Read Folklore of Yorkshire Online

Authors: Kai Roberts

Folklore of Yorkshire (26 page)

Lady Well at Threshfield, whose waters could ward off evil spirits. (Kai Roberts)

However, wells were not universally favoured by spirits: in some instances, their consecrated waters were an effective defence against them and such was the case at Lady Well, near Threshfield. Local legend reports that Threshfield Grammar School was once sorely troubled by a ghost known as Pam the Fiddler, who resembled a ‘wizened owd man, summat of a monkey sort, covered with soft downy hair.’ Old Pam was a merry spirit who was often heard to fiddle all night in the schoolrooms, accompanied by the shouts and laughter of his spectral party guests, whilst an uncanny illumination streamed from the windows. Many locals were quite fond of Pam, but the schoolmasters hated him and frequently complained about his presence distracting the pupils, as he paced the upper floor or slammed doors shut with abandon.

One night, a drunken tinker named Daniel Cooper was passing by the school at a late hour as he returned home from the pub. Seeing that eerie light from the windows, he knew that Pam’s revels must be in full swing and thought to spy on their carousing. Unfortunately, however, he attracted the attention of the assembled spirits with a sneeze, and, furious with the tinker’s imposition, they pursued him into the night. Fearful for his soul, Daniel took refuge in the middle of nearby Lady Well, but whilst Pam and his entourage dare not pluck their prey from its sacred waters, they remained on guard at a safe distance. As a result, Daniel was forced to spend the night immersed up to his neck in bitterly cold water, until the cock finally crowed and dawn drove the ghosts away. Yet, despite his ordeal in the icy well, he is said to have emerged with renewed vigour – doubtless a testament to the healing properties of those holy waters.

S

ECRET

T

UNNELS

AND

B

URIED

T

REASURE

![]()

S

ecret tunnels are one of the most ubiquitous motifs in English folklore: in every locality, there is bound to be some tavern, church, mansion or ruin to which the legend of a hidden conduit is attached. In many cases, these rumours of lost subterranean passages have survived into the present day, whilst they have been reinvented for recent generations through tales of Cold War nuclear bunkers and classified government installations. These mysterious underground networks seem to exert a powerful influence over the collective psyche and no matter how many times the reports are debunked, belief in their existence persists.

There are good reasons for this. Over the centuries, actual secret tunnels have been constructed – then forgotten about and rediscovered – for numerous purposes: for instance, to enable smugglers to evade the Customs & Excise men; to permit nobles to escape a besieged castle; or to allow priests access to a Catholic house unhindered during the Reformation. Equally, old buildings often seem to display signs of such clandestine passageways, although when properly excavated they mostly prove to be little more than the remains of an ancient drain or ice-house.

Pseudo-historical narrative and superficial evidence are woven around every tunnel rumour to lend a veneer of plausibility, which can whet the appetite of even the most circumspect local historian. Typically, however, the game is often given away by the impossibility of the structure. The tunnels of local folklore invariably run an unfeasible length or traverse impractical terrain. Some are supposed to pass beneath rivers, where the workings would quickly flood and collapse, or between points of radically different altitude. Whilst our ancestors were often remarkable engineers, such feats were undoubtedly beyond them.

As if secret tunnels were not themselves sufficiently stimulating to the imagination, they also proved fertile ground for more fantastic speculation. Supernatural entities frequently haunted these passages, from beasts guarding them from unwelcome incursions to ghosts tracing the route as they had done in life. Following his leap from Scar Top at Netherton, the Devil still wanders the network of tunnels beneath Castle Hill near Huddersfield, whilst only a short distance away at Lepton, the headless ghost of Sir Richard ‘Black Dick’ Beaumont stalks the course of a tunnel between Whitley Hall and a folly known as Black Dick’s Tower.

Tunnels are also known as one of many repositories for that other staple of local legend – buried treasure. Again, such rumours have a greater credibility than many pre-modern folk beliefs. Prehistoric and Anglo-Saxon burial mounds have been known to yield valuable grave goods, whilst prior to the existence of a proper banking system, burial was often the only way of securing personal wealth against the vicissitudes of fortune. During troubled times from the Roman occupation through the Dark Ages to the medieval period, men of property have entrusted their savings to the earth and for various reasons, never returned to reclaim it.

Archaeologist-cum-folklorist Leslie Grinsell, who made a study of treasure legends relating to prehistoric sites, remarked, ‘It is natural that in regions where explorations resulted in finding objects of material value, folk traditions of buried treasure would develop and not only become attached to sites where treasure may have been found, but also spread to other barrows in the region and ancient monuments generally.’ Indeed, across Yorkshire legends of buried treasure are found associated not only with prehistoric burial mounds, but standing stones, waymarkers and the ruins of castle or monasteries.

It is not difficult to see the appeal of legends concerning buried treasure. The prospect of acquiring wealth, without any of the attendant labour so often involved, is attractive in any age. However, it is clear that during the medieval and early modern period, such legends were taken very seriously indeed. By 1542, so many wayside crosses and boundary markers were being pulled down in the belief that riches lay buried below, that Henry VIII was moved to enact a statute proscribing treasure-hunting. Meanwhile, local gossip often attributed the financial ascendance of certain families to the discovery of buried treasure, and ‘hill-digger’ was a popular term of abuse for the nouveau-riche of the age.

Like secret tunnels, some treasure legends came with a suggestion of historical authenticity. The Nortons of Craven were a wealthy local family in the Middle Ages believed to have hidden their fortune in Norton Tower, their hunting lodge on Rylstone Fell, prior to the family’s extinction following their support for the Pilgrimage of Grace. Similarly, during the 1745 rising, a Jacobite hoard had supposedly been buried in a curious knoll known as Silver Hill at Stanbury, a region of the county in which many members of the local gentry had been sympathetic to the Young Pretender’s doomed claim to the British throne. As late as 1899, local author Halliwell Sutcliffe noted, ‘The fields which climb this hill were well tilled aforetime through being constantly turned over in search of the treasure.’

Yet, whilst some such legends exhibit a semblance of probability, there is a far greater corpus which seem overtly incredible. Not only are these treasures located in impossible topographies, revealed or guarded by strange supernatural beings, the associated narratives also employ a body of phantasmagorical symbolism, the key to which we have long since forgotten. As a result, some of these stories appear quite impenetrable today, albeit in a pleasingly dreamlike fashion. Yet, it undoubtedly seems as if the legends are meant to encode some esoteric knowledge or some valuable moral, offering much opportunity for febrile speculation.

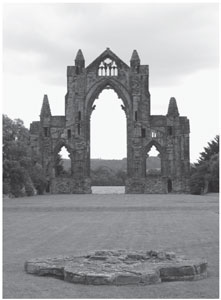

The ruins of Gisborough Priory, location of buried treasure. (Kai Roberts)

Certainly, in many narratives, the unobtainable nature of the treasure is emphasised. An archetypal version of these legends is attached to Gisborough in Cleveland, where a tunnel was rumoured to run over a mile from the ruined priory to a district known as Tocketts. At the midway point of this tunnel, there was supposedly a large chest of gold constantly watched over by a bird of the corvid family. When one brave individual attempted to procure the treasure for himself, he found himself ‘terribly used by its guardian, the crow, which suddenly became transformed into His Satanic Majesty.’ In later folklore, a phantom black monk prowls the priory ruins to guard the treasure against seekers.

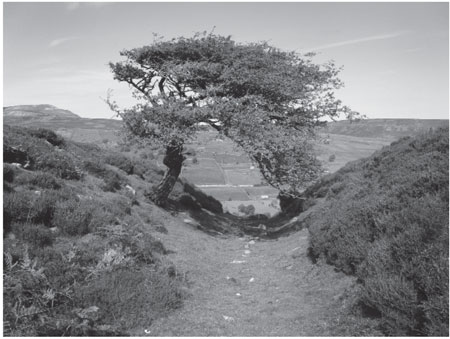

A variation on this tale is told about the prehistoric earthwork (possibly an Iron-Age enclosure) known as Maiden Castle, on Harkerside in Swaledale. Although the treasure buried beneath was notorious, legend maintained that only one band of fortune-hunters had ever actually laid eyes on it. When they tried to open the chest, a black hen appeared and flapped her wings so violently that it put out their light, and left them unable to approach the chest. This happened three times and eventually the men had to quit. They returned the following day, but this time they were assailed by such a ferocious storm that they never even found the chest again.

Birds of some description – typically corvids or poultry – are frequently portrayed as the guardians of the treasure, although in some instances they are accompanied by other incongruous beasts. Indeed, these more elaborate narratives tend to be bizarre in several respects. For instance, a legend attached to the ruins of Kirkstall Abbey, near Leeds, tells the story of a local man who had a particularly curious experience involving a hidden tunnel, mysterious treasure and its unusual guardians.

Maiden Castle, a prehistoric enclosure above Swaledale and the location of buried treasure. (Kai Roberts)

Kirkstall Abbey near Leeds, location of buried treasure. (Kai Roberts)

This Kirkstall man had been threshing corn in the abbey grounds and as he was taking a break at midday, he observed a cavity in the ruins which he had never noticed before. Further investigation revealed an underground passage which, in the spirit of inquiry, he pursued for some considerable distance until it suddenly opened out, and he discovered himself standing in a great hall with a fire blazing in the hearth. Even more oddly, a black horse stood in one corner, behind which sat a large oaken chest with a cock watching over it.

Suspecting the chest contained treasure, the man resolved to acquire it for himself and approached. However, as he drew closer ‘t’horse whinnied higher and higher, and cock crowed louder and louder, an when he laid his hand on t’kist, t’horse made such a din, an t’cock crowed and flapped his wings, and summat fetched him such a flap on t’side of his head as felled him flat an he knowed nowt more till he came to hisself and he war lying on’t common.’ The man searched for the entrance to that secret passage many times over the years, but he was never able to find it again.