Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (11 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

But Stead himself was soon to become a victim of “Stead’s Law.” One of the most sensational stories in the “Maiden Tribute” series was entitled “A Child of Thirteen Bought for £5.” It described how a Cockney girl named “Lily” had been purchased from her drunken mother, taken to a midwife to attest to her virginity, and then to a brothel where she was put to sleep with chloroform. As the story ends, Lily is awakened when her “purchaser” enters the room. “

There’s a man in the room!” she screams. “Take me home; oh, take me home!” What the article neglected to mention was that Lily’s abduction had been engineered as a test case by Stead. He was the man who had entered the room posing as her “purchaser,” after which the girl had been spirited off to France in the care of Bramwell Booth, the head of the Salvation Army.

Rival newspapers began to dig into the story and soon Stead’s enemies saw their chance. On September 2, 1885, he and those who had assisted him in “buying” the child were arraigned in court on charges of abduction and procurement. Stead defended himself ably but was convicted on a technicality—that he had not secured the permission of the girl’s father. The judge’s hostility to Stead was evident throughout the trial and his instructions to the jurors left them with little choice except conviction. The judge even told the jury that they should not be prejudiced “

because in the streets some months ago were circulated … an amount of disgusting and filthy articles.” Yet it was Stead’s shattering of the language taboo that was perhaps the “Maiden Tribute’s” greatest achievement. What had formerly been “disgusting and filthy” could now be written about openly, allowing a widely ignorant public to glean useful information on sexual matters.

On November 10, 1885, Stead began a prison sentence of two months and one week. On every November 10 after his release, he would don his prison uniform and proudly walk about the streets. Yet “Stead’s Law” would have wider-reaching consequences than the newsman himself had ever imagined. During the debate on the CLA Act in the House of Commons, a Liberal member named Henry Labouchère had questioned why sexual acts between men should not be included in the bill. The late addition of the Labouchère Amendment made any act of “gross indecency” between men punishable by two years in prison—thus criminalizing homosexuality in Great Britain for the next seventy-two years.

Ten years after the passing of the CLA Act, the poet and playwright Oscar Wilde launched a libel suit against the brutish Marquess of Queensberry for a note he had left at Wilde’s club calling him “

a posing somdomite [

sic

].” Queensberry was the father of Wilde’s lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, and he had been stalking and harassing the playwright for months. When Wilde lost the case, he was charged and convicted of “gross indecency” and sent to prison for the two years of hard labor that the law required. W. T. Stead assailed the hypocrisy of Wilde’s conviction, noting that “

if all persons guilty of Oscar Wilde’s offences were to be clapped into gaol [jail], there would be a very surprising exodus from Eton and Harrow, Rugby and Winchester [elite schools], to Pentonville and Holloway [prisons].”

The harshness of prison life contributed to Wilde’s early death in 1900 at the age of forty-six. Stead never reflected in print on the connection between “The Maiden Tribute” and Wilde’s fate. However, after reading

De Profundis

, the book Wilde wrote while in prison, he sent a letter to the playwright’s friend Robbie Ross in 1904, saying:

I am glad to remember when reading these profoundly touching pages, that he [Wilde] always knew that I, at least, had never joined the herd of his assailants. I had the sad pleasure of meeting him by chance afterwards in Paris and greeted him as an old friend. We had a few minutes talk and then parted, to meet no more, on this planet, at least.

AS THE DEADLINE

for mail to be dropped at Queenstown approached on the morning of April 11, 1912, Millet and Stead would either have summoned a steward or joined the other passengers walking toward the Enquiry Office on C deck with letters and postcards. From there, the mail went down four decks to the post office, where it was sorted and put into canvas mailbags, each of which contained about two thousand letters. An electric hoist then moved the bags to the mail storage room one deck below in preparation for loading onto the Queenstown tenders. Many of these letters were not received till after the

Titanic

had gone down, and a good number were the last communication ever received from those who would not live to see New York. One of these is a letter from the

Titanic

’s chief officer, Henry Wilde, to his sister, in which he says: “

I still don’t like this ship, I have a queer feeling about it.”

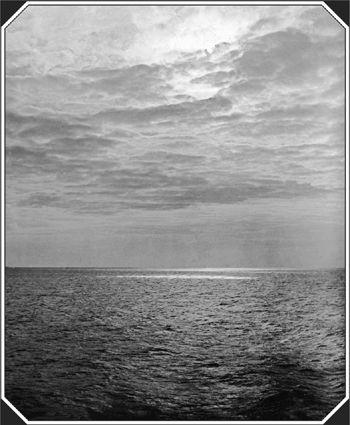

Francis Browne was up early on the morning of April 11 to capture the

Titanic

’s first sunrise on film.

(photo credit 1.14)

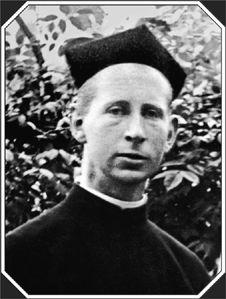

N

orris Williams awoke on Thursday morning to find his father standing by their cabin’s porthole looking out at the sun shining brightly on a calm ocean. By then Francis Browne was already up on the boat deck with his camera in hand. At sunrise he had taken a photograph of the sun breaking through the clouds. As an aspiring Jesuit, Browne probably also chose to make his morning meditation on deck at that hour. Certainly, he was eager to fit as much as he could into his last morning on the liner.

At approximately the time that Browne would have returned to his A-deck room before breakfast, a steward was carrying a tray to A-36, the starboard-side cabin opposite Browne’s. Each morning at seven o’clock steward Henry Etches brought tea and fruit to the

Titanic

’s chief designer, Thomas Andrews, whom he found always hard at work with plans and drawings spread out over the cabin. Though only thirty-nine, Andrews was already a managing director of Harland and Wolff, and it was his custom to travel on maiden voyages to observe a new liner in service and recommend improvements. He was also in charge of a nine-man “guarantee group” from Harland and Wolff that was on board to assist with any matters requiring special attention. On the rolled-up blueprints beside Andrews’s bed, there were sketched-in plans for shrinking the size of the underused reading and writing room to make way for additional staterooms. The papers that covered his desk and night table included notes on everything from reducing the number of screws in the stateroom hat hooks to staining the wicker furniture on one side of the ship a particular shade of green.

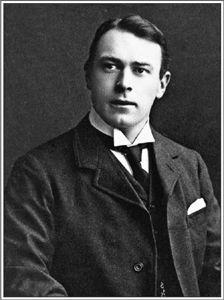

Andrews was a nephew of Lord Pirrie, Harland and Wolff’s chairman, but there was never a whisper that nepotism had boosted his career.

Thomas Andrews

(photo credit 1.85)

He had joined the firm as an apprentice at the age of sixteen and had worked tirelessly in virtually every department since then, often arriving for work at 4 a.m. He took special pride in this particular ship and had taken his wife and one-year-old daughter to admire the

Titanic

before she left for Southampton. Andrews was universally popular at Harland and Wolff—his coworkers described him as being “

sunny and big hearted” with “a wonderful, ringing laugh.” His wife Helen recalled being with him near the shipbuilder’s Queen’s Island works one evening when a long line of workers filed past. “

There go my pals, Nellie,” he had said to her, adding later, “and they are real pals, too.” Stewardess Violet Jessop remembered that, before sailing, the stewards had given a gift and a vote of thanks to “Tommy” Andrews for the improvements he had made to their “glory holes,” the tiny stewards’ quarters on the lower decks. “

Our esteem for him,” Jessop wrote, “already high, knew no bounds.”

Downstairs, in the first-class dining saloon that morning, many of those same stewards were already hard at work bringing breakfast to their assigned tables. Saloon steward Jack Stagg wrote to his wife that so far there had been “

nothing but work all day long” even though with a mere “317 first” on board he might end up with only one or two tables to look after. “Still one must not grumble,” he added, “for there will be plenty without any.” (No tables meant no tips, an important supplement to a steward’s wages.) Lighter duties may have suited steward William Ryerson who was new to White Star procedures since all his previous jobs had been on Cunard ships. Steward Ryerson was unaware that he shared a family connection with the posh Ryersons up on B deck. He was, in fact, a third cousin once removed to Arthur Ryerson, who was returning home for the funeral of his eldest son.

The thirty-two-year-old Steward Ryerson had been raised in Port Dover, Ontario, a village on Lake Erie, but had left as a teenager to join the British Army, where he saw service in India before returning to London. There he married an English girl and, with jobs being scarce, had signed on as a steward with Cunard. His wealthy distant relative, by contrast, was the son of Joseph T. Ryerson, who had founded a Chicago steel company. Arthur Ryerson had practiced law in Chicago before retiring to a mansion in Haverford, Pennsylvania, and a summer estate overlooking Lake Otsego near Cooperstown, New York.