our left wing scattered and it played no further part in the battle leaving the English to concentrate their fire upon the Ottoman regular troops who were engaged with heavy artillery and some lighter armed troops. The English charged towards the Ottoman troops in a counter-attack with all their men, compelling them to retreat, inflicting heavy losses upon them … And when news of the rout of the Ottoman troops reached the Commander in Chief, Sulayman ‘Askari Bey, whose HQ was situated in the Barjishiya woods together with his general staff, he chose death rather than life.

10

Gathering the remainder of his officers around him, the despairing Lieutenant Colonel al-‘Askari drew his pistol and blew his brains out, after which the remains of the Ottoman army and tribal mujahidin streamed back to Nasiriyya in complete disorder, some of the Arabs even pillaging the baggage and rifles of the fleeing Turkish regulars.

Much has been made of the fact that after their initial encounter with the British, the tribal mujahidin played no further part in the battle of Shu’ayba.

11

Later, they were even accused of treachery by the Turks. But it is not difficult to understand their reluctance to re-engage in the fighting after their first, doomed assault. The Ottoman losses at Shu’ayba amounted to around 3,000 dead and wounded,

12

but probably the majority of these were Arab tribesmen, cut down within the first hour of fighting in their near-suicidal frontal assault.

13

The tribesmen had absolutely no experience of modern warfare – only sporadic tribal raiding in which casualties were typically very low. At best, the

mujahidin would have been armed with elderly Martini-Henry rifles and in all probability many carried nothing more than a lance or spear. They stood little chance against a modern army with modern weapons and their reluctance to renew their attack is understandable.

Pacifying Arabistan

If General Nixon was going to protect not only the 138-mile pipeline to Abadan but the Persian oilfield itself, he was also going to have to send more troops up the Karun river into south-west Persia. This was fast becoming a matter of some urgency. Telegrams from the India Office had informed Nixon that the Admiralty were getting worried. Rapid repair of the pipeline was essential. ‘The oil question is becoming serious,’ they complained.

1

After the victory at Shu’ayba, General Nixon was able to detach a division-sized force under the command of Major General George Gorringe to cross into Persian Arabistan to avenge the defeat of their earlier incursion, conduct a large-scale pacification campaign against the tribes and ensure the permanent safety of Britain’s Persian oilfield. Lieutenant Wilson was attached to the force as a political officer (PO).

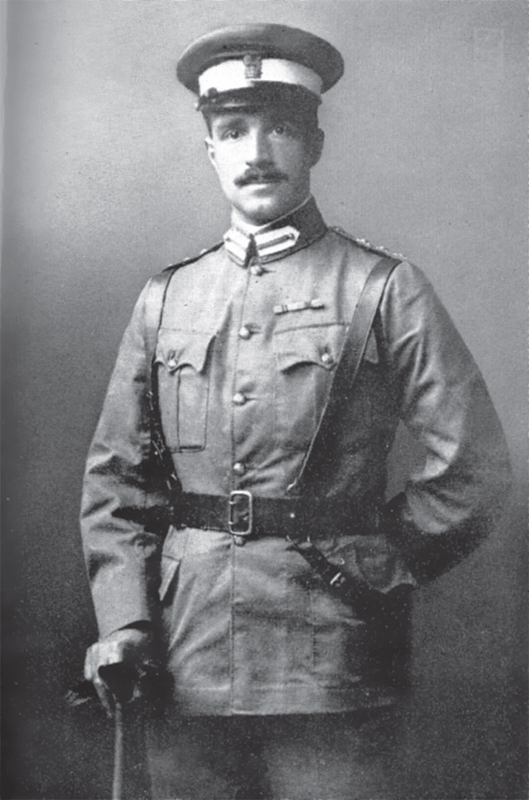

Let us picture Lieutenant Wilson as he presents himself for duty. He is now thirty-one years old, of above average height, broad shouldered and still sunburned even after some weeks in cloudy England. His moustache is thick but neatly trimmed, his eyes dark and commanding; above them, beetling black eyebrows and close-cropped hair. He wears the old-fashioned Indian Army tunic with a high collar buttoned to the neck, eschewing the new-fangled collar and tie which even his superior, Sir Percy Cox, has now adopted. Equally and characteristically conservative is his sidearm belt with two parallel shoulder straps instead of the now more customary Sam Browne, and holstered on his left hip is his service revolver. Round the brim of his cap is a white band and on his collar the two white chevrons indicating unmistakably that he is an officer of the Indian Political Service.

Captain Arnold Wilson in the uniform of a Political Officer of the Imperial Indian Army, 1916

Over the past few years Wilson’s social and political views have become more aligned with his sartorial conservatism. As he has matured in age, his opinions have narrowed and hardened. In a letter to his parents he states, ‘The more I see of eastern races and western races in the East the more I feel that racial differences are deep and ineradicable … Education makes the points of difference sharper and harder to conceal.’

2

He disagrees profoundly with the views of those he refers to as ‘Liberals’, like the orientalist Professor E.G. Browne, who believe that democratic constitutional self-government should be the objective of British policy in the East. Indeed, he is equally antipathetic to the progress of democracy and social justice in Britain, attacking the extension of the suffrage to women, co-education, redistributive taxation, state old age pensions and trade unions. ‘Radicalism’, he pronounces, ‘is the creed of the half-educated,’ adding rather ominously, ‘We want Order and Law, not Law and Order.’ And now he is about to have his first experience of large-scale military action.

Major General Gorringe had made sure that his force was certainly not going to suffer the indignity that had befallen the earlier column that had entered Persian Arabistan, and his force therefore consisted of six squadrons of cavalry, seventeen guns, six infantry battalions and a bridging train. Its supplies were carried by some 900 mules supplied by the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. ‘A sledgehammer to crack a nut,’ thought Wilson.

By chance, Wilson was familiar with the marshy territory between the Karun and Karkha rivers into which the troops were now advancing. He had reconnoitred the area in 1911 and early 1914 when mapping the border for the commission which was attempting to delineate the boundary between Ottoman Iraq and Persia. That task had become essential to the interests of Anglo-Persian, whose vast concession covered territory straddling the previously undefined boundary. Only when the frontier had been finally settled and agreed between the Ottoman and Persian governments would it be possible for Anglo-Persian to sign contracts with the relevant authorities and begin further oil-exploration

operations in the disputed region. Just before the outbreak of hostilities, the Turks had given assurances that any oil discoveries ‘moving’ from Persian territory to Ottoman Iraq as result of the boundary changes would continue to belong to the Anglo-Persian Oil Company.

On that earlier journey in Persian Arabistan, in January 1914, Wilson and the other members of the Border Commission had travelled along the edge of the vast Karkha marshes, passing through villages precariously protected from inundation by small mud ledges, barely sufficient to keep out the waters fed by the melting snows of Luristan’s distant mountains. For parts of the journey they travelled in a mashuf, the typical light marsh boat of the region with a long projecting prow, cautiously paddling their way between dense thickets of mardi reeds as tall as a house. Eventually they had arrived at Khafajiyya, the principal village of the Bani Turuf.

On arrival at Khafajiyya’s collection of reed-built houses they were warmly received. The two leading sheikhs of the Bani Turuf, Sheikh ‘Asi and Sheikh ‘Aufi, offered coffee to Wilson and his companions, served to them by ‘Asi’s qahwaji, his coffee-maker and chief attendant, and they provided Wilson with useful information in furtherance of his map work. Later, after they had left Khafajiyya and journeyed to Bisaitin, another village of the Marsh Arabs, they encountered a party of 150 Bani Turuf who had apparently been sent out to protect them from Bani Lam raiders active in the area. The Bani Turuf tribesmen had made a fine display, carrying rifles, swords and fishing tridents as weapons, and they held aloft their tribal standards, one of which was a fine piece of salmonpink satin eight feet square with green edges, carrying in the centre the crescent of Islam and a single star. ‘Fine-looking men,’ Wilson thought.