Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (62 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

2.

volume overload despite salt and water restriction and diuretic use

3.

hyperkalaemia unresponsive to conservative measures

4.

progressive deterioration of renal function (dialyse before symptoms develop)

5.

acute renal failure (dialyse early).

Note:

Dialysis may be started earlier to avoid these complications.

Renal transplantation

Renal transplantation is now a widely accepted, commonly performed treatment for end-stage renal failure. Unfortunately patients continue to have a number of chronic problems that may bring them into hospital and make them available for examinations. Cadaveric transplantation is generally more common than the use of matched family donors. Specific contraindications to renal transplantation include recent malignancy, an untreatable focus of infection and severe external disease.

The prognosis continues to improve and the introduction of cyclosporin and other immunosuppressives has made a substantial difference to survival rates. The 1-year graft survival rate is now more than 90% in experienced centres. The selection of patients for transplant is difficult. Shortages of donor organs mean that transplant is not offered to elderly patients, those with other serious illnesses or those with unrevascularised coronary artery disease.

The history

1.

Ask the patient about the cause of the original renal failure. Find out how long the transplant has been in situ and whether this is the patient’s first transplant. Ask whether the kidney came from a relative or was a cadaveric graft.

2.

The patient should be well informed about previous rejection episodes and how these have been managed. Find out whether this is the reason for the current admission. Clinically, rejection may be marked by fever, swelling and tenderness over the graft. The patient should be aware of all these signs. There is also often a reduction in urine volume. A rise in creatinine level is usual. Ask about recent graft biopsies, which may have been necessary to assess rejection, recurrence of disease or drug toxicity.

3.

Find out what immunosuppressive drugs the patient is taking and in what doses. He or she should know whether changes in doses have been required recently because of problems with any of the drugs.

4.

Ask about specific complications of immunosuppression.

a.

Cyclosporin can result in significant side-effects. The drug can be associated with an increase in hirsutism, tremor, gout, renal impairment, increased liver function tests (especially bilirubin), hypertension, hyperkalaemia, hypomagnesaemia, gingival hypertrophy and rarely haematological malignancy.

b.

Mycophenalate is associated with an increased risk of infections and leukopenia.

c.

The mTOR inhibitors sirolimus and everolimus are associated with proteinuria, hyperlipidaemia, pneumonitis, tendon rupture and slow wound healing. They may need to be stopped temporarily before and after surgery.

d.

Ask about ischaemic heart disease and peripheral vascular disease, infections and malignancy, as the incidence of these conditions remains higher than in the general population.

The examination

1.

Look particularly at the skin for squamous and basal cell carcinomas.

2.

Note any signs of Cushing’s syndrome and hirsutism (e.g. cyclosporin).

3.

Examine the abdomen carefully, noting the position and site of the allograft and whether it has any tenderness or bruits.

4.

Look for old vascular access sites for haemodialysis and decide whether there will be problems finding sites for access for further dialysis if this is required.

5.

Examine the lungs for signs of infection and the mouth for

Candida

. Inspect the gums. Note gouty tophi. Look at the temperature chart.

Investigations

1.

It is important to obtain the serum creatinine level and, if possible, establish whether the serum creatinine level has been rising or falling since the time of transplantation. A slightly elevated creatinine level is considered acceptable in patients on cyclosporin treatment as this drug interferes with renal function. Patients usually know their creatinine and eGFR results. If they don’t, there may be some doubt about their compliance with treatment and understanding of their disease.

2.

The electrolyte levels and liver function test results are important. Cyclosporin can cause hepatotoxicity and renal impairment, as can cytomegalovirus infection of the liver.

3.

A white cell count should be obtained to look for leucocytosis (infection or steroids) and leucopenia (e.g. excessive doses of azathioprine). The azathioprine dose is usually adjusted according to the neutrophil count. The haemoglobin is usually normal in patients with a successful transplant and good function.

4.

The results of blood cultures should be sought if there has been any suggestion of recent infection. Urinary tract infection must also be considered and early urine microscopy is helpful.

5.

Exclude prerenal and postrenal disease. A renal scan and ultrasound with measurement by Doppler is useful for estimating renal artery blood flow.

Management

1.

The majority of patients receiving chronic dialysis are candidates for renal transplantation (

Table 11.8

). The donor’s kidneys should be ABO-compatible. Typing by human leucocyte antigens (HLA) -A, -B and -DR improves graft survival. Three HLA antigens are inherited from each parent. A complete match is for six antigens. The graft survival rate for these patients is 50% at 20 years. The long-term graft survival rate declines with a decrease in the number of matches. The recipient is usually screened for antibodies to class 1 antigens (HLA-A and -B) before receiving the transplant, as their presence is associated with hyperacute rejection.

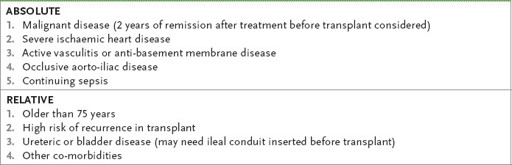

Table 11.8

Contraindications to renal transplant

2.

Management problems include acute tubular necrosis, infection, cyclosporin nephrotoxicity (acute vasoconstriction, haemolytic uraemic syndrome or dose-related nephrotoxicity) rejection episodes, disease recurrence and chronic allograft nephropathy.

3.

Rejection is prevented by the use of steroids, mycophenolate and calcineurin inhibitors (usually tacrolimus 100–150 mg twice daily) or mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) inhibitors (everolimus and sirolimus).

a.

Mycophenalate

can be used with allopurinol, can cause leukopenia, its dose is 500 mg–1000 mg twice daily.

b.

Tacrolimus

is a calcinerurin inhibitor. Trough levels should be monitored (5–10 ng/mL). It can cause renal dysfunction, alopecia and hypertension but (unlike cyclosporin) not gout, hirsutism or gum changes.

c.

Sirolimus

and

Everolimus

are mTOR inhibitors, given daily orally. Their adverse effects include a reduced white cell count (use with caution in combination with mycophenalate), increased lipids and proteinuria. Monitor trough levels. They delay wound healing and should be replaced before surgery with tacrolimus and restarted 1–3 months later.

Acute rejection episodes are treated with three pulse doses of 0.5–1 g intravenous methylprednisolone or monoclonal antibody (e.g. muromonab–CD3) if the episode is resistant to steroids. Azathioprine is given in doses of 1.5–3 mg/kg/day; it is metabolised by the liver so its dose does not need to be varied according to renal

function, but the dose is usually adjusted according to the neutrophil count. The use of allopurinol should be avoided because it interferes with azathioprine excretion and increases bone marrow toxicity.

Azathioprine

has largely been replaced by mycophenalate (resulting in less acute rejection), but some patients with older transplants may still be taking azathioprine.

Prednisone is given in maintenance doses of approximately 7.5–10 mg daily after about 6 months. A gradually rising creatinine level may be a sign of cyclosporin toxicity (which, if caused by interstitial fibrosis, is not reversible) or of chronic rejection. This is a difficult clinical problem, but graft biopsy can be used to decide whether the cyclosporin should be stopped or immunosuppression increased.

4.

Opportunistic infections typically occur a month or more post-transplant.

Toxoplasma

,

Nocardia

and

Aspergillus

are now less common with current immunosuppressive protocols; viral infections (especially CMV) dominate. Infection must be aggressively diagnosed (e.g. by blood cultures and lung biopsy) and treated. When infections are life-threatening, immunosuppressive treatment, apart from prednisone, should be suspended. CMV prophylaxis with ganciclovir and PCP prohylaxis with co-trimoxazole may be indicated.

5.

The major cause of graft loss is chronic rejection (chronic allograft nephropathy).

6.

Recurrence of glomerulonephritis in the transplanted kidney is not uncommon but is an uncommon cause of loss of the transplant. It is most common with focal glomerulosclerosis. IgA nephropathy, Goodpasture’s syndrome but membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (especially type II) can also recur.

7.

Some diabetic patients with end stage renal failure will have undergone kidney/pancreas transplants. They may have the additional problems with pancreatic drainage (bladder or to gut) and leakage.

CHAPTER 12

The neurological long case

The brain is a wonderful organ. It starts working the moment you get up in the morning and does not stop until you get into the office.

Robert Frost (1874–1963)

Multiple sclerosis

This is a common chronic disease. Patients suffering from multiple sclerosis (MS) are readily available for the clinical examinations. They are mostly very well informed about, and interested in, their disease. MS usually begins in early adult life and is more common in women (2:1). The disease is much more common among people who lived as children in regions far from the equator. Exposure to Epstein-Barr virus infection at an older age increases risk and the condition is rare in sero-negative individuals. Numerous alleles associated with risk have been identified, but HLA-DRB1 has the strongest association.

The most common pattern of disease is called

relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis

(RRMS). In untreated patients the rate of relapse is 0.65 attacks a year. Episodes of fever or fatigue associated with a temporary worsening of symptoms are not considered to be relapses and are called

pseudorelapses.

In most cases complete or almost complete resolution of symptoms occurs in this phase of the disease. After 10 years up to 50% of patients begin to develop a progressive accumulation of disability –

secondary progressive MS

(SPMS). Eventually 80% of patients enter this stage.

The history

The disease usually begins with an episode of acute neurological disturbance, which is called a

clinically isolated

syndrome. However, the clinical diagnosis requires at least two neurological events separated in time and place within the central nervous system (CNS). MS is primarily a clinical diagnosis, but the use of MRI scanning has led to the McDonald criteria for diagnosis. These allow for the diagnosis after a single neurological episode if the MRI shows a separate area typical of MS (see

Table 12.1

).

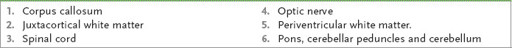

Table 12.1

Sites of demyelinating lesions on MRI scanning

1.

Ask about the presenting symptoms (listed here in approximate order of importance):

a.

episodes of spastic paraparesis, hemiparesis or tetraparesis (may present as gradually progressive disease in late-onset MS)

b.

episodes of limb paraesthesiae (owing to posterior column, medial lemniscus or internal capsule involvement)