Forgotten Voices of the Somme (20 page)

Read Forgotten Voices of the Somme Online

Authors: Joshua Levine

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Military, #World War I

Then, I saw some retreating Germans with a gun, and I lay down and had a pop at them. I didn't see that I hit any of them. After that, I found Triangle Point and one or two of my platoon were there; not many of them. And there were other people besides. We settled down to improve the defensive position. There was a young lance corporal in charge, and eventually we settled down for the night. At the end of the evening, I had a good drink of coffee out of a dead German's water bottle. It had been a very hot day, and a very hot business altogether, and I was terribly thirsty. This caused me a good deal of trouble; the coffee upset my stomach. As we moved towards the village of Montauban, there were still some German machine-gunners firing away, but when we got close to the village they put up a white flag. Some of our men were detailed to clear out the dugouts, and I expect they

cleared them out

.

Sergeant Ernest Bryan

17th Battalion, King's Liverpool Regiment

We were behind a creeping barrage, that means to say a barrage chucked down twenty yards in front of you, and then it's supposed to go on to the German front line for a minute only, and then lift, and that was our chance to charge and get in. But it was nothing like that. We never saw any lift, and we couldn't tell if shells were our own, or the Germans'.

We went about twenty-five yards, and got through what was left of our wire, stumbling through the front line. It was only then I realised what a terrible weight we were carrying. I was carrying a loaded Lewis gun, weighing just under thirty pounds. When we got towards their front line, up pops their machine gun, and chained to this gun was a German. The first thing I did was sling my Lewis gun under my arm and press the trigger. The German gunner went down; whether he was hit or not I didn't know and I didn't care, he was down. I sprayed right along the top, to keep the Germans' heads down. That gave us a chance of getting in.

When we got into the German front line, the fun started. We were getting enfilade fire from right and left. From rifle, and machine-gun fire, and also from artillery. My immediate concern was to get my Lewis gun on to the trench. We stayed an hour there, until all the objectives were gained – not only by our battalion, but also by the French on our right. Then we moved forward. Our colonel picked out a piece of land, and we dug in a hundred yards ahead. And we were carrying such a hell of a weight that we were

exhausted, but that's no excuse! You were still carrying a trenching tool, and a spade was stuck on your back. You pull that down, and start digging a new trench. We knew why; we knew very well that all the Germans would start shelling their old trenches. They had their range all right, but not the range of the new trenches that we were digging.

Henry Holdstock

6 Squadron, Royal Naval Air Service

There was great excitement. We had the news that some German prisoners were coming in, so we ran to the chalk-covered road that ran to the base and, sure enough, there was a young infantry officer there, walking with a German officer, and about seventy to 120 German prisoners walking behind them, very dejected, with pale yellow faces and German pill-box hats. I remember the expressions on their faces when they saw us. They could see we were navy, and we could see them pointing at us, and saying to themselves that not only were they fighting against the British Army, but they were fighting against the navy as well. They were all pointing to us with great excitement as they walked down, out of the war for ever. Which I thought was very nice. And the two officers were walking side by side, quite at peace. Two hours before, they'd been trying to kill each other, and now they're walking off almost hand in hand, with their little brood behind them, going back to captivity and safety. For me, it was very affecting to watch.

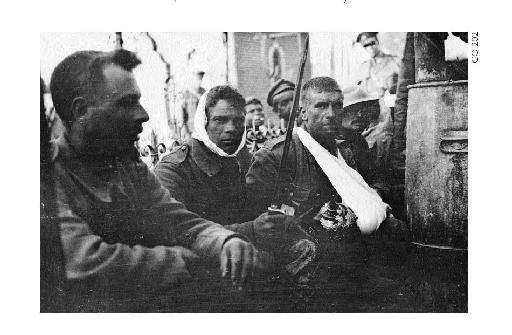

Sergeant James Payne

16th Battalion, Manchester Regiment

We walked on and came to a trench with some German prisoners in it and one of them was a doctor. I asked this doctor to bind the corporal's foot up and he wouldn't. I told him to do it or I'd shoot him. He spoke English and he said, 'Blame your own government!' I said, 'You won't bind his foot up?' He said, 'No!' So I shot him. We had to walk fifteen miles until we found a railhead where I found an ambulance. There were some German prisoners on stretchers there. I tipped them off, put the corporal on and put him in the ambulance and saw him off. I walked on until I found another ambulance and I was taken off.

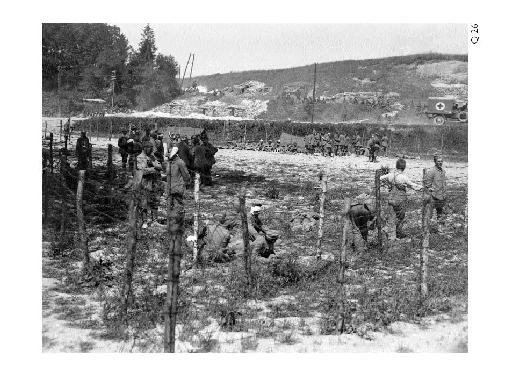

German prisoners captured on July 1, behind a wire 'cage'.

Private Albert Hurst

17th Battalion, Manchester Regiment

We had achieved our objectives, and, as far as we were concerned, all the attacking battalions must have been similarly successful. As it began to go dusk, we came under heavy artillery fire. One or two of the men were killed, and one man of our platoon had his leg blown off. Our biggest problem was shortage of water. I had none at all myself, because I'd had a bullet through my bottle. That night, the bombardment was heavy. Eighteen-pounders and whizz-bangs were firing at us. The Germans seemed to have our range, and I don't remember sleeping at all that night – or for the next three days. We were bombarded for three days, until we were finally relieved by another battalion, and by the end I was desperate. I was eating grass to try and get rid of my thirst.

Sergeant Ernest Bryan

17th Battalion, King's Liverpool Regiment

We were relieved on July 3. When we got back we were taken to

Bray

, and our brigadier thought it a good idea that warrant officers and senior NCOs should say what should have been done differently during the action. I saw the Lewis gunners and our officers looking at me. They knew how bitterly I'd felt at the terrific weight we'd been carrying. I asked the brigadier if it was possible for his brigade major to put our equipment on. He said, 'Certainly!' I got two Lewis gunners, privates, my boys, to put on everything: bombs in their pockets, sandbags, spade, kit, rations, extra ammunition round the neck, all full. I said, 'How do you feel?' The brigade major said, 'It's a hell of a weight.' I said, 'You haven't started! You forgot the rifle, you've got to put that up, and where are you going to carry it? Slung over your shoulders? You can't, because you've got to have it in your hand, ready. There's a farm field at the back here, just been ploughed. Try walking a hundred yards and see how you feel – and that's a playground compared with what we had to go over.' The brigadier said, 'You feel very much about it.' I said, 'Wouldn't you? Wouldn't anybody?'

Private Pat Kennedy

18th Battalion, Manchester Regiment

We didn't know that the day was a disaster. We didn't know that the only success was where our division and the

18th Division

gained their objectives. We thought the war would soon be over, and that our men were flushed with success.

It was long afterwards that we found out that the battle had been a disaster, except for us. We only heard about the shocking losses and the great numbers of wounded, from the Royal Army Medical Corps men. July 1 was a walkover for us, compared with the battle that followed. After we took Montauban, I though that we would get reinforcements and exploit our success. But nothing happened.

Major Alfred Irwin

8th Battalion, East Surrey Regiment

As we were taken out of the line, the

Canadians

had a Highland brigade in support of us. They were so impressed with the success of the few chaps of ours that were left, that they sent their pipers to play us out of the line. We have a connection with Glasgow, and our regimental march was familiar to the pipers, and they played that. It was a great compliment – but they were big, hefty chaps, and my little Londoners couldn't keep up at all. And they couldn't get the long step necessary for the swing of the kilt. So, although they played us out, it was rather an irregular march.

After that, drafts came in, and it was no longer the 8th East Surreys in spirit. All my best chaps had gone. We buried eight young officers in one grave, before we left. It was a terrible massacre. The attack should have been called off, until the wire was cut. They ought to have known through their intelligence the condition of the wire, before we ever got to July 1.

The success of these advances in the Montauban sector – at the cost of 1,740 lives – is often overlooked, or considered irrelevant, when placed alongside the sense of suffering and waste evoked by the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Yet, had a stronger reserve been in place, it is possible that the British army could have taken advantage of these advances, and broken through on the Montauban front. And it is certainly arguable that – even without a breakthrough – the day served its intended purpose; the Germans had been placed under great strain, and could no longer exert overbearing pressure on the French at Verdun.

The fact remains, however, that on a single day, 19,240 British and Dominion soldiers had been killed, and at least 35,493 wounded. In human terms, July 1, 1916 was nothing less than a disaster.

Lieutenant Ulick Burke

2nd Battalion, Devonshire Regiment

There was frustration. We'd lost so many people, and taken so little ground. And men began to wonder, '

Why

?' There was no feeling of giving up; they were just wondering 'why?' And when you came out into the billets, you saw these endless lines of walking wounded, and ambulances, and we wondered how long we could exist.

Corporal George Ashurst

1st Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers

Our battalion had five hundred casualties, and I'd lost most of my friends. These were my platoon lads, they'd been boozing with us in the villages. But it was no use bothering. We knew they'd gone.

Corporal Harry Fellows

12th Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers

When I came out of the line, having lost a lot of men, I'm sorry to say that I didn't feel any sadness. The only thing I thought about was that there were less mouths to feed, and I should get all those men's rations for a fortnight before the rations were cut down. That's all I can tell you honestly.

7th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment

Well, if I said the morale was high I'd be telling a lie. As a matter of fact, I think the thoughts of most of us, after the maiden attack, was that we wanted either a Blighty one or ones that were a top storey. We didn't want to be mutilated – that was our main thought. That, and smoking a cigarette, and wondering if it was going to be the last one.

Second Lieutenant W. J. Brockman

15th Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers

What was so wrong about it was that even though it was a complete failure, it was reported as being a success in the newspapers. And what was worse, was that they still persisted, knowing perfectly well that they were getting nowhere. It went on, and on, and on, and on.

A roll call of the 1st Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers after the first day of the Battle of the Somme.