Folklore of Yorkshire (19 page)

Read Folklore of Yorkshire Online

Authors: Kai Roberts

Yet, whilst this story indicates that, should a family wish to rid themselves of their hob or boggart, all that was required was to leave it a gift of clothes, a seemingly contradictory strand of the household spirit tradition suggests that an unwanted hob or boggart was almost impossible to dislodge. Unlike the blameless Hob of Hart Hall, many such beings had a dual aspect which ranged from trivial acts of mischief to outright malice. It seems that household spirits were particularly sensitive creatures and would take offence at a variety of perceived slights, such as general mockery, criticism of its work, interference with its movements, failure to leave a bowl of milk for it to drink or spying on its labours. Some writers have suggested that when a hob was angered it

became

a boggart, and it is true that ‘boggart’ seems to be applied to mischievous household spirits more often than helpful ones, but in other cases the terms are used inconsistently or interchangeably.

In some instances, such as at Spaldington Hall in the East Riding, the boggart’s shenanigans would be little more than a harmless irritation. Robin Round-Cap – as this example was known – gained fame for ‘remixing the winnowed wheat with the chaff ... putting out the fire ... kicking over the milk-pail.’ In this respect, he seems to have acted as a scapegoat for all the minor irritations of daily life, not to mention a phenomenon on to which clumsy and lazy servants could deflect blame for their lapses. In other cases, however, the spirit’s devilry was more pronounced and less explicable. Katharine Briggs writes, ‘The traditional behaviour of boggarts and mischievous hobgoblins is indistinguishable from what psychical researchers call “poltergeist manifestations” ... The phenomena are fairly constant. There is always knocking, almost always the throwing of stones and pebbles, over-setting of dishes, sometimes throwing of fire [and] clattering of china.’

On other occasions, the boggart became a great deal more violent. A story collected from a Yorkshire tailor in the 1750s relates,

The children’s bread and butter would be snatched away, or their porringers of bread and milk would be dashed down by an invisible hand … One day the farmer’s youngest boy was playing with the shoe-horn and as children will do he stuck the horn in a knot-hole … The horn darted out with velocity and struck the poor child over the head.

Meanwhile, a story recorded around Whitby in 1828 suggests that one farm hob took umbrage when the farmer’s new wife cut back on household expenditure and replaced the cream regularly left out for him overnight with skimmed milk. The offended hob not only stopped performing the household chores, but it began to make strange noises and tear the covers from the bed in the middle of the night, and even killed the poultry.

Houses which had a reputation for ‘poltergeist’-style hauntings (prior to the first use of this German loanword in an English context by the Society for Psychical Research in the late nineteenth century) were frequently known colloquially as ‘boggart houses’. Several examples are found in West Yorkshire, including at Midgley, Brighouse and Leeds, where a whole council estate has inherited the name from the now-demolished house on whose site it stands. It was famously applied to Bierley Hall near Cleckheaton sometime in the early 1800s, when the manifestations in one upstairs room of the building grew so violent that crowds of people gathered outside hoping to glimpse the phenomena, whilst numerous attempts were made to exorcise the room by clergyman and cunning folk, but all to no avail.

If the hob or boggart began to behave in such a fashion, it also became notoriously difficult to get rid of. In a story which rivals the narrative of the gifting of clothes for its ubiquity and geographical spread, the spirit becomes so troublesome and tenacious that the family decides to move house and leave it behind. To this end, they quietly pack up all their belongings onto a cart and creep out of their former home early one morning. When they are only a short distance down the road, a neighbour sees them and enquires as to what is happening, to which the voice of the boggart responds from the cart, ‘We’re flitting!’ The family abandon their flight and return to their old home, resigned to the fact that if they are going to be harassed, they might as well be harassed in familiar surroundings.

This is another classic example of a migratory legend, which is told about different locations across Yorkshire from the Holderness coast, to Cliviger on the Lancashire border – not to mention several neighbouring counties. It is now impossible to tell exactly where the narrative originated from, but despite its frequent appearance in collections of the county’s folklore today, Reverend J.C. Atkinson for one doubted that it originated in Yorkshire. However much the boggart stubbornly refuses to be evicted, Atkinson suggests that any Yorkshireman is more stubborn still and would not be driven from his home by a mere spirit. From his extensive forty years’ experience as vicar of Danby, he notes that, ‘Flitting is, like matrimony, “not to be lightly or wantonly taken in hand”; and, still less, abandoned after the said fashion.’

Nonetheless, the tale colourfully makes the point that ridding your family of a troublesome boggart was not an easy prospect. At one time they were evidently considered such a nuisance around Yeadon in West Yorkshire, that the town accounts actually record sums paid from the public purse for ‘boggart-catching’! In many stories, priests or cunning folk have to be called in and they must resort to imaginative tactics to succeed. Whilst the clergy were unable to exorcise Bierley Hall’s resident spook, in other places intervention proved more effective. For instance, the prayers of three men of the cloth succeeded in coaxing Robin Round-Cap from Spaldington Hall into the confines of a nearby well, where he was condemned to remain for a certain number of years.

The prolific nineteenth-century Yorkshire antiquarian, Harry Speight, suggested that it was the hobs and boggarts who had been forced to leave their homes – whether through taking offence or compulsion – that subsequently became an even greater nuisance to unwary travellers in the wild. Following its departure from Close House, he suggests the boggart has ‘ever since been wandering through the dale and field, an idle worthless wight, no good to anyone and tempting others to idle, evil ways.’ Whilst no folk narrative makes this trajectory clear itself, the notion nicely accounts for the seeming disparity between relatively well-behaved domestic hobs or boggarts (such as Hob of Hart Hall) and the less-civilised, more naturally malignant examples which roamed the countryside.

Hob Holes at Runswick Bay, home to a malevolent hob. (Kai Roberts)

The hob that gave its name to Hob Hole, a large sea cave in Runswick Bay on the North Yorkshire coast, retained some vestige of its former generosity. In less enlightened times, local mothers took their children there at low tide to beg a cure for whooping cough, invoking the spirit with the words,

Hob Hole hob, my bairn’s gotten t’kin cough

Tak ‘t off, Tak ‘t off!

However, one source adds that when the hob was not remedying common childhood illnesses, he ‘used to wander over the moors behind the bay with a lantern and often decoyed travellers into the pots to be found amongst the rock or else in a driving night storm of rain would offer them shelter in his hole and leave them to perish by the incoming tide.’

Hobs and boggarts in the wild were often associated with caves and potholes. In ‘The Boggart of Hellen Pot’, Victorian folklorist Sabine Baring-Gould narrates a first-hand account in which he finds himself lost at night in the limestone country between Pen-y-ghent and Arncliffe – an area riddled with such chasms. Stumbling blindly across the moors, he encounters a lame man, who, despite never speaking, seems to be leading him to safety. Baring-Gould notes ‘The impression forced itself on me that just thus would a man walk who had his neck and legs broken ...’ But after taking him some distance along the bed of a stream, the strange man vanishes, leaving the unwary traveller to stagger on in the darkness. Then, suddenly he reappears, just as his victim is teetering on the edge of Hull Pot – a vast, gaping rent in the fabric of the landscape – and tries to drag him down. Baring-Gould only saves himself by clinging to a rowan tree which overhung the precipice.

Baring-Gould was a notorious romanticist and it seems unlikely that he was recounting an incident that he actually experienced personally. However, it probably does record a narrative that was popular in the Three Peaks region of Ribblesdale in the nineteenth century. At Hurtle Pot, a pothole near Chapel-le-Dale in the same area, a boggart was once believed to pull unfortunate passers-by down into the hole and drown them in the murky depths. A local writer remarks, ‘Both this and Jingle Pot are choked with water from subterranean channels in flood time and then there is heard such an intermittent throbbing, gurgling noise, accompanied by what seems dismal gaspings, that a timorous listener might easily believe the boggart was drowning his victims.’

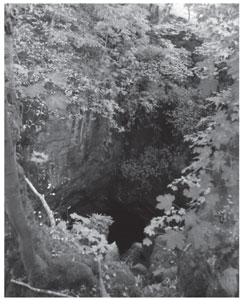

Hurtle Pot near Chapel-le-Dale, home to a malevolent boggart. (Kathryn Wilson)

Meanwhile, in the lead mining district around Grassington and Greenhow Hill, the miners had their own tutelary spirits with a similar dual nature to hobs and boggarts. Locally they were known as the Ghostly Shift, but miners who had migrated to Yorkshire from Cornwall brought with them their own term – the ‘Knockers’. These spirits were so-called due to their tendency to make mysterious, loud rapping noises, especially in new workings. In some cases, the miners believed these sounds to be a sign that they were nearing a rich seam; in other instances, however, they were regarded as portents of disaster and thought to occur just before any serious accident. Often in those cases, superstition amongst the miners was such that they refused to continue work until further safety precautions had been taken.

The association between such beings and chthonic regions suggests some relation to the ancestors. The Knockers or Ghostly Shift were quite explicitly regarded as the personification of all the miners who had died in shaft falls over the generations, but whilst in the case of household or other tutelary spirits the connection with the dead is not so unequivocal, such correspondences suggest that hobs and boggarts may be a corrupted remembrance of the ancestral spirits that are a common tradition across many non-monotheistic world views. Although the Victorian conceit that all folklore is a fossilised relic of pre-Christian pagan practices has largely been discredited, it is nonetheless possible to draw valuable parallels with beliefs in other pre-modern cultures, as long as they are not overstated.

The Roman ‘Lares’

are the most notable example in this respect. Classical literature indicates that these benign household spirits were believed to be the personification of all the ancestors who had been buried beneath the house, or the foundation sacrifice offered when the structure was built – both common practices in pre-modern societies. The correspondence between the Lares

and British household, or tutelary, spirits was observed as early as 1605, by Pierre de Loyer in his

Treatise of Spectres or Strange Sights, Visions and Apparitions appearing sensibly unto Men

,

and it is not unreasonable to suggest that hobs and boggarts were descended from a similar tradition, as there is evidence that both household burial and foundation sacrifice were practised by some of the pre-Christian cultures of this country.

If the connection with caves – often regarded as liminal points and entrance portals to the underworld – is not sufficient to establish a relation between household and ancestral spirits, then it should be noted that we also find hobs and boggarts associated with the material remnants of ancient cultures. In Farndale, on the North York Moors, a hob notoriously haunted a prominent prehistoric burial cairn known as Obtrush Roque. Meanwhile, Lile Hob of Blea Moor seemed to guard a treasure of obscure antiquity. It haunted the moorland road between Newby Head and Gearstones, and was known for jumping onto passing carts in the dark and hitching a short ride before vanishing again. However, the hob apparently disappeared for good after a Dentdale farmer discovered ‘three armlets made of silver, inlaid with enamel’ on the moor and removed them to give to the landowner.