Forgotten Voices of the Somme (18 page)

Read Forgotten Voices of the Somme Online

Authors: Joshua Levine

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Military, #World War I

I didn't know when my moment would come. I expected it at any moment. The best thing I could do was to lie low and keep quiet. Another wave of troops came over, and as they were passing, the enemy fire hotted up. They went farther on to meet the same fate. When the fire died down a bit, I looked around for a shell-hole and found one, but it was chock-a-block full of dead, wounded, unwounded perhaps, and I couldn't get in it, so I had to stay on the surface. One man was trying to worm his way back to the front-line trench on

his hands. He said, 'Give us a hand!' Soon after he said that, a big shell dropped close by. And he got up and ran like a shot.

2nd Battalion, Royal Berkshire Regiment

I was given a place with my signallers about four hundred yards behind our front line on a bank where you could see very clearly on a fine day. The troops advanced out of the trenches, but by this time, although the sky was clear, the shells had thrown so much smoke, rubble, and a reddish dust was over everything. There was a mist, too, and hardly anything was visible.

One saw these figures disappear into the mist, and as they did so, so did the first shots ring out from the other side. I thought our men had got into the German trench – and so did the men that were with me. I reported as such to the division. I said, 'I'm going forward, I can't really see what's happened.' I got a message to stay where I was, so I stayed. Presently, as the barrage went forward, so the air cleared and I could see what was happening.

In the distance, I saw the barrage bounding on towards Pozières, the third German line. In no-man's-land were heaps of dead, with Germans almost standing up in their trenches, well over the top – firing and sniping at those who had taken refuge in the shell-holes. On the right, there were signs of fighting, and I saw Very and signal lights go up in the trenches.

Then I waited, and another brigade was ordered to resume the attack. Providentially for that brigade, the order was cancelled when greater realisation came in as to what had really happened. It was the most enormous disaster.

Lieutenant A. Dickinson

10th Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment

The air was full of bullets. Men began to fall all around us. It was tragic. When these men were hit, they just fell flat on their faces. One bullet went between my fingers; it just clipped the edge of each. When we came to want something to eat, when you got your haversack off your back, you found that the bullets had gone through your Maconochie ration, or tin of bully beef. Some very near misses.

When we arrived at the mine crater, our orders were to man the lip. Of course, the Germans played their machine guns on the lip, and one after the

other, men were hit in the head, and rolled down into the bottom of the crater, which tapered down to a point. It was still hot as an oven down there.

Lieutenant Cecil Lewis

3 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps

We flew right down to three thousand feet to see what was happening. Of course, we had this very well worked-out technique which was that we had a klaxon horn on the undercarriage and I had the button and I used to press out a letter, and that letter was to tell the infantry that we wanted to know where they were. And when they heard us hawking at them from above, they had red Bengal

flares

in their pockets, just like the little things one lights on the fifth of November. And the idea was that as soon as they heard us make our noises above, they would put a match to their flares, and all along the lines, wherever there was a chap, there'd be a flare. And we'd note these flares down on the maps and Bob's your uncle. But, of course, it was one thing to practise it, another thing to really do it when they were under fire. Particularly when things began to go a bit badly. Then, of course, they jolly well wouldn't light anything, and small blame to them, because it drew the fire of the enemy on to them at once. So we went down on that particular morning, looking for flares all around La Boisselle, and down to Fricourt, and I think we got two flares on the whole front. And of course we were bitterly disappointed, because this was our part to help the infantry – and we weren't able to do it.

Private Tom Easton

21st Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers

We reached the German trench and we spread out, and there were few Germans in that trench, except the dead or wounded. We had many wounded of our own, and bombers were instructed to proceed up the communication trench, towards the village of La Boisselle. We spread out, and prepared to defend the trench from the other side, against attack. We found a German dugout, and it was immediately decided to make that the headquarters for the battalion. At that time, we only had one officer left, who became adjutant. I remember going into this dugout. It was about twelve steps down, and must have been twelve feet long and six feet wide, and it was safe from the ordinary 18-pounders, which was the calibre of shell that was used on front-line trenches. It was much more elaborate than the British trenches.

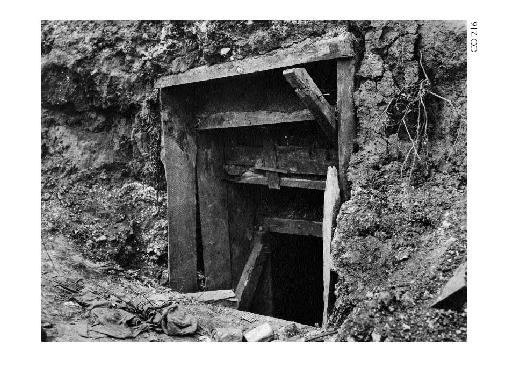

The entrance to a deep German dugout.

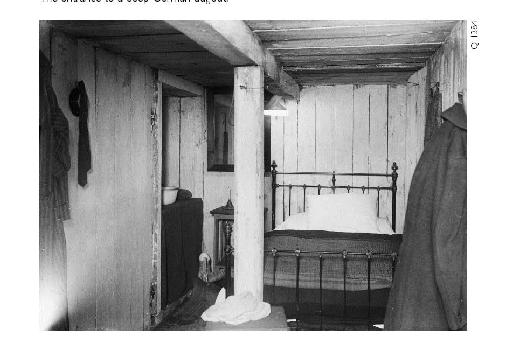

The interior of a German dugout.

Lieutenant Phillip Howe

10th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment

The trenches we had to get out of were deep, and it was necessary to climb up ladders. Naturally this made us a bit slow, so the people who came behind suffered many more casualties than those who got over first. I put down my survival to the fact that I was first over the top, and got almost as far as the German trenches, before anything happened.

I met a German officer whose idea was to attack us as we crossed no-man'sland and he was armed with a whole array of stick bombs which he proceeded to throw at me and I replied by trying to shoot my revolver. I missed every time and he missed with his stick bombs as well. After this had gone on for a few seconds – it seemed like hours – somebody kindly shot this German officer and I made my way on to the place I was told to go to originally, which was a map reference, a hundred yards behind the German front line.

I made my way to this little trench which I had seen by aerial photographs. I had started off with more or less the whole battalion, but I found myself in this trench with about twenty men. I had been shot through the hand, and we quickly discovered that we were surrounded on all four sides. So I got all the men down a dugout which had very steep sides, and twenty steps leading down from the trench at the top to the dugout below. Just then, another officer came along, who had been shot through the leg and wasn't particularly mobile.

I sat halfway up the dugout steps. I was not able to shoot because I was shot through the hand, but the other officer, who was only shot through the leg, was able to shoot, so he lay at the top of the steps looking down the trench both ways, shooting the Germans as they came around the corners. The men down below loaded the rifle, handed it up to me and I handed it up to him.

It seemed a very long time before anything happened but just as our ammunition was running out, some English troops came down the trench from our left and they said, 'Oh, what are you doing here?' We tried to explain, but they said that there was no Germans within miles. I told them that the Germans were just around the corner, but they wouldn't believe me, and they turned the corner, and I heard a crash of bombs. Me and my men ran the other way. What happened to the other people, I don't know. We went back to our own lines. The rest of the battalion who had followed me over the top at the beginning were all casualties. The few men I had got left was all that was left of the entire battalion.

Corporal Harry Fellows

1/4th Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers

On July 1, my brigade was allocated a section of the trench about six hundred yards north of Fricourt. We were up all night, and the most tremendous barrage I'd ever heard went on until nearly half past seven. A few minutes before that, the ground shook, and the crater at La Boisselle went up. For several minutes after, the debris from this was rattling on our steel helmets. At about nine o'clock, a stream of prisoners came down the communication trench. I'll never forget the look of terror in their eyes. They'd been under bombardment for a solid week, and some of them had their arms up and looked like they would need a surgical operation to get them down. Nothing more happened until about noon, and then we had the order to move forward. We got into the front line, and then we learnt what had happened. The

Green Howards

had been very reluctant to leave their trench, until an officer climbed on top of the parapet and urged the men over. Part of his citation reads, 'As he lay mortally wounded in the bottom of the trench, he continued to urge on his men.'

Lieutenant Norman Dillon

14th Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers

We were pioneers and we had to follow behind the leading troops at some distance, the idea being that we had to help to consolidate the newly won positions. The troops that went before us would pull out their trenching tools and make a scratchy line; that's where we came in. The idea was that we would follow on and enlarge those little scratches in the ground into proper trenches. It was all terribly badly managed. Any digging could have been done by the troops on the spot. Another thing we did was to turn around the old German line. It just meant putting barbed wire on the opposite side and cutting a fire-step on the other side of the trench. Of course, it had its disadvantages, because the deep dugouts faced the wrong way, which meant that any shell coming over might easily have popped down the stairs and exploded underneath.

Corporal H. Tansley

9th Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment

Just before three in the afternoon, I managed to crawl into a hole. I'd stayed

the flow of the blood in my groin. I knew how to apply pressure to stay the blood. There were casualties everywhere. More than the Royal Army Medical Corps could cope with. I must have lost consciousness for part of the time, then revived a bit, and asked them to get me away. 'Oh, yes, we'll come to you!' they said. It was really a godsend that they did pick me up, and bring me out. So many never got away. My battalion suffered casualties up to eighty per cent. The colonel was found a day later – shot to pieces – hanging on the German wire. His adjutant was by him.

Corporal Don Murray

8th Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

I began to creep back towards the line, through mud and shell-holes, and down into the trench, and still there was nobody there. Gradually, we congregated in ones and twos, and we mustered forty-three. We started off 1,060. We trained for twelve months, and it took twenty minutes to destroy us. We went back to the quartermaster's stores, and we passed the

Sherwood Foresters

, who were to attack after us, and take

Mouquet Farm

, which we were supposed to have taken. We got back to the stores. There were cookers there with stew in, everything ready for us. The quartermaster was an acting captain, and he said, 'Is the battalion on the march back?' A lance corporal was in charge, and he said, 'They're here . . .'

Private Tom Easton

21st Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers

Roll-call was taken next morning, outside Brigade Headquarters, and out of 890 men, we could only muster a company – less than two hundred. We only had one officer left standing. We were collected by a captain, who had not been in the battle, and after feeding we were marched off into billets. Captain

McClusky was the

only surviving officer that came back with our battalion, and he was made the adjutant. I was pleased to see that my brother was also present at the roll-call.

Private W. J. Senescall

11th Battalion, Suffolk Regiment