Fortune's Formula (32 page)

Authors: William Poundstone

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Investments & Securities, #General, #Stocks, #Games, #Gambling, #History, #United States, #20th Century

T

O MANY PORTFOLIO MANAGERS

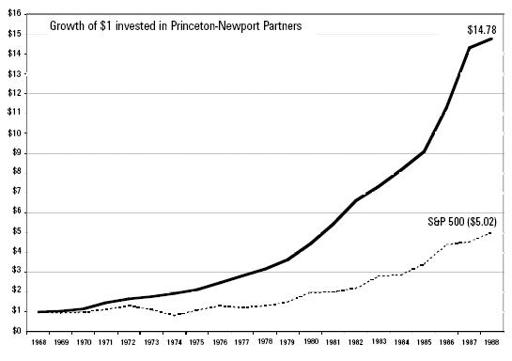

today, the nineteen-year record of Princeton-Newport Partners is the definitive home run. A dollar invested in the fund at the beginning of business in 1969 would have grown to about $14.78 by the time the fund ceased in 1988. Over nineteen years, the compound return rate averaged 15.1 percent annually after fees. The S&P 500 averaged an 8.8 percent annual return over the same period. Princeton-Newport’s investors beat the market by more than six percentage points.

Excess return is only part of the story. A few others achieved higher returns over comparably long periods. George Soros’s hedge funds modestly topped Princeton-Newport’s returns. Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway has had returns averaging more than 25 percent. (Thorp had to achieve about a 20 percent return to leave 15 percent for his investors. As a corporation, Berkshire Hathaway does not charge fees.)

The difference is that Buffett’s and Soros’s returns were much more volatile. The standard deviation of Princeton-Newport’s return was about 4 percent. That made the fund much less volatile than the stock market itself. The S&P 500 shed over a quarter of its value in 1974, and took a big hit on 1987’s Black Monday.

A chart of Princeton-Newport’s return looks nothing like the jittery graph of the sequential Kelly bettor’s wealth. Through diversification, fractional Kelly position sizes, and a philosophy of erring on the side of caution, Thorp achieved a smooth exponential growth refuting the conventional trade-off of risk and return.

Beating the Market

I

N

J

ANUARY

1989

, Giuliani resigned from his post of U.S. Attorney to run for mayor of New York. The first Princeton-Newport–related case to come to trial was that of Lisa Ann Jones, two months later. The main witness was William Hale. His story was detailed and believable. Until mid-1985, he said, Princeton-Newport had been buying back parked securities at the price paid, plus expenses. Then Berkman instructed Hale to “add or subtract something like $5 from the buy-back price” to make the parking less evident. This meant that there was an ongoing tab, money that Princeton-Newport owed Drexel or vice versa. Hale said the “parking lot” list was distributed to Regan, Berkman, Zarzecki, and Smotrich, all of the Princeton office. Hale ticked off a list of companies whose stock had been parked: Sony, American Express, Transco Energy, and Pulte Home Corporation.

Hale said that Regan “told me it was illegal.” Berkman told Hale “not to worry but to relax.”

Lisa Jones had left her family in New Jersey at the age of fourteen. By pretending to be eighteen, she got a job and an apartment. Eventually this led to the job at Drexel. In closing arguments, prosecuting attorney Mark Hanson showed that Jones had lied about her place of birth, education, age, and marital status: “a long litany of lies that has made up the tangled scheme of her life.”

It was by then clear that Jones was lying when she denied that stock parking went on. Jones was found guilty. Giuliani’s replacement, U.S. Attorney Benito Roman, said the verdict proves that the government takes perjury “very seriously.”

Jones was released on $100,000 bond and underwent “psychiatric counseling on the advice of her lawyer.”

The Princeton-Newport defendants went on trial in June 1989. The case was extensively covered, largely because it was seen as a bellwether for the Milken case.

The Wall Street Journal

, which generally sides with any security industry defendants short of serial killers, came down hard on Giuliani’s expansive use of RICO. In the

Journal

’s pages, the government’s actions were likened to the “I don’t have to show you any stinkin’ badges” law of

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

or

The Terminator

(“Arnold Schwarzenegger couldn’t play a scarier role”). One editorialist gleefully quoted from the Justice Department’s 398-page RICO manual, which warns against “‘imaginative’ prosecutions under RICO” and its use as a “bargaining tool” for plea negotiations.

A former IRS commissioner was willing to testify on behalf of Princeton-Newport. This was a subtle issue because Congress had recently changed the tax law so that both sides of a hedged trade would be treated as short-term. The judge ruled that the former IRS commissioner’s views would confuse the jury and did not allow the commissioner to testify.

“I did not commit a crime,” Regan told the jury. “I did not cheat on my taxes, I’m totally 100 percent innocent.”

The prosecutors hammered on the petty subterfuge of the trades. Rather than openly buying back the securities all at once, at the same price, Princeton-Newport’s people broke up the transactions and varied the prices. They played the tapes for the jury. “Welcome to the world of sleaze” does not sound like a man proud of what he is doing.

On July 31, the jury convicted the defendants on sixty-three of the sixty-four counts, including racketeering. Regan was sentenced to six months in prison and fined $325,000. These penalties were lighter than what the prosecution had asked for. Andrew Tobias, writing in

Time

magazine, felt that “the judge seemed to be saying by his sentence that the U.S. Attorneys had gone a bit wild.” For his part, the judge said he intended to give Regan a three-month sentence but doubled it because he believed Regan had lied to the court.

Thorp put up a new dartboard in his Newport Beach office: a photo of Rudy Giuliani. “When half the leadership of your firm is convicted,” Thorp told

Business Week

, “it doesn’t help any.”

In March 1989, Michael Milken was indicted under RICO on racketeering and securities fraud charges. A year later, he admitted guilt on six felony charges, paid a $600 million fine, and was sentenced to ten years in prison. By that time, the junk bond market had collapsed, Drexel Burnham was in bankruptcy, and the 1980s were just about over. In June 1990 Martin Siegel got a mere two months’ sentence because of his cooperation. Boesky was released from his prison term in December 1989. After serving two years of a three-year sentence, he looked like a slightly sinister depiction of God himself, with patriarchal beard and shoulder-length gray hair.

Regan and the other Princeton-Newport defendants appealed their cases. All six convictions were overturned on appeal. None of the Princeton-Newport people served prison time. All had lost their jobs, and Regan had paid far more in legal fees (about $5 million) than the imposed, then overturned, fines.

The one person who came out relatively unscathed was Thorp. Yet his fortunes had been stunted by contingencies that his careful risk assessment had been unable to forestall. “The destruction of wealth was huge,” Thorp observed. The partnership employed about eighty people on two coasts. They managed $272 million. Together Thorp and Regan were collecting about $16 million a year in general-partner fees. Their own investments in the fund were compounding at an impressive rate.

Even these figures pale against what might have been. “There was an explosion in the hedge fund world shortly after” Princeton-Newport’s dissolution, “as far as money invested and size of opportunities,” Thorp explained. “We could have, I think, been running a five- or ten-billion-dollar hedge fund easily now.” There is some psychological truth to logarithmic utility. No one is so rich as not to fantasize about adding another zero onto net worth. Had Regan only stepped down, Thorp theorizes wistfully, “we’d be billionaires.”

E

XPANSIVE USE OF

RICO

makes strange bedfellows. In the lockup at Manhattan’s Metropolitan Correctional Center, “Fat Tony” Salerno ran into portfolio manager John Mulheren, head of another red-hot New Jersey investment firm, Jamie Securities. After hearing that Boesky had implicated him, Mulheren, who had stopped taking lithium for manic-depressive illness, packed guns in his car and went off with the stated intent of killing Boesky. Tipped off by Mulheren’s wife, sympathetic local police stopped Mulheren and took him into custody. He was charged with threatening a witness in a federal case. Giuliani’s office offered to overlook that if Mulheren would admit to stock parking and testify against others. Mulheren indignantly refused.

Mulheren and Salerno got along well. Mulheren had resumed taking his medication and had recovered his considerable charm. Salerno admired Mulheren’s refusal to testify against friends.

Just before Mulheren was transferred to a posh psychiatric institution in New Jersey, Salerno patted him on the back. “You’re all right,” Salerno said. “You’re the only guy on Wall Street who’s not a rat.”

“But I don’t know anything,” Mulheren insisted. “I don’t have anything bad to tell them.”

“Oh, yeah,” Salerno said, rolling his eyes.

“Right.”