Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (12 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

A surviving menu from the first breakfast served in the first-class dining saloon reveals a wide selection of hearty British favorites—grilled mutton kidneys and bacon, lamb collops, Findon haddock and fresh herrings [sic]—with some nods to the American palate in the offerings of Quaker Oats, boiled hominy, buckwheat cakes, and corn bread. Both W. T. Stead and his American table companion, a New York lawyer named Frederic Seward, would therefore have had no trouble selecting familiar breakfast fare from the menu card. The two men bonded early in the voyage, and the fact that they were both minister’s sons likely provided some common ground for table talk. Stead’s upbringing as the son of a Congregationalist preacher in a small Yorkshire town was the matrix for much of his reformist zeal. As a young boy, he had once expressed indignation at an injustice by exclaiming, “

I wish that God would give me a big whip that I could go round the world and whip the wicked out of it!” In later years Stead’s father would inquire wryly, “Aren’t you going to leave a little for the Lord Himself to do, William?”

With cards and letters left to write, Stead would not have lingered long over breakfast. Francis Browne, too, soon left the table he shared with the Odell family to go back up on deck for more photographs. A shot he took from the aft end of A deck shows the arc of the

Titanic

’s wake through the water as the ship took a twisting path in order to test her compasses. Browne would label another photograph on the same album page “The Children’s Playground” since it shows six-year-old Douglas Spedden spinning a top beside a cargo crane on A deck, while his father, Frederic, looks on.

Frederic Spedden and his wife, Margaretta, known as “Daisy,” were both heirs to Gilded Age fortunes and divided their time between their home in Tuxedo Park, a fashionable enclave north of New York City, and a summer “camp” near Bar Harbor, Maine. In the winter the couple boarded the liners for warmer climes, and this year’s itinerary had included stops in Algiers, Monte Carlo, Cannes, and Paris. The Speddens were devoted to their only child, Douglas, and a nursemaid, Elizabeth Margaret Burns (nicknamed “Muddie Boons” by Douglas), was traveling with the family along with Daisy’s maid. Daisy dabbled in writing and kept a diary in which she had written after boarding the

Titanic

in Cherbourg: “

She is a magnificent ship in every way and most luxuriously, yet not too elaborately, outfitted.”

In his enthusiastic shooting that morning, Francis Browne made two double exposures that would have been discarded had they not proven to be of such historical significance. One photo showing an unidentified couple taking a stroll on A deck is overlaid with a ghostly view inside the private promenade deck of Charlotte Cardeza’s deluxe suite where a “Bon Voyage” bouquet of flowers can be seen standing on a wicker table. The second is of even more significance because it is the only photograph taken inside the

Titanic

’s wireless cabin, or Marconi Room as it was known. Browne snapped two shots in one exposure of the junior Marconi operator Harold Bride sitting at the telegraph key wearing his headphones. Curving downward on the wall in front of him are two brass pneumatic tubes that brought passenger messages up from the Enquiry Office three decks below. For a charge of twelve shillings and sixpence ($3), passengers could leave a message of up to ten words with a charge of ninepence (35 cents) for each additional word. The message was then placed in a cylinder and sent up to the Marconi Room where it dropped out the bell-shaped end of the pneumatic tube into a wire basket.

While Browne continued snapping photographs that morning, Captain Smith made his inspection tour of the ship accompanied by his senior officers. Each day at 10:30 a.m. Smith took a walk through all decks of the ship, including the public rooms in all three classes, the dining saloons and galleys, the hospital, workshops, and storage areas, until he finally reached the engine rooms, where he was greeted by the chief engineer. On this first morning at sea, there had been an emergency drill with the sounding of alarm bells and the closing of the steel doors that sealed off the liner’s sixteen watertight compartments. An assistant electrician named Albert Ervine described this rehearsal in his last letter to his mother, and concluded: “

So you see it would be impossible for the ship to be sunk in collision with another.”

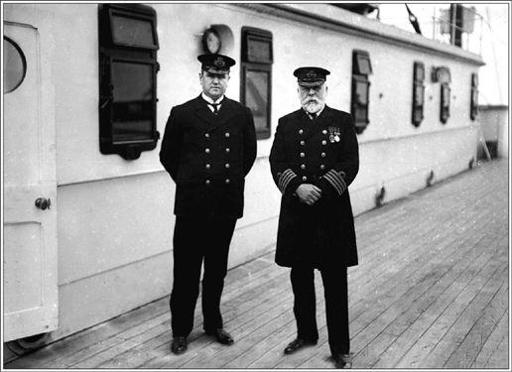

Captain Smith (at right) with Purser McElroy

(photo credit 1.26)

Following his daily inspection, Smith returned to the bridge and reviewed with his officers any matters arising from the tour and also checked on the ship’s progress, looking over the charts and reading any radio messages sent forward by the Marconi Room. The captain was likely aware that some tension existed among his senior officers, stirred up by his last-minute installation of Henry Wilde as chief officer. This change had caused William Murdoch to be bumped down from chief to first officer while Charles Lightoller was demoted to second officer, and the previous second officer had left the ship in Southampton. According to Lightoller,

the ruling lights of the White Star Line thought it would be a good plan to send the Chief Officer at the

Olympic

, just for the one voyage, as Chief Officer of the

Titanic

, to help, with his experience of her sister ship. This doubtful policy threw both Murdoch and me out of our stride; and, apart from the disappointment of having to step back in our rank, caused quite a little confusion.

One consequence of this change was the missing binoculars for the lookouts. On the trip to Southampton from Belfast, the lookouts had used the now-departed second officer’s binoculars, which he had locked in a drawer in his cabin before he left the ship. When Lightoller inquired about binoculars for the lookouts, he was told that none were available for them.

Lightoller assigned the responsibility for the last-minute officer shuffle to head office rather than to Captain Smith since he remained unfailingly loyal to “E.J.” and believed that any man ought to have beeen willing to “give his ears” to sail under him. With his white beard, immaculate uniform, and soft-spoken manner, Captain Edward J. Smith was also a favorite with the passengers, and many frequent travelers would plan their crossings to sail with him. His thirty-eight years of service with the White Star Line had earned him the title of Commodore of the White Star Fleet and the honor of commanding new ships on their maiden voyages.

On this particular morning, Captain Smith likely timed his inspection tour to be back on the bridge to greet the Queenstown harbor pilot, John Whelan, who was well known to Smith and had guided the

Olympic

during its maiden stop in Queenstown the year before. Whelan had spent the night in the pilot’s signal tower onshore and, upon sighting the liner flying a red-and-white signal flag indicating that his services were wanted, had climbed into a small whaling boat and been rowed out to the ship.

As Francis Browne watched the approach of the pilot’s boat from up on deck, someone standing nearby asked him, “

What fort is that?” pointing to a massive structure on the west side of the harbor entrance.

“Templebreedy, one of the strongest in the kingdom” was Browne’s reply. Cork Harbor, a magnificent natural harbor, had long been an important British naval base, and the ruins of older fortifications dotted the hills around it. Templebreedy was a new fortress, completed only three years before, and giant modern guns bristled in its battery.

“And do Redmond and his Gang want to take that place?” another voice asked.

“And why do you call them a ‘Gang,’ Sir?” a third person challenged.

John Redmond was an Irish Member of Parliament and a longtime campaigner for home rule, a form of self-governance for Ireland within the United Kingdom. The issue was highly topical as the Third Home Rule Bill supported by Redmond and his party was receiving its first reading in the British House of Commons that very day. And this time it looked as if home rule for Ireland might become a reality. Francis Browne, however, refrained from being drawn into a political discussion, since, with Cork Harbor in view, it was time for him to take his last luncheon on board. He carried his camera to lunch with him, and took the only surviving photograph of the

Titanic

’s first-class dining saloon in service. It is another less-than-perfect photograph, but in spite of its flaws it gives an intimate view of passengers sitting at tables set with white linen, silver, and upright menu cards, beneath the room’s elaborately plastered ceiling.

While Frank Browne and the Odells had lunch, two tenders, the

Ireland

and the

America

, departed from the White Star jetty in Queenstown. The

Ireland

was the first to leave, carrying ten first- and second-class passengers along with some newspapermen going out for a look at the new liner. The tender steamed over to a quay a few hundred yards away to pick up 1,385 sacks of mail to be carried to New York. (The ship’s mail service had earned it the designation RMS for Royal Mail Steamer.) Only three first-class passengers boarded at Queenstown: William Minahan, an Irish-American doctor from Fond-du-Lac, Wisconsin; his wife, Lillian; and his sister, Daisy. The Minahans had been visiting relatives in the “auld sod,” and William had sent a postcard from Killarney to friends in Wisconsin, saying “

It’s a good place to come from but U.S.A is a better place to live.”

The tender

America

followed slightly later, having been delayed by the late arrival of the train from Cork. It was heavily loaded with 113 third-class passengers, most of them Irish emigrants seeking a new life in the place for which their tender was named. Twenty-one-year-old Daniel Buckley, a farm laborer from Kingwilliamstown in County Cork, led a group of six friends, two of them teenaged girls aiming to become parlor maids. From County Mayo there was a similar group of fifteen, headed for Chicago. The night before they left home, dozens of their friends in Castlebar, County Mayo, had given them what was known as a “

live-wake” with fiddle music and dancing. During the half-hour trip out of the harbor, a twenty-nine-year-old weaver from Athlone named Eugene Daly raised the spirits of all by playing his bagpipes, known as

uilleann

, or elbow pipes. One song that was greeted with applause was the nationalist anthem “A Nation Once Again,” and many mouthed the words to the rousing chorus: “

A Nation once again! A Nation once again,/And Ireland, long a province, be/A Nation once again.” With the news about the Home Rule Bill filling the newspapers that morning, the song seemed particularly timely.

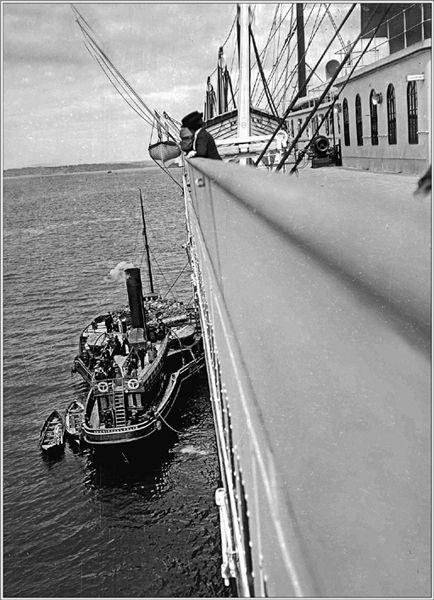

As the tenders drew alongside the

Titanic

, passengers already on board crowded the decks to watch them being unloaded. Second-class passenger Lawrence Beesley, a thirty-four-year-old English schoolteacher making his first Atlantic crossing, wrote that “

nothing could have given us a better idea of the length and bulk of the

Titanic

than to stand as far astern as possible and look over the side from the top deck, forwards and downwards to where the tenders rolled at her bows, the merest cockle-shells beside the majestic vessel that rose deck after deck above them.” A number of “bumboat” vendors hawking Irish linen, lace, and other souvenirs had also come out with the tenders. This was a popular feature of any stop at Queenstown and many passengers were eagerly waiting to view their wares. John Jacob Astor was seen haggling with a shawl-clad woman before pulling out a wad of U.S. bills to purchase a lace jacket for Madeleine. Up on the boat deck a small incident occurred when a stoker with a coal-blackened face poked his head up through the fourth funnel. Shrieks were heard from several startled women who hadn’t realized that this funnel was a dummy, used only for ventilation shafts from the galleys. The stoker had simply climbed up an interior ladder, likely to get a breath of fresh Irish air, but this innocent occurrence would later be recalled as yet another “ill omen” for the maiden voyage.