Fortune's Formula (36 page)

Authors: William Poundstone

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Investments & Securities, #General, #Stocks, #Games, #Gambling, #History, #United States, #20th Century

T

HE

LTCM

DISASTER

was like a grisly highway accident. Arbitrage funds scaled down their leverage for a few seasons, then it was back to business as usual. One of the victims of the 1998 Russian default was another MIT-trained trader, John Koonmen. Koonmen worked in Lehman Brothers’ Tokyo office, trading convertible bonds for Lehman’s own account. He lost so much money that Lehman had to scale back bonuses for the entire Tokyo department. Koonmen was asked to leave the firm.

He acquired one souvenir of the panic that had done him in. It was a pool table formerly used in LTCM’s Tokyo office.

Koonmen was an expert backgammon player. Before coming to Tokyo, he haunted the illegal, big-money backgammon scene in New York. From the backgammon circuit, Koonmen knew John Bender, a gambler who managed the Amber Arbitrage Fund. Amber Arbitrage had a number of professional backgammon and poker players as investors. Its major investor was George Soros, through his Quantum Fund.

Bender was looking to get into the Japanese market. He hired Koonmen in 1999. Then, in spring 2000, Bender had a stroke. Koonmen began trading more aggressively. This violated one of the rules of the profession: The boss’s illness or vacation is not the time to try out exciting new approaches. Bender felt Koonmen was taking too much risk. By October, Bender had recuperated enough to close the fund and retire to a game preserve in Costa Rica. He and Koonmen spent the next few years squabbling over division of profits.

Koonmen meanwhile went to Amber Arbitrage’s investors and claimed credit for the fund’s recent performance. He persuaded many of them to roll their money over into a new fund that Koonmen was starting, Eifuku Master Trust.

One of the first things Koonmen had to explain to his investors was how to pronounce “Eifuku.” It was

ay-foo-koo

. Eifuku means “eternal luck.”

Soros invested in Eifuku. So did several high-net-worth Kuwaitis and UBS, a Swiss bank still smarting from the distinction of having been Long-Term Capital Management’s largest investor.

Like Meriwether, Koonmen believed that his management was worth a 25 percent cut of the profits. He also intended to rake in 2 percent of the fund’s assets each year, profitable or not.

Koonmen installed his LTCM pool table in Eifuku’s offices on the eleventh floor of the Kamiyacho MT Building. These lavish offices were the most extreme ostentation in Tokyo’s real estate market. Koonmen habitually wore black, often a black turtleneck with black pants. He drove around Tokyo in a metallic blue Aston Martin Vantage.

Eifuku Master Trust lost 24 percent of asset value in 2001. That misstep was forgotten as it posted a 76 percent gain in 2002. That was a terrible year for the stock market. Eifuku’s investors must have counted themselves lucky indeed.

In the first seven trading days of 2003, Eifuku lost 98 percent of those investors’ money.

As 2003 began, Koonmen had positions worth $1.4 billion backed by $155 million of asset value. That is about nine times leverage, less than LTCM had used. Unlike LTCM, Koonmen wasn’t even trying to diversify. His resources were committed to just three major trades. He had bought half a billion dollars’ worth of Nippon Telephone and Telegraph stock and sold short the same amount of its partly owned mobile phone subsidiary, NTT DoCoMo. A second trade involved long and short positions in four Japanese banks, with some short index futures as a hedge. Finally, Koonmen owned $150 million worth of the video game company Sega.

On January 6 and 7, the fund lost 15 percent of its value. It dropped another 15 percent on Wednesday the eighth. The bank that had extended Koonmen all this leverage was Goldman Sachs. They had the right to liquidate Koonmen’s positions to satisfy collateral requirements. Koonmen talked them into holding off a day.

Koonmen spent Thursday the ninth on the phone with investors. He was trying to talk them into putting more money into his dying fund. No one was interested. While this was going on, the fund lost another 16 percent of its value.

Friday the tenth was going into a three-day weekend in Japan. Goldman Sachs realized it wasn’t such a good idea to sell massive amounts of Sega and NTT before a long weekend. They held off until Tuesday. The fund shed 12 percent more in Friday’s trading.

On Tuesday, Goldman Sachs started unloading. The market in the securities Koonman held crumbled. Eifuku lost 40 percent of its value, shrinking to a mere 3 percent of where it started the year.

By Wednesday, that was down to 2 percent.

Koonmen was described as eerily emotionless during the carnage. When he came to write the “Dear Investor” letter, he assured his readers that he was doing everything to “preserve and maximize any remaining equity in the fund. There is however a strong possibility that there may not be any equity left at the end of the liquidation.” The letter concluded,

John Koonmen will try to contact each investor individually by phone in the next few days to further explain these unfortunate events and answer all direct questions. In particular, if any investors have questions concerning the logic and analysis behind the positions, John would be happy to answer these questions during those calls…This letter has been very hard to write. I am sure that it has been equally difficult for you to read. We will be in contact soon.

Koonmen closed the fund and went to Africa to photograph wildlife.

I

N HIS NOTES,

Claude Shannon recognized that the motives of a hedge fund manager are not necessarily congruent with those of the fund’s investors. In recognition of this fact, virtually all fund managers have their own wealth in their funds (they “eat their own cooking”). There are still incentives to assume risks that managers might not take with

just

their own money. It is now common to observe that a fund manager has a call option on fund investors’ wealth. The manager shares the upside but does not directly share the investors’ losses.

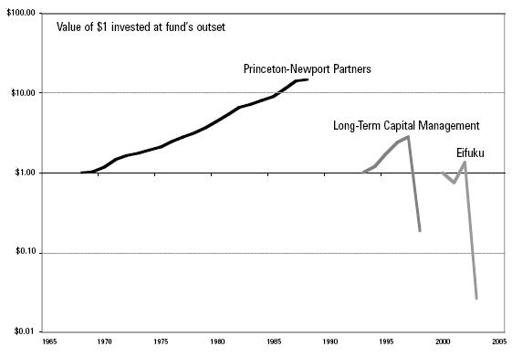

Hedge Fund Returns

Investors choose one fund over another on the strength of a few basis points of return. This creates the severest temptation for managers to boost return any way possible. One way to do that is to take “Russian roulette” risks that are likely to pay off in the short run, yet carry the possibility of disaster. Human nature and single-period financial models make it easy to blind oneself to long-term risk.

Risk management is a tough lesson to learn on the job. It can take years for ruinous overbetting to blow up in a trader’s face. When that happens, a career may be over.

There is much overlap between portfolio managers and serious gamblers. Whether this is good can be argued either way. William Ziemba believes that it is mostly good. Gambling provides the most important object lesson of all: going broke. There is no better way of demonstrating the need for money management than seeing your own money vanish while making positive-expectation bets. It is impossible to make the same point so viscerally with mere stochastic differential equations. As Fred Schwed, Jr., author of

Where Are the Customers’ Yachts?

, put it back in 1940, “Like all of life’s rich emotional experiences, the full flavor of losing important money cannot be conveyed by literature.”

I

N

1986

B

ARRON’S

ran an article ranking the recent performance of seventy-seven money managers. Claude Shannon, though not mentioned in the article, had done better than all but three of the pros. The

Barron’s

money managers were mostly firms with up to a hundred people. Shannon worked with his wife and a decrepit Apple II computer.

The August 11, 1986,

Barron’s

reported on the recent performance of 1,026 mutual funds. Shannon achieved a higher return than 1,025 of them.

When Warren Buffett bought Berkshire Hathaway in 1965, it was trading at $18 a share. By 1995 each share was worth $24,000. Over thirty years, that represents a return of 27 percent. From the late 1950s through 1986, Shannon’s return on his stock portfolio was about 28 percent.

Shannon had long thought of publishing something on his investment methods. Apparently his ideas, though profitable in practice, never met his standards of originality and precision. Shannon’s memory was starting to fail, too, making it unlikely he would ever complete such an article. In 1986 Philip Hershberg, an engineer turned investment adviser, interviewed the Shannons about their investing methods. Hershberg intended to publish an article, but this too never appeared. A draft of Hershberg’s article (supplied by Betty Shannon), along with Hershberg’s recollections, give the most complete view of how Shannon achieved these returns.

It had nothing to do with arbitrage. Shannon was a buy-and-hold fundamental investor.

“In a way, this is close to some of the work I have done relating to communication and extraction of signals from ‘noise,’” Shannon told Hershberg. He said that a smart investor should understand where he has an edge and invest only in those opportunities.

In the early 1960s, Shannon had played around with technical analysis. He had rejected such systems: “I think that the technicians who work so much with price charts, with ‘head and shoulders formations’ and ‘plunging necklines,’ are working with what I would call a very noisy reproduction of the important data.”

Shannon emphasized “what we can extrapolate about the growth of earnings in the next few years from our evaluation of the company management and the future demand for the company’s products…Stock prices will, in the long run, follow earnings growth.” He therefore paid little attention to price momentum or volatility. “The key data is, in my view, not how much the stock price has changed in the last few days or months, but how the earnings have changed in the past few years.” Shannon plotted company earnings on logarithmic graph paper and tried to draw a trend line into the future. Of course, he also tried to surmise what factors might cause the exponential trend to continue or sputter out.

The Shannons would visit start-up technology companies and talk with the people running them. Where possible, they made it a point to check out the products of companies selling to the public. When they were thinking of investing in Kentucky Fried Chicken, they bought the chicken and served it to friends to gauge their reactions. “If we try it and don’t like it,” Shannon said, “we simply won’t consider an investment in the firm.”

Shannon became a board member of Teledyne. He was not just a distinguished name in the annual report but was actively scouting potential acquisitions for CEO Henry Singleton. For instance, in 1978 Shannon investigated Perception Technology Corporation on behalf of Teledyne. Perception Technology was founded by an MIT physicist, Huseyin Yilmaz, whose training was largely in general relativity. During the visit with Shannon, Yilmaz spoke enthusiastically about physics, asserting that there was a “gap in Einstein’s equation” which Yilmaz had filled with an extra term. Yilmaz’s company, however, was involved in speech recognition. They had developed a secret “word spotter” that would allow intelligence agencies to automatically listen for key words like “missile” or “atomic” in tapped conversations. Another product allowed a computer to talk.

Shannon’s pithy report warned Singleton that speech synthesis “is a very difficult field. Bell Telephone Laboratories spent many years and much manpower at this with little result…I had a curious feeling that the corporation is somewhat schizoid between corporate profits and general relativity. Yilmaz, Brill and Ferber all impressed me as scientifically very sharp and highly motivated, but much less interested in product development, sales and earnings.” Shannon concluded: “I think that an acquisition of PTC by Teledyne would be meaningful only as a long-term gamble on scientific research. I would not recommend such an acquisition.”

Warren Buffett himself said that Singleton had the best operating and capital deployment record in American business. It is at least conceivable that Shannon’s judgments played a supporting role in that success.

Shannon was among the first investors to download stock prices. By 1981 he was subscribing to an early stock price service and downloading price quotes into a spreadsheet on his Apple II. The spreadsheet computed an annualized return.

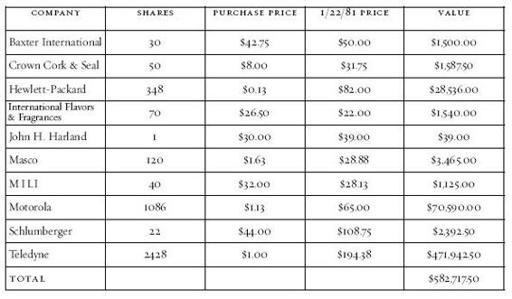

In a computer printout dated January 22, 1981, the Shannon portfolio ran:

This list may not be complete, as elsewhere Shannon spoke of owning at least one other stock (Datamarine) at this time. The portfolio value is a relatively modest $582,717.50. In 2004 dollars, that would qualify Shannon as the Millionaire Next Door. What is remarkable is the compound return.

The “purchase price” appears to be an average cost basis. Some of the stocks were acquired through mergers and/or purchases at various prices. The average appreciation of the Shannon portfolio at this point was about sixty-fold.

Shannon’s portfolio would have appalled Harry Markowitz (or any financial adviser). By this point, nearly 81 percent of the portfolio was in a single stock, Teledyne. The three largest holdings constituted 98 percent of the portfolio. “We have not, at any time in the past 30 years, attempted to balance our portfolio,” Shannon told Hershberg. “I would have liked to have done so were it not for tax considerations.” At age seventy, Shannon was fully invested in stocks. “I am willing to borrow on our investments if necessary,” Shannon vowed, “rather than sell our stocks and convert to interest-bearing instruments.”

Shannon told Hershberg that the

worst

-performing company he then owned was Datamarine International. He had bought it in 1971, and it had averaged only 13 percent(!) over that period. He planned to hold on to it as he liked its acquisition plans.

Shannon picked several winners that had nothing to do with digital technology. One was Masco, a company that makes building supplies. In the early 1980s, the Shannons bought stock in two companies that printed checks (John H. Harland and Deluxe). The stocks were reasonably priced, apparently because PCs had just become popular and everyone was abuzz about paperless transactions. Betty doubted that paper checks would become obsolete quite so soon. Both companies had good earnings growth. From 1981 to 1986, the compound return was 34 percent for Harland and 40 percent for Deluxe.

As to overall performance, Shannon told Hershberg,

We’ve been involved for about 35 years. The first few years served as a kind of learning period—we did considerable trading and made moderate profits. In switching to long-term holdings, our overall growth rate has been about 28% per year.

Shannon is apparently excluding the early learning period from the claimed 28 percent return. He did not say how or if he accounted for stocks he no longer owned. That can make a big difference in the return of an actively managed portfolio. However, the Shannons apparently never put too much money into a new stock, and they sold rarely after the mid-1960s. Practically all of the profit came from the Teledyne/Motorola/Hewlett-Packard triumvirate.

Shannon had bought Teledyne for 88 cents a share, adjusted for stock splits. Twenty-five years later, each share was worth about $300, a 25 percent annual return. Codex had cost Shannon 50 cents a share; by 1986 each share had become a share of Motorola worth $40, translating into a 20 percent return rate. Dividends, not included in these returns, would nudge up the figures.

Shannon’s best long-term investment was Harrison Labs/Hewlett-Packard. This achieved a 29 percent return over thirty-two years. In his initial purchase of Harrison Labs, Shannon paid the equivalent of 1.28 cents for what would become a $45 share of Hewlett-Packard by 1986. That’s over a 3,500-fold increase. The initial investment had doubled eleven times and then some. Shannon’s blackboard projection had come true: 211 = 2048.