Gallipoli (11 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

This is in spite of, and perhaps in part because of, the hardships they must suffer together: sleeping in stables, doing chores, eating poorly â on a diet that is little more than tough beef, old potatoes and endless bread and jam â being bellowed at, training till they drop. On their third night in the stables, the rain pours on them like an open tap, drenching all their bedding and scratchy army blankets with a flood that is ankle deep.

âAre we downhearted?' comes a jovial cry in the night.

âNo!' comes the bantering response from all around.

39

One bloke tells them that he was not sure whether to enlist or not, and so, on his way to church with his best girl, he'd asked her what her favourite hymn was, knowing it would be one of two. âIf she had said “Abide with Me”,' he tells his new mates, âI would not have volunteered, but she promptly said “Onward, Christian Soldiers”.'

40

And so, here he is!

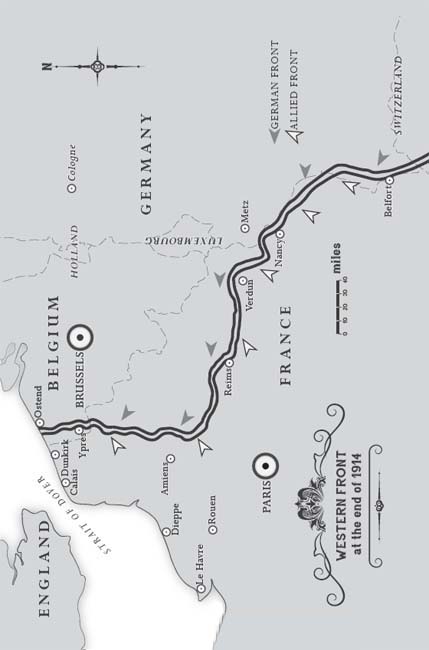

MIDâLATE SEPTEMBER 1914, WESTERN FRONT, FRANCE, âYOU CAN BEND, BUT YOU CANNOT BREAK'

This is warfare as never before seen in history. Yes, there have previously been massive armies, and artillery, and machine-guns, but never on this scale nor with this much

firepower

.

After that first day of crossing into Belgium,

die deutsche Armee

, the Imperial German Army, had barely been stopped, with Brussels falling on 20 August, followed by Luxembourg and the Ardennes.

The Battle of the Marne had begun in early September as five German armies totalling one and a half million men fought all the way to that tributary of the Seine that is the River Marne, threatening to engulf Paris, just 43 miles away. Against them, five French armies and the British Expeditionary Force under Field Marshal Sir John French had fought themselves to a complete standstill, suffering casualties on a horrific scale, with over 80,000 soldiers killed in the first week, making it 155,000 French dead for the first five weeks of the war. The fate of the whole battle had been teetering on the edge, when the cavalry had arrived in unlikely form.

Soldiers of the French reserve, 6000 strong, had turned up at the front in Parisian taxicabs â ever after to be known as

les taxis de la Marne

â helping the Allies to consolidate an unlikely breakthrough that had been made in a gap between Germany's First and Second Armies. For the first time, the Germans had fallen back to consolidate their own position.

Now, with two hugely powerful forces facing each other along a front that is 350 miles wide, and already 150,000 French, British and Germans dead

in just eight days

of the Battle of the Marne, there proves to be only one way to survive. It is John French who is among the first to realise it, during the First Battle of the Aisne, on 14 September, shortly after Germany's new artillery shells â what the men call âJack Johnsons'

41

â begin to fall on his soldiers. Fired from six-inch howitzers, the high-explosive black shells are far more devastating than anything the British have seen, and in open country under bombardment, the solution becomes clear.

Dig

.

Dig. Dig. And then dig some more!

âThroughout the whole course of the battle our troops have suffered very heavily from this fire,' French would report, âalthough its effect latterly was largely mitigated by more efficient and thorough entrenching, the necessity for which I impressed strongly upon Army Corps Commanders.'

42

And, of course, as the British bring their own heavy artillery and machine-guns forward, the Germans do the same â always choosing to build their trenches before open ground, where an advancing force will be most exposed and âthe much greater relative power which modern weapons have given to the defence'

43

can simply cut them to pieces, with machine-guns capable of firing nine bullets

a second

.

With those bullets and shrapnel filling the air like a swarm of angry bees, making both advancing

and

retreating now out of the question, there is only one way to go, and that is down. If you don't get beneath ground level as a live man, you will soon be there as a dead man, and both sides dig demonically. And once you have dug deep, the next thing to do is dig

wide

, to try to dig around the flank of your enemy and attack from there, âin order to escape the costly expedient of a frontal attack against heavily fortified positions'.

44

The Allies dig towards the German right flank, while the Germans furiously dig towards the Allied left flank. Of course, all kinds of military manoeuvres are tried to break this nexus but, again, Sir John French notices, âall ended in the same trench! trench! trench!'.

45

âThe Race to the Sea', by Jane Macaulay

He establishes a military maxim that will never leave him: âGiven forces fairly equally matched, you can “bend” but you cannot “break” your enemy's trench line.'

46

And so begins the famed âRace to the Sea', the parallel lines of trenches anywhere from a mile to 50 yards apart that will eventually extend from Alsace, at the Swiss frontier with France, to the North Sea, separated by a no-man's-land that continues to kill the vast majority of those who venture into it.

In only a matter of weeks, this entirely new kind of battle â âtrench warfare', it is called â takes hold. The old tenets of speed, outflanking and

attack

, of charging cavalry and precisely executed wheeling movements, have been quickly replaced by depth, consolidation and

defence

, interspersed with regular mad charges from both sides, as thousands of men with death-stares as fixed as their bayonets charge to their all but certain deaths, into the teeth of heavily entrenched, chattering enemy machine-guns, backed by heavy artillery, flanked by reams of barbed wire and manned by tens of thousands of soldiers.

Who can possibly win at this type of warfare? No one. But the side that first runs out of soldiers to be killed loses.

21 SEPTEMBER 1914, IN THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN, BACK DOWN OFF THE SHELF

For all the downsides of war, the undoubted upside is that promotional opportunities are available for survivors as they never are in peacetime. For, in the furnace of

actual

warfare instead of mere training, there are demonstrations of competence and incompetence, bravery and cowardice â not to mention sheer, brutal attrition â which mean that those on the lower rungs can suddenly rise to dizzying heights that they might never have otherwise dreamed of.

A case in point is Vice-Admiral Sackville Carden, now in charge as the Admiral Superintendent of the Malta docks â âthe final pre-retirement posting of an average undistinguished career',

47

as one writer puts it â when he receives an extraordinary cable, ordering him to take the reins of the British East Mediterranean Squadron, charged among other things with ensuring that the German ships the

Goeben

and

Breslau

don't escape from the Dardanelles.

It is a reluctant appointment of the Admiralty's, with Churchill himself soon to write of Carden to the First Sea Lord Sir John Fisher, the civil head of the Admiralty, âhe has never commanded a cruiser Sqn. & I am not aware of anything that he has ever done which is in any way remarkable'.

48

The curmudgeonly 73-year-old Fisher, who has just returned to the post of running the Admiralty â a post he had previously held from 1904 to 1910 â finds himself in a moment of rare agreement with the young and flighty Churchill, who tends to drive him mad with his brilliance and his cavalier approach to the fleet. âWho expected Carden to be in command of a big fleet?' Fisher writes to a colleague. âHe was made Admiral Superintendent at Malta to shelve him.'

49

But there is no choice, and Carden it is. Never has he had a responsibility like this, but all he can do is answer his country's call and do the best he can.

LATE SEPTEMBER 1914, AUSTRALIA, THE BEAT GOES ON

For all the joy of such actions as the taking of Rabaul and other German possessions in the Pacific, the truth of it is that they are no more than minor skirmishes, whereas what Britain really expects from her loyal sons in Australia is thousands of men, hopefully

tens

of thousands, ready to shoulder arms and come to the Mother Country's aid in the theatres of war in which Great Britain herself is engaged.

And they are not long in coming. From farms, foundries and factories, from shops and shoemakers, from settlements, towns and villages all over Australia, the young men continue to flood into recruitment depots, and from there to the training camps, where they are poked, prodded, hustled, bustled, shorn, shouted at and ordered about as soldiers have been since time immemorial when the horizon of the near future shows black battle clouds approaching.

There are so many that Lord Kitchener himself has passed on to the High Commissioner in London, Sir George Reid â who has passed it on to the Australian press â his âspecial thanks for the splendid help promised by Australia, and hopes and believes that everything will be done promptly and well. He highly appreciates the way in which his scheme has been carried out. He knows the Australian soldier, and knows that he will give a good account of himself. His final words were, “Roll up, roll up.”'

50

At the Rosebery Camp, Trooper Bluegum is in it with the best of them â all of it on foot, despite having joined the mighty Light Horse. As their horses are not yet ready, they drill day after day to master âthe mysteries of sections right, form troop, form squadron, form column', before spending whole days learning how to do rifle drill, to âstand at ease', âstand at attention', âslope arms', âpresent arms' and all the rest till their arms ache. And all this before they are even allowed to âfix bayonets' and practise sticking those bayonets into dozens of âGermans', who in fact look a lot like suspended bags of straw.

51

25 SEPTEMBER 1914, DAMN

EMDEN

!

For those contemplating the despatch of 30,000 soldiers across the seas to England, the situation is tense. Two German armoured cruisers,

Gneisenau

and

Scharnhorst

, had been reported in the freshly

former

German colony of Samoa on 14 September, just 1800 miles from Auckland. They are currently âat large and unlocated'.

52

Meanwhile, in the Indian Ocean,

Emden

, under the command of Kapitän Karl von Müller, has been continuing to send British merchant ships to the bottom at much the same rate of knots as they had previously been happily proceeding along the trade routes. Three days earlier, on the evening of 22 September,

Emden

had made an audacious raid on the harbour of Madras, firing its ten guns on the town and its oil refineries, creating complete havoc and sowing panic before just as quickly making good its escape, with barely a shot fired back at it.

Unleashed in the Bay of Bengal, as reported in the Australian papers, the German cruiser had captured six British ships, âof which five were sunk, and the sixth sent into Calcutta with the crews'.

53

(Von Müller's treatment of captured crews, it is grudgingly accepted, has been nothing short of gentlemanly â something amazing to find in a modern German man of war, commanding a modern German man-o'-war.) True,

The Sydney Morning Herald

reports to its readers that the head-lined MARAUDING EMDEN

54

is dangerous and strong, âbut not so strong as the

Sydney

and

Melbourne

',

55

and yet the authorities do not care to take that chance.

If that German cruiser got among insufficiently protected troopships preparing to take the New Zealanders and Australians across the Indian Ocean, the results could be catastrophic.

As a first precaution, on 25 September,

Minotaur

from Britain and

Ibuki

from Japan, which will be escorting the troopships across the Indian Ocean, are directed to continue to travel east across the bottom of Australia after they reach Albany (expected around 1 October) to gather in the New Zealand troopships and take them back to Albany.

Melbourne

, meanwhile, is despatched to chaperone the recently departed Queensland troopships into Port Phillip Bay. Here they will harbour until being given the go-ahead to head off west once more, across the Great Australian Bight, to âthe point of concentration' off Albany.

56

26 SEPTEMBER 1914, THE MOUTH OF THE DARDANELLES BARES ITS TEETH