Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (100 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

1.

subacute combined degeneration of the cord (vitamin B

12

deficiency)

2.

conus medullaris lesion

3.

combination of an upper motor neurone lesion with cauda equina compression or peripheral neuropathy

4.

syphilis (tabo-paresis)

5.

Friedreich’s ataxia

6.

diabetes mellitus (uncommon)

7.

adrenoleucodystrophy or metachromatic leucodystrophy.

BROWN-SÉQUARD SYNDROME (HEMISECTION OF THE SPINAL CORD)

Clinical features

1.

Motor changes:

a.

upper motor neurone signs below the hemisection on the

same

side as the lesion

b.

lower motor neurone signs at the level of the hemisection on the

same

side.

2.

Sensory changes:

a.

pain and temperature loss on the

opposite

side of the lesion (

note:

the upper level of sensory loss is usually a few segments below the level of the lesion)

b.

vibration and proprioception loss on the

same

side

c.

light touch is often normal

d.

there may be a band of sensory loss on the same side at the level of the lesion (afferent nerve fibres).

Common causes

1.

Multiple sclerosis.

2.

Angioma.

3.

Glioma.

4.

Trauma.

5.

Myelitis.

6.

Postradiation myelopathy.

CAUSES OF DISSOCIATED SENSORY LOSS (USUALLY INDICATES SPINAL CORD DISEASE, BUT MAY OCCUR WITH PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHY)

Spinothalamic (pain and temperature) loss only

1.

Syringomyelia (‘cape’ distribution).

2.

Brown-Séquard syndrome (contralateral leg).

3.

Anterior spinal artery thrombosis.

4.

Lateral medullary syndrome (contralateral to the other signs).

5.

Peripheral neuropathy (e.g. diabetes mellitus, amyloid, Fabry’s disease).

Dorsal column (vibration and proprioception) loss only

1.

Subacute combined degeneration.

2.

Brown-Séquard syndrome (ipsilateral leg).

3.

Spinocerebellar degeneration (e.g. Friedreich’s ataxia).

4.

Multiple sclerosis.

5.

Tabes dorsalis.

6.

Sensory neuropathy or ganglionopathy (e.g. carcinoma).

7.

Peripheral neuropathy from diabetes mellitus or hypothyroidism.

SYRINGOMYELIA (A CENTRAL CAVITY IN THE SPINAL CORD)

Clinical triad

1.

Loss of pain and temperature over the neck, shoulders and arms (‘cape’ distribution).

2.

Amyotrophy (weakness, atrophy and areflexia) of the arms.

3.

Upper motor neurone signs in the lower limbs.

Note:

There may also be thoracic scoliosis owing to asymmetrical weakness of the paravertebral muscles.

An approach to myopathy

CAUSES OF PROXIMAL MUSCLE WEAKNESS

1.

Myopathic (see below).

2.

Neuromuscular junction disorder – myasthenia gravis.

3.

Neurogenic – Kugelberg-Welander disease (proximal muscle wasting and fasciculation as a result of anterior horn cell damage – autosomal recessive), motor neurone disease, polyradiculopathy.

CAUSES OF MYOPATHY

1.

Hereditary muscular dystrophy (qv).

2.

Congenital myopathies (rare).

3.

Acquired (mnemonic PACE PODS):

P

olymyositis or dermatomyositis (

Figs 16.100

and

16.101

)

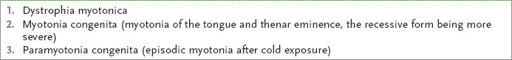

FIGURE 16.100

Dermatomyositis. Gottron’s papules consisting of purplish-red, slightly scaling plaques on the extensor surfaces of the finger joints and knees. H B Pride.

Pediatric dermatology

, 1st edn. Fig. 12-5. Saunders, Elsevier, 2008, with permission.

FIGURE 16.101

Heliotrope rash in a patient with dermatomyositis. W D James et al.

Andrews’ diseases of the skin: clinical dermatology

, 11th edn. Fig 8-15. Saunders, Elsevier, 2011, with permission.

A

lcohol

C

arcinoma

E

ndocrine (e.g. hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, Cushing’s syndrome,

acromegaly, hypopituitarism)

P

eriodic paralysis (hyperkalaemic or hypokalaemic or normokalaemic)

O

steomalacia

D

rugs (e.g. clofibrate, chloroquine, steroids)

S

arcoidosis

Note:

Causes of proximal myopathy and a peripheral neuropathy include:

1.

paraneoplastic syndrome

2.

alcohol

3.

connective tissue disease.

MUSCULAR DYSTROPHIES

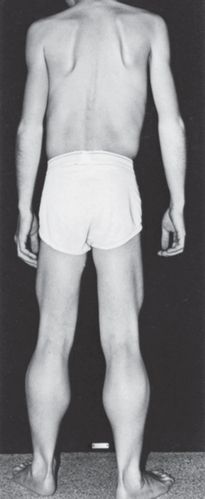

1.

Duchenne’s (pseudohypertrophic) (sex-linked recessive disorder) (

Fig 16.102

):

FIGURE 16.102

Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy. R B Daroff.

Bradley’s neurology in clinical practice

, 6th edn. Fig 79.9. Saunders, Elsevier, 2010, with permission.

a.

affects only males (or females with Turner’s syndrome) (

Fig 16.103a and b

)

FIGURE 16.103

(a) and (b) Muscular dystrophy facies. V Laina, A Orlando. Bilateral facial palsy and oral incompetence due to muscular dystrophy treated with a palmaris longus tendon graft.

Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery

, 2008. Figs 2a and b.

b.

the calves and deltoids are hypertrophied early and weak later

c.

early proximal weakness

d.

tendon reflexes are preserved in proportion to muscle strength

e.

severe progressive kyphoscoliosis

f.

heart disease (dilated cardiomyopathy)

g.

creatine kinase level markedly elevated

h.

patients die in the second decade, usually from heart disease.

2.

Becker (sex-linked recessive disorder): same features as Duchenne’s, but less severe, has a later onset and is less rapidly progressive.

3.

Limb girdle (autosomal recessive):

a.

shoulder or pelvic girdle affected (onset third decade)

b.

face and heart usually spared.

4.

Facioscapulohumeral (autosomal dominant): facial and pectoral girdle weakness with hypertrophy of the deltoids (normal pelvic muscles early).

5.

Distal dystrophies:

a.

autosomal dominant disease, which is rare and causes distal muscle atrophy and weakness

b.

dystrophia myotonica (autosomal dominant).

TESTS FOR MYOPATHY

1.

Creatine kinase (highest in Duchenne’s).

2.

EMG.

3.

ECG (particularly Duchenne’s and dystrophia myotonica).

4.

Muscle biopsy.

Dystrophia myotonica

‘This 67-year-old man has noticed some arm weakness. Please examine him.’

Method

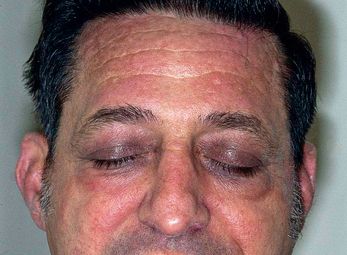

Standing back to observe the patient, you fortunately notice the features of myotonic dystrophy (

Fig 16.104

). Proceed as follows.

FIGURE 16.104

Dystrophia myotonica with frontal balding and bilateral ptosis. G Douglas. The general examination.

Macleod’s clinical examination

, 3rd edn. Fig. 3.11. 41–62. Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier, 2013, with permission.

1.

Observe the face for frontal baldness (the patient may be wearing a wig), dull triangular facies (‘hatchet’ face), temporalis, masseter and sternomastoid atrophy, and partial ptosis. Note thick spectacles, as these patients develop cataracts and fine subcapsular deposits, which are virtually diagnostic.

2.

Look at the neck for sternomastoid atrophy, then test neck flexion (neck flexion is weak, while extension is normal).

3.

Go to the upper limbs. Shake hands (for grip myotonia) and test percussion myotonia. Tapping over the thenar eminence causes contraction then slow relaxation of the abductor pollicis brevis (see

Table 16.56

).

Table 16.56

Causes of myotonia