Forgotten Voices of the Somme (17 page)

Read Forgotten Voices of the Somme Online

Authors: Joshua Levine

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Military, #World War I

As I was lying there, I had a drink out of my water bottle. I knew that Fritz couldn't touch me – unless he threw a bomb. On the left, I could see that the

Royal Fusiliers

were running back to their trenches. I thought Jerry was

counter-attacking, and I thought, 'What about me? If Jerry comes

here

, I'm for it!' So I made my mind up to move – bloody quick. I got up and dashed down the slope, and dived down into the sunken road once more. I was safe again and I found a few other men in there. We started to make a bit of a barrier against the slope.

Later on in the day, a message came across, saying, 'One officer, one NCO, twenty-five men ONLY to man the sunken road.' There was only the one officer in there, and I was a corporal, and we put a few men at either end of the road and some others in the middle of the road. Everything quietened down and we stayed there all night. The stretcher-bearers were very busy that night, though, and the wounded were cleared by the morning.

As dawn came, I was against the barrier and I heard voices coming from the other side. I stood up to have a look and I saw three Jerries a hundred yards away, stood in a ditch. I shouted, 'Jerries!' and I fired at the middle one. He disappeared. I don't know if I hit him, but we never saw them again. The officer came down to see what the trouble was – and I told him. He said, 'Right, lads, dig in now! Jerry's going to bloody well let us have it!' And he was right. Jerry started on us with

minenwerfers

. We could see them coming, and one dropped right on the body of men in the middle of the road, killing three of them, wounding the others. He dropped one on us – but it was a dud. Six yards past us – we were expecting it to blow us up – but it never went up. He dropped several more, but we had no more casualties.

As soon as it was dark, another messenger came, with word to evacuate the sunken road. So we ran back to our lines as fast as we could. We ended up back in the front line. And there were only a few men there. I didn't see any officers. Eventually, an officer came and picked us up, and we followed him down the communication trench, and he told us to bed down for the night. That night, the officer gave me an order to go back out into no-man's-land, to collect what rifles and identity discs I could, but I never did it. I'd had enough of no-man's-land. And I never saw the officer again.

Second Lieutenant W. J. Brockman

15th Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers

One fellow asked me to shoot him. He was half in and half out of a shell-hole, hopelessly wounded. But I didn't do it. I put his rifle on the ground and put his tin hat on top of it, hoping that somebody would find him.

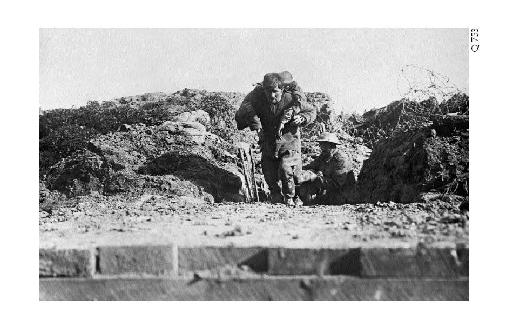

A wounded man is brought in along the sunken road at Beaumont Hamel on July 1.

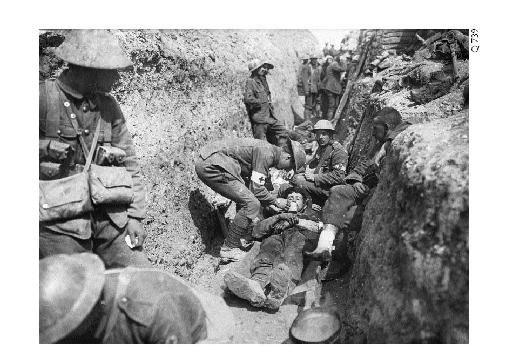

A wounded man of the 1st Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers is tended in the trenches.

Private Harold Startin

1st Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment

We had to bury the Newfoundlanders at Beaumont Hamel. If they were lying face downwards it wasn't too bad but if they were lying with their face up, and the sun had been shining on them, the faces were smothered in flies and bluebottles and it was enough to make you sick. There were no graves dug for them – they were put into shallows. You might get three, four, five or six into the crater and then you shovel down earth with a spade, and cover the bodies up. There were no crosses put there. We had no wood, we had no nails, we had no hammer. So they were just covered up and left.

Yes – death had no horrors then. Oh death, where is thy sting?

South of the Schwaben Redoubt, the German-held villages of Thiepval,

Ovillers

,

La Boisselle

and Fricourt all resisted the British advance. The 8th Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, starting from just outside

Authuille Wood

, managed to reach the third line of German trenches, but was beaten back. The 9th Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment, following in support, was cut apart by machine-gun fire from

Thiepval Spur

; 423 men of the battalion were killed.

The 21st Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers advanced to the north of the Lochnagar Crater – created by the explosion of the La Boisselle mine – and moved towards the village of La Boisselle, but was not able to hold its position.

The

10th Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment,

and the 11th Battalion, Suffolk Regiment, advanced alongside the crater, but were unable to make significant progress towards the German lines.

To the south, the 10th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment initially took six hundred yards of German front-line trench. However, its new position, on a down slope two hundred yards from Fricourt village, exposed the battalion to unrelenting machine-gun fire, and within two hours more than half of the battalion was dead.

10th Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment

At seven-thirty that morning, the ground rumbled, the trenches trembled, the earth rose up in the air and the explosion of the mine blackened out the sun.

Corporal Don Murray

8th Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

The previous night, at about 12pm, each dugout had a gallon bottle of rum put into the dugout. Nearly every man was drunk.

Blind drunk

. I thought to myself, this looks to me like a sacrifice. I never touched any. I determined to keep my head. Just as well I did.

At half past seven, Mr Morris – the officer with the lisp – pulled out his revolver, blew his whistle, and said, 'Over!' As he said it, a bullet hit him straight between the eyes and killed him. I went over with all the other boys. The barbed wire that was supposed to have been demolished had only been cut in places. Just a gap here, a gap there, and everyone made for the gaps in order to get through. There were supposed to be no Germans at all in the front line – but they were down in the ground in their concrete shelters. They just fired at the breeches in the wire and mowed us down. It seemed to me, eventually, I was the only man left. I couldn't see anybody at all. All I could see were men lying dead, men screaming, men on the barbed wire with their bowels hanging down, shrieking, and I thought, 'What can I do?' I was alone in a hell of fire and smoke and stink.

Corporal Wally Evans

8th Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

When we got into the German trenches, they changed hands several times. We advanced into the third line, got beaten back to the second, then beaten back to the first. We then found that we were being enfiladed by machine-gun fire, and bombed out with German bombs. There was no leadership and no orders, and I ran back into no-man's-land.

We went into action with twenty-five officers and 659 other ranks. At the end of the day, only 110 other ranks answered the roll-call. There were enormous losses. At night the battalion was withdrawn. What surprised us was the false information we'd been given that they were going to offer no resistance,

and there'd only be dead Germans in the trenches opposite us. Also, we felt that we'd been let down by our senior officers, three of whom left the battalion just before the battle. The commanding officer in charge had been made a brigadier-general, one major had gone to the back to be the town major and another had been told to report sick. So we were commanded by a captain. This aroused the men's feelings that they'd been left in the lurch at a very critical moment, and the very first test of our exploits as a new army.

75th Field Ambulance

, Royal Army Medical Corps

No one can describe what the Battle of the Somme was really like unless they were there. It was one continuous stream of wounded and dead and dying. You had to forget all sentiment. It was a case of getting on with the job. We went in action on the Somme the midnight before the action started. We took over a dressing station called

Black Horse Bridge, at Authuille Wood

. The field ambulance we were taking over from were taking rather a long time getting out, and we were all crouched down outside, waiting to get in, while shells were bursting around us. We used to put stretchers on wheels (we could run them down the road

if there was a road

at any time). Bits of shrapnel were sparking on these wheels, and we were wondering if we were going to live to get into this dressing station. Anyway we eventually got in.

When the ration party came up with supplies, it was two mules and a sergeant on horseback. A shell came over and burst right in the middle of them, killing them. The mules' heads and the horse's head were smashed clean off like a razor. All our dressing station outside was distempered with blood. We had four days and four nights there, and it was one continual stream of wounded. Our dugout was almost like a tunnel dug in the bank, and we used to have acetylene lights. Blasts from nearby shells would put these lights out, and the fumes from the light would be terrible, and we'd light it again.

I was assisting the doctor, holding the tray and instruments and torch for him. With the fumes and that, I started feeling faint, and he looked at me and said, 'Are you all right, Jackson?' I said, 'I am feeling a bit queer, sir.' He said, 'Go to the door, get some fresh air,' and he called another man to take over. That happened two or three times, but we had to keep going. This doctor was

Captain Beatty

, who became a Harley Street specialist after the war. He

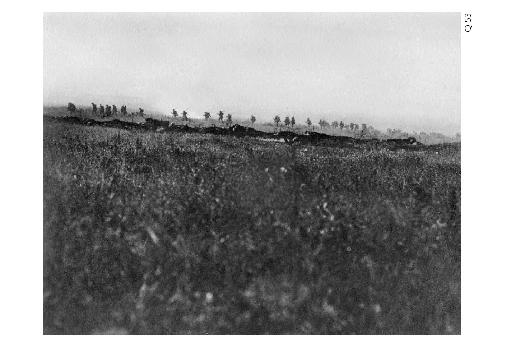

Men of

34th Division

advancing on La Boisselle.

was really marvellous; I don't know how he stuck it. He seemed to just carry on, as if he was in the theatre. He looked like a skeleton himself, thin and white.

I always remember one chap who was shell-shocked very bad. It took four or five of us to get him into the ambulance and hold him down. He thought we were taking him back into the trenches again, instead of taking him to hospital. And I remember one wounded man, who gave me a letter he had written. 'See this goes,' he said, 'it's to my wife, bless her heart!' So I said, 'Right! I will see that it goes!' A bit later, I went into a dugout to sleep. It was where they put the dead before they were picked up. I laid down on this improvised bunk, made out of wire netting, and I happened to see an arm on a stretcher, poking out from a blanket. I pulled the blanket over, and it was the chap who'd given me the letter. When things happened like that it really brought it home to you. Life seemed so cheap.

Corporal H. Tansley

9th Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment

We went through the lanes cut in the wire. After a while, I looked around for the line, and it seemed to have disappeared; they were lying around on the ground. There was severe machine-gun fire coming from

Pozières

, half-left. For a soldier who's been in battle, machine-gun fire is not so terrible a thing. It's a whistling sound. It didn't have such a shattering effect as the heavy explosive. As long as you dodged it you were out of it. But my mate, who was with me, went down, shot through the legs. In some cases, if it was a slight wound, some of the Tommies were quite pleased, because it meant they would be out of the war for a bit. I attended to my mate, and he had some qualms of conscience, because he wasn't facing the enemy when he went down. I didn't notice it myself, but he was an old regular soldier and it troubled him so much. I put a field dressing on him, and then he was hit again, through the mouth, and it killed him.