Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream (23 page)

Read Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream Online

Authors: H. G. Bissinger

Tags: #State & Local, #Physical Education, #Permian High School (Odessa; Tex.) - Football, #Odessa, #Social Science, #Football - Social Aspects - Texas - Odessa, #Customs & Traditions, #Social Aspects, #Football, #Sports & Recreation, #General, #United States, #Sociology of Sports, #Sports Stories, #Southwest (AZ; NM; OK; TX), #Education, #Football Stories, #Texas, #History

THE MAJORETTES, THEIR BLACK-AND-WHITE COSTUMES FALLING

just below the buttocks, twirled and beckoned as the bandfifty-four clarinetists, fifty-one flutists, thirty-six cornetists,

twenty-six trombonists, twenty-five percussionists, eighteen saxophonists, fourteen French horn players, nine baritone players,

and nine tubaists-belted out "Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy." The

color guard waved its flags to "Barbara Ann." The master of

ceremonies made the introductions with the flare of a circus

ringmaster asking the audience to direct its attention please to

the center ring. "Ladies and gentlemen, the very best football

team in the state of "Texas!" From all around came whoops and

cheers for the two rows of players at the front in their black

jersies, from the stunningly dressed girls over in the corner

with their leather skirts and Vuitton bags and blond hair that

rose to a rounded peak and then fell like the fanned plumes

of a peacock, from the clean-cut boys in their pleated pants

and stone-washed jeans and short haircuts, from the teachers

dressed in black, from the parents who brought along toddler

sons in black football uniforms and toddler girls in cheerleader

outfits, from the rows of Pepettes in their white tea-party

gloves. The lights went off for a flashlight show, little rings of

light twirling around, once again like something from the circus. There was a skit in which the Panther mascot moved about

ripping up paper tombstones symbolizing Permian's fallen op ponents. The sports director of one of the local network affiliates came forward to give the Superstar of the Week award to

the Permian defense, and twelve of the boys in black jersies

coyly swaggered forth out of their metal chairs to accept it to

more wild applause and whistles. The lights dimmed and the

players went to find their Pepettes so they could put their arms

around them for the singing of the Permian alma mater. Up in

the bleachers the rest of the students locked hands.

The lights went back on. A couple of Pepettes stayed around

to take down the black and white streamers and black and white

balloons arching across one side of the bleachers to the other

like a covered bridge and the beautiful hand-crafted posters

ringing the walls. It was time to go to school, at least for some

students.

Understandably heady from the experience of the Friday

morning pep rally, lion Billingsley's focus was on the game

ahead, not on school. Not all the weekly pep rallies were as

rousing as this one had been, but it was always hard to concentrate after them. "I don't do much on Fridays," he said as he

sauntered off to class in his black jersey with the number 26 on

it, and even if he had felt otherwise about it, there wasn't a heck

of a lot to do anyway. School was just there for Don, a couple of

classes to fill up time that offered virtually no challenge whatever, and he was the first to admit that if he was learning anything his senior year it was a miracle.

His schedule that day included sociology class, in which he

watched a video of a Geraldo Rivera television special succinctly titled "Murder" while munching on fresh-baked cookies that he

had been given during the pep rally. As his class instruction

that day he listened to an interview with the noted criminal

theorist Charles Manson and heard relative-, of crime victims

make such intellectually stimulating comments as "I would like

to see him die in the electric chair. He doesn't deserve Lo live."

It included photography, with the class spending the period

learning how to feel comfortable in front of a television camera.

When it was his turn, Don dutifully rose to the challenge by

successfully mouthing the scripted words, "This is Don Billingsley. Headline news next ...

It included English, where the class spent the first ten minutes going over the homework assignment for Monday and the

next forty-five minutes doing the homework assignment for

Monday.

It included food science, this particular lesson being on Correct Menu Form and the question of what one should place first

on the menu when writing it out, shrimp cocktail or Jell-O

salad. "This is what I do all day," said Billingsley as he grappled

with the shrimp cocktail versus Jell-O issue, moments before

plunging into the far murkier ground of the appropriateness

of listing cream of tomato soup and grilled cheese sandwich on

the same line. "All I do in class is show up. They should make

these classes fifteen minutes long. Last year in English I had

to work. This year it's like, teach me something before I go to

college."

Not all classes were like this, but even in accelerated courses

the classroom at Permian was hardly a hotbed of intellectual

give-and-take. It was not uncommon for teachers at Permian to

teach for only a quarter or a third of the period and then basically let students do whatever they wanted as long as they did it

quietly. It was also unusual to find teachers who demanded

from students their very best, who refused to succumb to the

notion that there was no reason to challenge them because they

simply didn't care. When there was a novel approach in the

classroom, it was geared for a generation indisputably weaned on the fast foods of television and the VCR, not the written

word. To get students to learn history, one teacher played a

version of "Jeopardy." Another teacher in an honors English

course, instead of having the students read The Scarlet Letter one

year, showed them a video of it.

Many teachers felt that no matter how creative they were in

the classroom, it wouldn't make a difference anyway. They

talked about a devastating erosion in standards, how the students of today bore no resemblance to the students of even ten

or fifteen years ago, how their preoccupations were with anything but school. It was hard for teachers not to feel depressed

by the lack of rudimentary knowledge, like in the history class

in which students were asked to name the president after

John F. Kennedy. Several students meekly raised their hands

and proffered the name of Harry Truman. None gave the correct answer of Lyndon Johnson, who also happened to have

been a native Texan. .

In 1975, the average SAT score on the combined math and

verbal sections at Permian was 963. For the senior class of

1988-89, the average combined SXF score was 85 points

lower, 878. During the seventies, it had been normal for

Permian to have seven seniors qualify as National Merit semifinalists. In the 1988-89 school year the number dropped to

one, which the superintendent of schools, Hugh Hayes, acknowledged was inexcusable for a school the size of Permian

with a student body that was rooted in the middle class. (A year

later, with the help of $15,000 in consultant's fees to identify

those who might pass the required test, the number went up

to five.)

Some teachers ascribed the drop in academic performance to

the effects of court-ordered desegregation as well as a rapid

increase in the town's Hispanic population. In eight years

Permian had gone from being a virtually all-white school to one

where the proportion of minorities in the student body was

about 30 percent. In hush-hush tones, some teachers blamed

the school's woes on the "Mexicans," or on the blacks, even though the school still very much had the look and feel of a

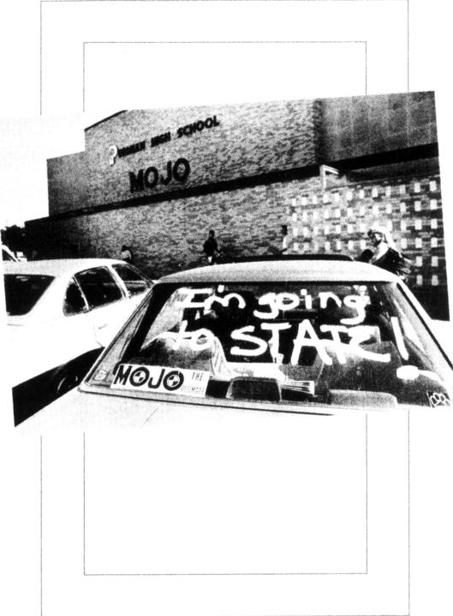

white suburban high school, its parking lot filled with new and

shiny cars, the majority of its students dressed in striking

outfits.

Some teachers blamed the erosion on the effects of the economic downturn in the oil patch, which had dealt Odessa a

crippling blow. Some blamed it on the breakdown of the family

unit; more and more kids were living with single parents who

had to work morning, noon, and night just to make ends meet

and didn't have the time or the inclination to promote the virtue of doing well in school. Some blamed it on parents who

seemed much less interested in pushing their kids in the classroom than in football or band or choir. Some blamed it on

themselves, acknowledging that the passion they had had for

teaching twenty years ago had run dry. Some blamed it on recent educational reforms passed in Texas that instead of making the classroom more stimulating, more creative, had done

just the opposite by turning the teacher into a glorified clerk

forced to follow an endless series of rules and procedures.

Despite the litany of possible reasons, it was hard not to wonder if the fundamental core of education-the ability of teachers to teach and the ability of kids to learn-had gotten lost. Its

problems didn't make Permian a bad school at all, just a very

typically American one.

"It still amazes me when I give a test in grammar and the kids

can do it," said English teacher Elodia Hilliard with more than

a touch of sadness in her voice. "It used to be the other way

around. I used to be surprised whenever they didn't know it.

Now I'm amazed when they do know it." When Hilliard looked

around the classroom she saw students with no direction, and

she wondered if they saw any point at all in being well read and

intelligent. She listened to parents who, rather than promising

to try to motivate their children, made excuses for them-the

homework was too hard, or the book they had been assigned

had too many cuss words in it. Even when she got them to read, the leap to conceptual, creative thinking seemed as far off as a

trip to Jupiter. It almost seemed to her and other teachers as if

students were scared of it.

There was a time when she had had unflappable faith in her

profession, when she had encouraged the best and brightest to

follow in her footsteps and spread the gospel of literature and

grammar with evangelical zeal. But not anymore. "I really felt

we made a difference," she said one clay in her classroom, devoid of' the usual corner shrine to Mojo but instead decorated

with lovely posters illustrating the meanings of hyperbole, oxymoron, metonymy, and personification. "Now I'm beginning to

wonder. I don't know. I'm really uncertain." She bent over

backward not to be negative, but she had a view of students she

could not suppress. "'they like to have cars. They like stereo

speakers that are fancy. They like to go skiing. They like to

wear good jewelry." In her mind, students seemed in search of

only one thing: "Having fun is what it's all about."

Jane Franks, who had been teaching for thirty-one years and

eagerly counted off the days until her retirement at the end of

the year, felt the same way. Today's students had become enigmas to her. They weren't disrespectful. They weren't obnoxious. They weren't demanding. It wasn't that they were good

kids, or had kids, or any kind of kid at all. That would have

been much better than what they were now, deadened to themselves and to the world around them.

""These kids don't take responsibility, or don't know how," she

said. "Kids used to worry about where they were going to fit

into the world. Kids today don't seem to worry if they are going

to fit in society, because they don't give a hoot.

"Twenty years ago I was working my kids to death, and now

I have to remind my seniors to use capital letters and put periods at the end of sentences.