Folklore of Yorkshire (23 page)

Read Folklore of Yorkshire Online

Authors: Kai Roberts

Marston Moor, haunted by a victim of the Civil War conflict? (Kai Roberts)

As these examples suggest, as the centuries wore on, ghosts went from primarily haunting people to haunting places. In medieval and early modern narratives, the exact location at which a ghost was encountered was rarely considered important and nor was it necessarily bound by it. However, by the eighteenth and nineteenth century, apparitions were nearly all fixed in space: whether it be the site of a terrible tragedy, unconsecrated burial or just one of those liminal points so often associated with the supernatural. As a feature of this development, the concept of the ‘haunted house’ grew increasingly prominent. Whilst ghosts may have appeared in buildings previously, they were typically a transient phenomena; the idea of the irredeemably haunted house, whose ghost disturbed generations of residents, was a later product and arguably one fostered by the emergence of Gothic literature in the late 1700s.

Interestingly, the ghosts that began to haunt houses in this period were more often felt or heard rather than seen, and whilst they were undoubtedly regarded as the spirit of some individual who had probably once lived there, they were not always identified with any specific person. Grassington Old Hall, for instance, was widely reckoned to be haunted and locals avoided passing that way at night, but the manifestations rarely amounted to much more than unearthly noises and the patter of disembodied feet on the staircase. Similarly, the peace at Easington Hall in Holderness (now demolished) was often shattered by rushing noises and the swish of a dress on the stairs, whilst a groaning, bellowing noise sometimes sounded from the cellar. Raydale House, near Semerwater, was particularly disturbed by a ‘noisy spirit’ known as ‘Auld ‘Opper’, which used to rap on various items of furniture and knock furiously at the door.

Whilst these ghosts may have been raucous, they were never hostile and in the early nineteenth century at least, their nature seemed to be regarded as different from those violent manifestations which were regarded as the work of boggarts. However, it is difficult to tell how much this distinction was a product of the popular imagination at the time, and how much was imposed by the folklorists who recorded the material. Nonetheless, both seem to have been precursors to the modern ‘poltergeist’, which did not emerge as a separate category in the English tradition until 1848, when this German loanword was popularised by Catherine Crowe in her seminal compendium,

The Night Side of Nature

. Prior to this, such hauntings had been associated with demons and witchcraft as much as the spirits of the dead. Indeed, the connection has always been tenuous and poltergeists increasingly became regarded as psychic phenomena, rather than interventions from beyond the grave.

Yet, although the ghosts of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries rarely seemed to be able to interact with the material world in the manner of a poltergeist, these restless spirits were often regarded as such a nuisance that they had to be laid. A dissolute former resident of Low Hall at Appletreewick, by the name of Thomas Preston, tormented the household with a variety of auditory phenomena: ‘Unearthly sounds were often heard; the oaken rack rattled most mysteriously, doors banged fearsomely, the rafters often creaking with no apparent cause. On stormy nights hollowed sepulchral groans proceeded from the roof.’ The tenants grew so disturbed by these occurrences that they eventually had the spirit confined to a spring in Dibb Gill, known thereafter as Preston’s Well.

The motif of trapping troublesome ghosts in watery places was a common one, and the Blue Lady that haunted Heath Old Hall, near Wakefield, befell a similar fate. She was thought to be the ghost of Lady Bolles, a former owner of the hall who had died in 1662, leaving instruction that her bedchamber be shut up for evermore. When this command was violated some decades later, her apparitions began to be seen gliding through the passages of the house and the coach road leading up to it. Eventually, however, her spirit was condemned to a pool on the banks of the river to which she gave her name. Yet such exorcism rarely proved successfully; the Blue Lady was still occasionally seen at Heath Old Hall, much as the ghost of Sir Walter was seen at Calverley Hall some time after he was laid for ‘as long as green holly grows’.

The failures of these exorcisms doubtless reflected the on-going anxiety which post-Reformation theology had fostered in the population regarding the supernatural. People did not have faith in the capacity of Protestant ministers to banish evil spirits and Reverend J.C. Atkinson records an occasion when an elderly Danby parishioner asked him to expel a spectre haunting her house: ‘I told her at last I could not, did not profess to “lay spirits”; and her reply was “Ay, but if I had sent for a priest o’ t’ au’d church, he was a’ deean it. They wur a vast mair powerful conjurers than you Church-priests”.’ This experience reaffirms just how much the ghost tradition in Yorkshire was a product of the Reformation and the theological debates that followed. Rather than rid the world of superstition, Protestantism had imbued the supernatural with a newly devilish intent, and found itself with no defence against ghosts or those who believed in them.

W

ATER

L

ORE

![]()

E

nglish folklore brims with legends pertaining to water sources; from lakes and rivers to wells and springs. It is hardly surprising that the medium should have exerted such a powerful fascination over the superstitious mind. Water is a fickle, dualistic element: on the one hand, it is essential for the maintenance of life; but on the other, it can snatch life away in an instant. It has the capacity to both reflect or distort an image; to reveal or deceive, like an illusionist playing games. Meanwhile, water has strongly liminal connotations. On the purely corporeal plane, a watercourse can divide physical territories, representing a no-man’s land between this bank and the yonder shore. We have seen how such thresholds resonated in the pre-modern psyche, and water embodies more than one boundary: it springs mysteriously forth from the hidden places of the earth and conceals a murky netherworld beneath its surface, forming a portal between this realm and another.

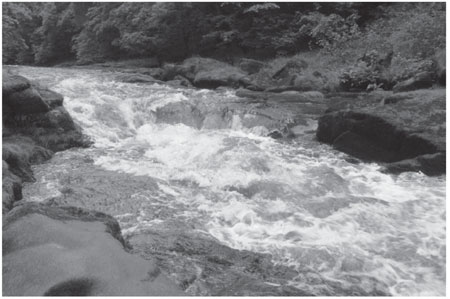

As many residents will attest, Yorkshire can be a very wet part of the country and whilst it does not have many natural lakes, it has no shortage of rivers and streams. A number of these can be quite treacherous – especially when they are in spate or must be crossed by means other than a bridge – so it seems natural that their danger should have been personified in an array of sinister genius loci. It is an impulse which has endured into modern times, and the successful 1973 public information film featuring the Spirit of Dark and Lonely Water is arguably a late twentieth-century expression of exactly the same imaginative process that once populated our lakes, rivers, ponds and bogs with kelpies, grindylows and all manner of comparable terrors.

The kelpie, or water-horse, is the most widespread image associated with water sources and whilst it is particularly characteristic of Ireland, Scotland and Wales, northern England has its fair share as well. For instance, a stretch of the River Ure, near Middleham in Wensleydale, is believed to be plagued by just such a fiend, which ‘riseth from the stream at eventide and rampeth along the meadows eager for prey.’ It is thought to take at least one human victim per year and sometimes many more. Clearly in previous centuries the vicinity of Middleham was once an important crossing point over the River Ure, and the ford particularly hazardous after heavy rainfall, as similar remarks are made about its nature in the legend concerning the construction of Kilgram Bridge (

See

Chapter Six).

The River Ure in spate in Wensleydale. (Kai Roberts)

An even more famous water-horse haunts the Bolton Strid in Wharfedale. Of course, this notorious spot is an exemplary location for such a legend as it is universally regarded as one of the most dangerous stretches of water in the entire British Isles. At this point, the River Wharfe rapidly narrows from approximately 80 feet wide to a mere 8 feet over a distance of only 300 yards. The majority of the water has eroded downwards through the rock, meaning that the depth of the Strid is considerable and due to the ferocity of the current flowing through it, impossible to fathom accurately. The rocks surrounding the channel are often extremely slippery and over the ages, numerous foolhardy individuals have attempted to jump across the narrow breach; no one who has fallen into the Strid has ever survived and even their corpses go unrecovered.

One apocryphal legend holds that nearby Bolton Abbey was founded in the twelfth century on land donated to the Augustinian canons by Lady Alice de Romilly, after her son drowned in the Strid when his horse unsuccessfully tried to jump it during a hunt. The episode was immortalised by William Wordsworth in his poem of 1807, ‘The Force of Prayer’, although sadly the legend does not appear to have any historical foundation. Another legend connected with the Strid holds that three sisters – the heiresses of Beamsley Hall – kept watch at the Strid one May Day morning, hoping to see its fearsome water-horse and that by expressing their dearest wishes to it, they might, by magic, be brought to fruition. However, these siblings ought to have known better; for the spectral steed is only seen to emerge from the churning white waters prior to a fatality and whilst they may have witnessed it ride, not one of the three sisters returned to Beamsley Hall that day.

The perilous Bolton Strid, where a fairy steed rides on May Day morn. (Kai Roberts)

Whilst horses seem to be the most common embodiment of a perilous river, more anthropomorphic spectres have also been recorded, and a ford across the River Dove in Farndale on the North York Moors was once renowned as the haunt of a spirit known as Sarkless Kitty. She was said to manifest in the form of a striking young maiden without a shred of clothing to preserve her modesty – hence the title ‘Sarkless’ which in the local dialect means ‘without a dress’. Kitty was supposed to appear to young men on the opposite bank of the Dove and using her beauty, tempt them to their deaths in the treacherous waters. The ghost was associated with a Gillamoor girl called Kitty Garthwaite, who, in 1787, had committed suicide in the river after being abandoned by her fiancé and like so many suicides in that era, was refused burial in consecrated ground.

Yet, it seems that this connection is mistaken, for there is evidence to suggest that the spot was already regarded as haunted years before Kitty Garthwaite’s death. It seems more likely that her story was attached to a much older water spirit, whose legend arose as an animistic personification of the River Dove. Either way, at the peak of local belief in the tale, from the late eighteenth to early nineteenth century, at least eighteen victims were attributed to Kitty. Following the death of a popular young farmer in 1809, local feeling ran so high that the vicar of Lastingham was summoned to perform an exorcism on the ford. It seems unlikely that any fewer people died in those dangerous waters as a result of such an intervention, but nonetheless, the country folk were satisfied that Kitty had been laid and refused to even mention her name thereafter, lest she rise to torment them again.